The Precarious State of Higher Education in India and the Need for Intervention

The landscape of higher education in India is marked by significant disparities, particularly concerning representation across different social strata. A macro view reveals that only about 28% of students reach the higher education level across all types of institutions, including technical education. Within this segment, the dominance of the so-called General Category (GC), often associated with forward or dominant castes, is pronounced. Statistics derived from the current structure indicate that roughly 40% of students accessing higher education belong to this category, despite their relative numerical strength in the general population. Conversely, the remaining 59% to 60% are distributed among Other Backward Classes (OBC), Scheduled Castes (SC), and Scheduled Tribes (ST). We will discuss UGC 2026 guidelines in this article.

- A Victory Born of Sacrifice

- Dominance in Student Intake and Faculty Positions

- The Genesis of UGC's Equity Regulations 2026

- The Unprecedented Backlash from Dominant Sections

- Key Features of the UGC Equity Guidelines 2026

- Institutional Mechanisms for Equity Enforcement

- The Historical Context: Failures of Past Guidelines

- The Political Economy of Resistance and Compliance

- Addressing the Criticisms from the Dominant Narrative

- The Unfinished Struggle: Why the 2026 Regulations Still Fall Short

- Conclusion: The Significance of Enforceable Equity

- What you can do?

A Victory Born of Sacrifice

It is crucial to emphasize that the introduction of the UGC Equity Guidelines 2026 is not a mere administrative update; it is a hard-won victory achieved after the immense sacrifice of countless marginalized students who faced systemic exclusion. This progress belongs to them. However, a stark contrast in civic responsibility has emerged: Our educated people didn’t oppose EWS, yet their “uneducated” people are opposing the UGC 2026 guidelines. That is the fundamental difference in our social fabric. We must ask everyone to stand in support of these protections against those trying to derail them.

Dominance in Student Intake and Faculty Positions

This numerical imbalance in student admission only paints part of the picture. A critical examination of the academic and administrative leadership within these institutions—colleges, universities, and Higher Education Institutes (HEIs)—reveals an even more entrenched hierarchy. Data suggests that professors, deans, assistant professors, and chancellors are disproportionately drawn from the dominant social groups, often constituting 60% to 70% or more of the faculty and leadership positions.

This overwhelming presence creates an environment where the deep-rooted malaise of casteism is not only prevalent but subtly perpetuated within the very structures meant for meritocratic advancement. This entrenched presence of caste bias, subtle as it may be, has devastating consequences, reportedly leading to situations where meritorious students from marginalized backgrounds face immense pressure, sometimes tragically resulting in the loss of life. Can an institution truly foster merit when its very foundation is built on exclusion?

The Genesis of UGC’s Equity Regulations 2026

To directly address this systemic issue—the virus of casteism gripping the Indian educational ecosystem, especially in higher learning—the University Grants Commission (UGC) has introduced new guidelines. These regulations are officially titled the “Promotion of Equity in Higher Education Institutes Regulation, 2026.” These regulations fundamentally aim to establish equality and embed principles of inclusion and equity, concepts deeply enshrined in the constitutional ideals of the nation, within HEIs. The Gazette notification, issued on January 13th, formally passed these regulations, signaling a decisive move against entrenched caste-based discrimination.

The Unprecedented Backlash from Dominant Sections

Almost immediately following the issuance of these guidelines, a massive, coordinated campaign of opposition surfaced, primarily orchestrated by the dominant social segments who perceive themselves as having a historical claim to special privileges. This resistance stems from what appears to be a deeply ingrained habit of enjoying privileges accumulated over millennia. When initiatives promoting genuine equality are introduced, these groups interpret it as an attack on their entitlements, viewing equality itself as injustice.

The methods of opposition have been particularly noteworthy and often extreme, flooding social media platforms with exaggerated claims. Narratives suggest that members of the dominant castes will face imprisonment under the new stringent rules or that their careers will be obliterated within a mere 15 days of the regulations taking effect. Such fear-mongering often brands these progressive rules as “black laws,” in stark contrast to viewing existing structures upholding inequality as acceptable or ‘white laws’. Imagine framing protection measures as criminal statutes—this is the level of distortion we witness.

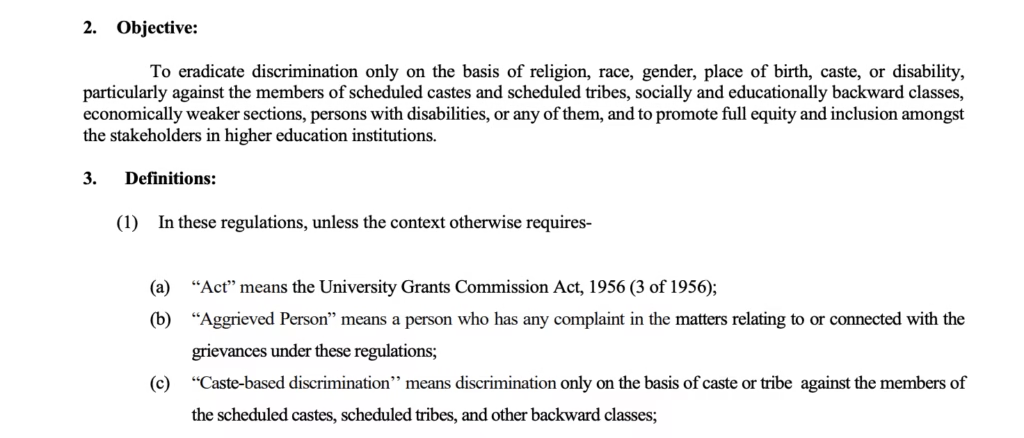

Key Features of the UGC Equity Guidelines 2026

The 2026 regulations represent a significant hardening of stance compared to previous iterations. The perceived strictness is precisely what has caused alarm among the dominant sections. The core objective remains the eradication of caste discrimination, aligning with constitutional mandates for justice and equality. However, the mechanisms introduced are substantially more robust, promising real accountability where previous systems often failed.

Inclusion of OBCs in Protection Frameworks

One of the most crucial differences in the 2026 guidelines is the expansion of the protected class. While previous mechanisms largely focused on SC and ST communities, the new regulations explicitly incorporate OBC students into the framework for reporting and seeking redressal against caste-based discrimination. Considering that OBCs form a significant portion of the population aspiring for higher education—and given that SC, ST, and OBCs together constitute about 60% of students accessing higher education, compared to the GC’s 40% share—this inclusion significantly widens the net of protection.

This means that 60% of the student body now has explicit recourse against discrimination from the other 40%, which is perceived by the dominant group as shifting the balance of power and potential accountability.

Strict Accountability Measures for Institutional Heads

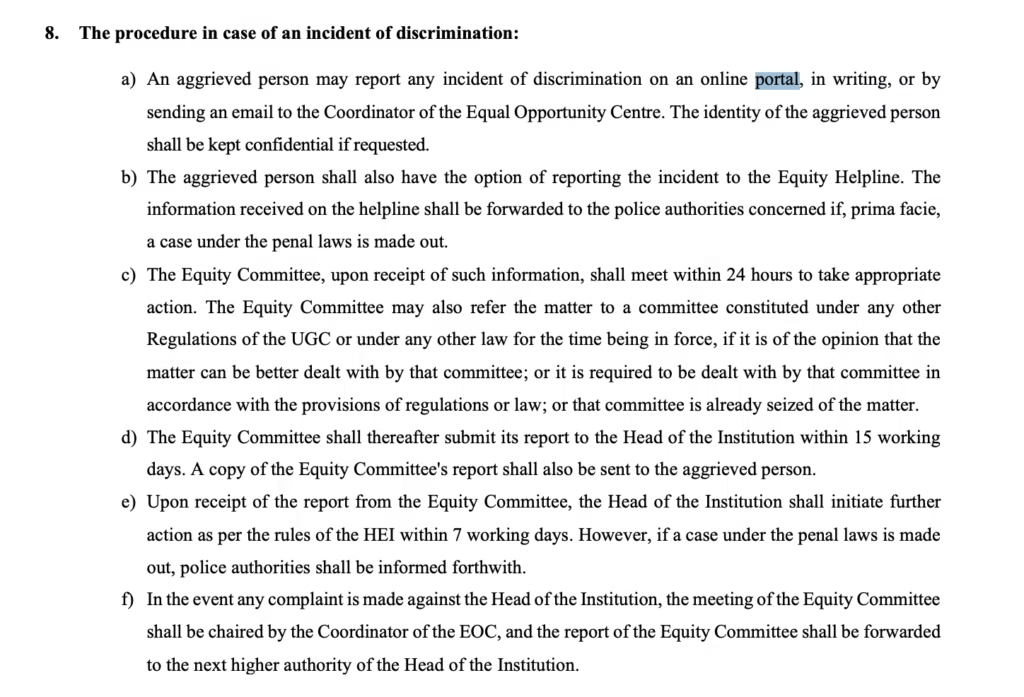

A cornerstone of the new framework is the direct imposition of responsibility upon institutional leadership. Under these guidelines, the Vice-Chancellor, Principal, or head of the institute is held directly responsible if a reported incident of discrimination occurs on campus. This is a substantial shift, as these leadership roles are predominantly held by individuals from the dominant castes. The immediate accountability places significant pressure on them to act decisively. Furthermore, a fast-track system has been mandated: initial action must be taken within seven days of receiving a complaint, with the entire resolution process expected to conclude within 45 to 60 days. This stands in stark contrast to the historical practice where complaints often languished for years, allowing harassment to continue unchecked.

Elimination of Penalties for Complainants

A major historical deterrent to filing complaints was the fear of retribution, often formalized through rules suggesting penalties for ‘false’ or unproven complaints. Students, being relatively young and often lacking extensive resources or understanding of legal nuances, were easily intimidated. The 2026 guidelines abolish the provision for penalizing complainants if the complaint is not ultimately proven. This is designed to encourage students to speak out freely about caste-based offenses without fear of counter-action or penalty, thereby prioritizing the safety of the reporting individual over concerns about frivolous litigation. The underlying premise is that the gravity of caste discrimination warrants a system where the primary focus is on ensuring victims can report without self-censorship.

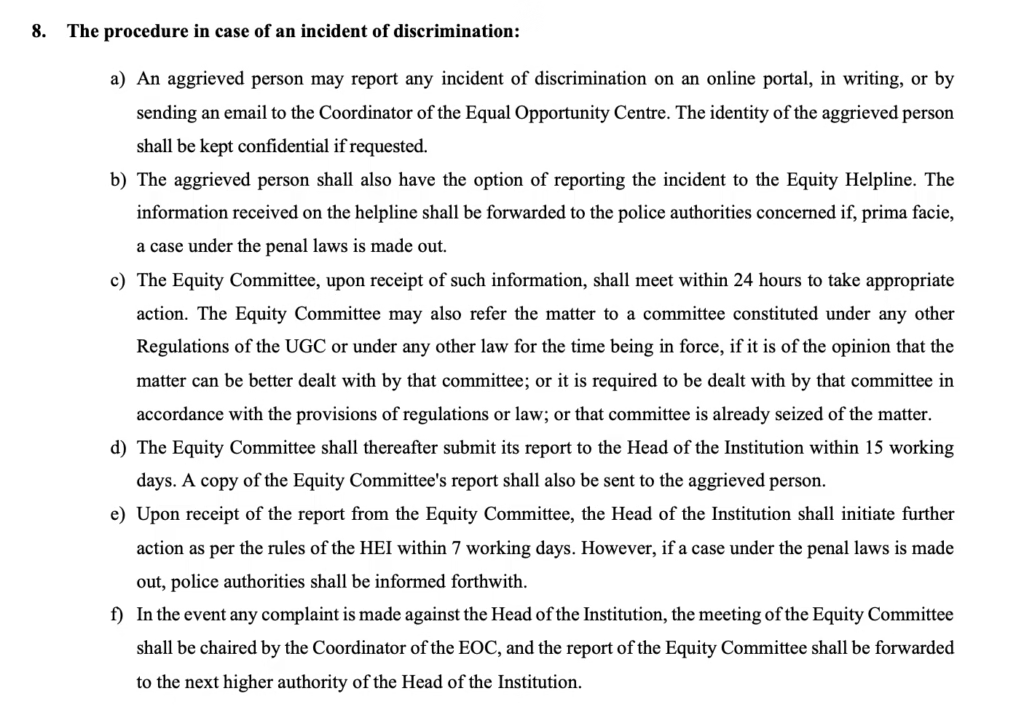

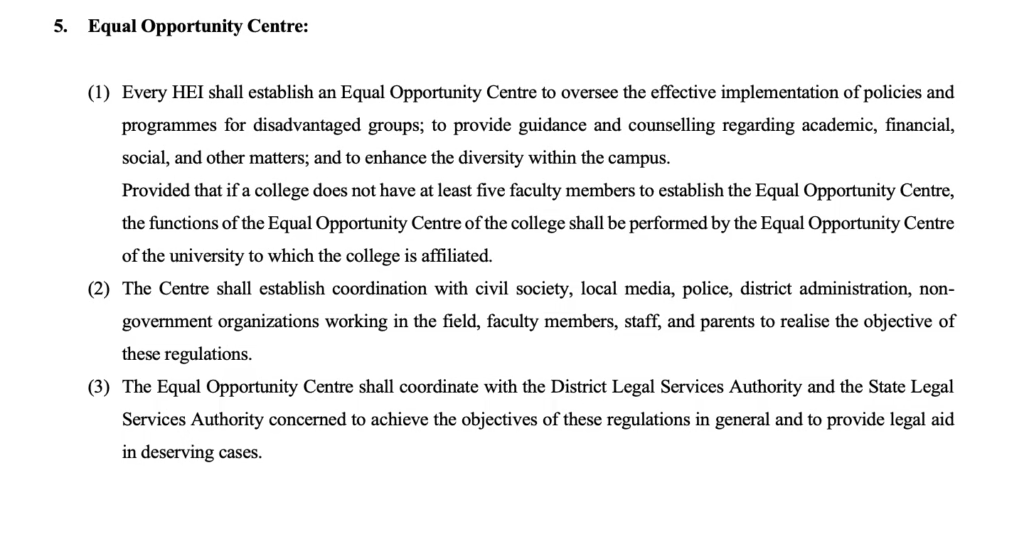

Institutional Mechanisms for Equity Enforcement

To ensure these guidelines are not merely administrative platitudes but functional tools for change, the UGC mandates the creation of a multi-tiered enforcement structure within every HEI.

The Role of Anti-Discrimination Bodies

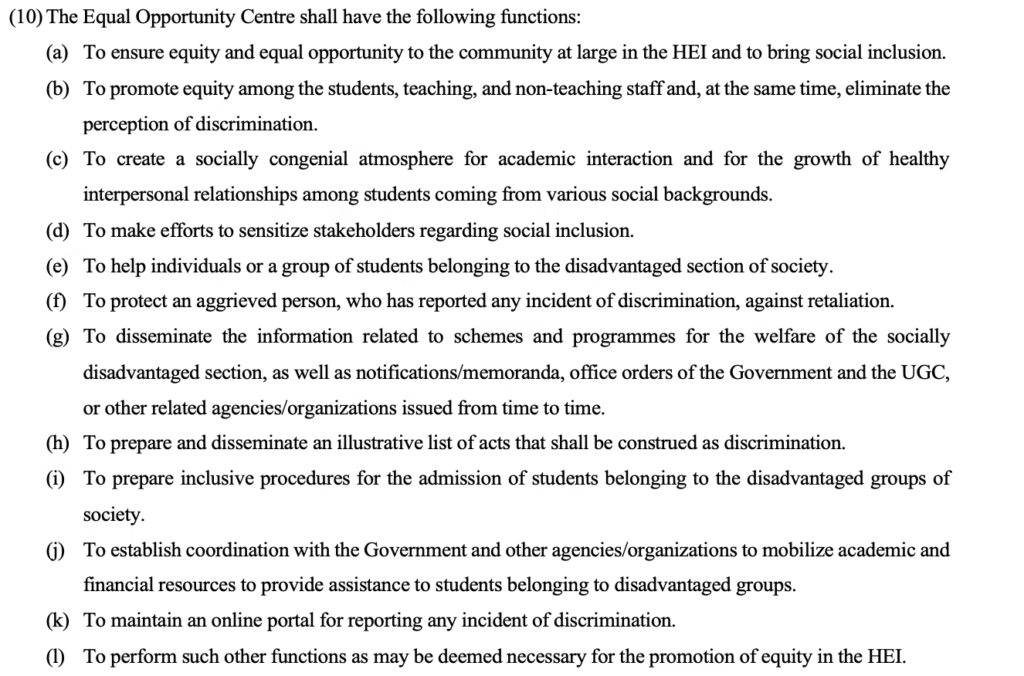

The regulations necessitate the establishment of several key bodies. First, an Anti-Discrimination Officer (ADO) must be appointed as a nodal officer to whom complaints can be addressed directly, either in writing or via email. Second, an Equal Opportunity Centre (EOC) will be established on campus, featuring a dedicated desk for handling discrimination-related issues. Finally, an Equity Committee (EC), comprising representatives from SC, ST, OBC, female students, and other relevant stakeholders, will oversee specific complaints. Furthermore, an Equity Squad (ES), analogous to the existing Anti-Ragging Squads, will conduct surprise inspections to proactively check for ongoing discrimination and report directly to the VC, ensuring preventative measures are in place.

Digital Grievance Redressal Systems

Recognizing the need for accessibility and confidentiality, the guidelines mandate the integration of technology into the grievance mechanism. Every institution is required to establish a dedicated Equality Complaint Portal on its website. Crucially, this portal must allow complainants to lodge grievances anonymously, safeguarding their identity. In addition to the online portal, a 24-hour helpline will be established. This emphasis on digital and confidential reporting mechanisms directly tackles historical barriers where public complaints often exposed victims to immediate backlash, harassment, or social boycotts, which tragically led to incidents such as the suicides of individuals like Rohit Vemula.

Protection Against Retaliation and Third-Party Reporting

The framework incorporates strong protections against victim-blaming and retaliation. The guidelines explicitly define acts of revenge, such as intentionally lowering marks in exams, withholding scholarships, or eviction from hostels (recalling the treatment of Rohit Vemula) as prosecutable offenses under these regulations. A particularly progressive addition is the provision allowing third parties—friends, classmates, or parents—to file a complaint on behalf of the victim. This recognizes that victims, especially in vulnerable states of mental distress or isolation, may not always be able to initiate action themselves. If retaliation occurs against the complainant, severe financial penalties can be levied against the responsible individuals and the institution itself.

The Historical Context: Failures of Past Guidelines

The current stringent framework did not arise spontaneously. It is a direct response to repeated systemic failures, evidenced by high-profile tragedies that drew Supreme Court intervention.

The Aftermath of Tragic Suicides

The suicides of students like Rohit Vemula and the case of Payal Tadvi brought the pervasive nature of casteism in HEIs to national scrutiny. Following the uproar post-Vemula’s death, the Supreme Court critically reviewed the existing regulations for handling caste-based issues in higher education. The Court found the prevailing guidelines, dating back to 2012, to be inadequate for effectively tackling the complex and often subtle forms of discrimination prevalent in modern campuses and directed the government and UGC to revise and strengthen them.

The Flawed 2025 Guidelines

Under pressure from the Supreme Court, the UGC released revised guidelines in March 2025. However, these 2025 regulations were met with widespread criticism from activists and legal experts. They were often deemed worse than the 2012 rules, as they allegedly failed to clearly define caste-related offenses and, worryingly, included provisions that could penalize complainants.

This flawed attempt at reform only intensified scrutiny, leading to further reprimands from the Supreme Court. The current 2026 regulations are thus a direct consequence of the government being compelled by judicial and social pressure to rectify the shortcomings of the previous year’s attempt.

The Political Economy of Resistance and Compliance

The fervor surrounding the opposition to the 2026 guidelines must be understood through the lens of India’s complex political dynamics, which thrive on division.

The Role of Legal Activism and Judicial Scrutiny

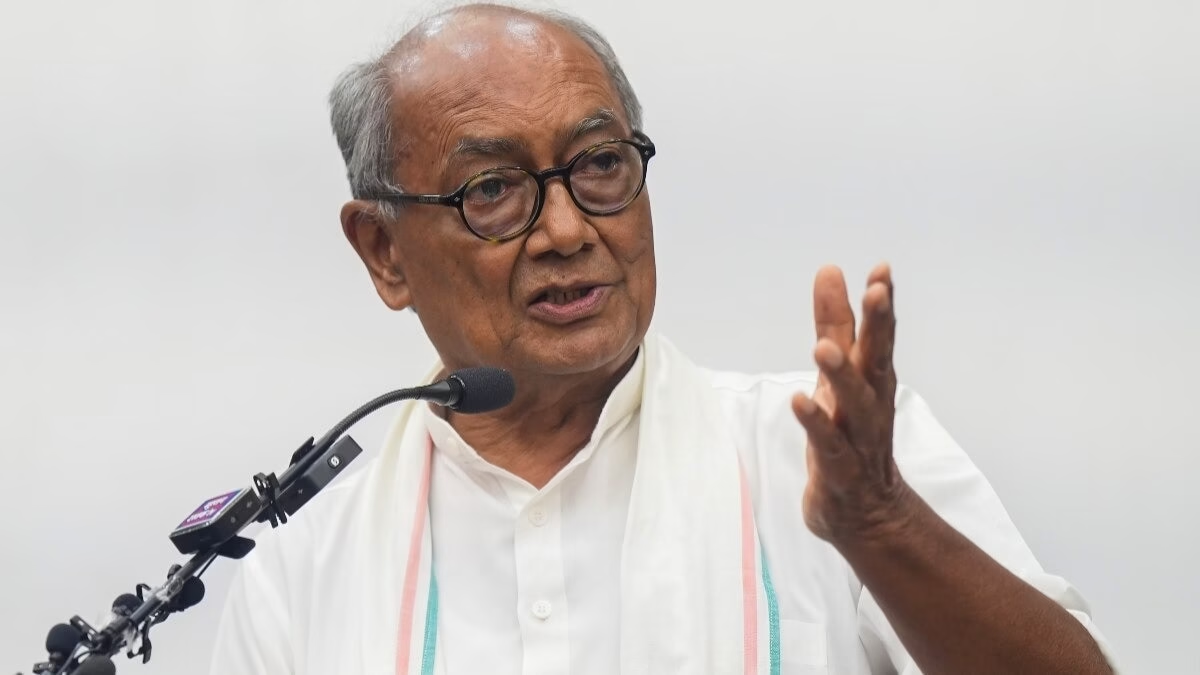

It is vital to note that the strength of the 2026 guidelines is not merely a benevolent act by the current administration. Legal advocates fought relentlessly in the Supreme Court. Furthermore, the significant role played by certain political figures, notably senior Congress leader Digvijaya Singh, has been highlighted. As the chairman of a relevant Parliamentary Committee, Singh’s committee reportedly submitted strong recommendations advocating for harsher penalties and the inclusion of OBCs under the protective umbrella.

His committee’s pressure ensured that provisions for strict penalties (like affiliation cancellation) and the mandatory inclusion of private colleges were incorporated into the final draft. This background underscores that these strong measures resulted from sustained pressure from the judiciary, social activists, and parliamentary oversight, rather than purely administrative initiative.

The Divide and Rule Strategy

The political benefit derived from this conflict is deeply strategic for the ruling party. By allowing or engineering situations where dominant castes feel under siege (by perceived ‘harsh’ laws) and simultaneously allowing conservative factions within the dominant castes to mobilize against these laws, the party solidifies its core vote bank. The narrative promoted is one where the rights of SC/ST/OBC are pitted directly against the perceived ‘merit’ and future of the GC.

This polarization ensures that the dominant community, fearing a loss of status and believing their historical privileges are under threat from marginalized communities and religious minorities, remains tethered to the ruling political alignment. Meanwhile, certain leaders exploit the situation by selectively messaging marginalized groups about the government’s protection, thereby achieving advantage from both sides of the conflict.

Addressing the Criticisms from the Dominant Narrative

Those opposing the guidelines often rely on several recurring, though heavily disputed, arguments against the spirit of equality.

The False Narrative of ‘False Complaints’ and Merit Erosion

A primary objection centers on the fear of false complaints. Opponents argue that any law can be misused, citing hypothetical instances where caste-based claims might be fabricated out of personal enmity. However, this objection is often countered by pointing out that all major laws, including those concerning terrorism (like UAPA) or sexual assault, are susceptible to misuse, yet the necessity of these laws to tackle real, widespread harm remains paramount.

A secondary argument suggests that the enforcement mechanism, particularly the Equity Committee, will unduly burden institutional heads and erode academic excellence (merit) by prioritizing ‘balance’ over scholarly rigor. This contention is challenged by the assertion that current ‘merit’ is often a product of systemic inequality and caste bias, and genuine equity leads to fairer competition, thus fostering authentic merit.

Autonomy and Overly Broad Definitions of Discrimination

Concerns about the erosion of institutional autonomy have also been raised, particularly by private universities, who fear intrusive oversight from bodies like the Equity Squads. Furthermore, critics claim the definition of discrimination is too broad, potentially encompassing minor classroom discussions. This claim is refuted by the fact that the guidelines target actual misconduct and harassment. The call for broad definitions is necessary because casteism is insidious and often manifests in subtle, conversational forms—jokes, casual slurs, and microaggressions—that perpetrators attempt to dismiss as mere ‘joking’ or ‘banter.’ The guidelines aim to eliminate these behaviors at their root.

The Impossibility of ‘Reverse Casteism’

A persistent, though structurally flawed, argument is the fear that SC/ST/OBC individuals will now commit ‘casteism’ against the dominant groups. This argument ignores the structural definition of casteism, which is institutionalized discrimination backed by social, economic, and historical power structures. In the context of Indian HEIs, where power remains concentrated in the hands of the dominant castes in administrative and faculty roles, the notion that lower-caste individuals can wield systemic discriminatory power against their superiors is generally dismissed as logically unsound. The UGC Equity Guidelines 2026 are structured to address historically rooted power imbalances, not isolated incidents of interpersonal conflict lacking structural support.

The Unfinished Struggle: Why the 2026 Regulations Still Fall Short

While the new guidelines are a step forward, they contain significant loopholes that threaten the very students they claim to protect. We must remain vigilant. Here are 10 reasons why the UGC Equity Regulations 2026 require an immediate relook:

- Exclusion of IITs and IIMs: These regulations do not apply to IITs/IIMs, which are governed by separate acts. These are the very institutions where the highest number of caste-based suicides occur.

- Dilution of “Discrimination”: The 2012 definition included specific scenarios like “harassment” and “victimization.” The 2026 version is vague, giving too much discretion to university heads.

- Removal of Admission Protections: Specific clauses protecting SC/ST students from discrimination during the admission process (withholding degrees, extra fees) have been removed.

- Absence of Classroom Conduct Rules: Provisions against verbal caste slurs, labeling students “reserved,” or differential treatment in labs have been deleted.

- Lack of Evaluation Oversight: The deterrent against casteist professors manipulating marks or delaying results has been stripped away.

- Fellowship Vulnerability: Protections for Ph.D. fellowships have been removed, leaving research scholars vulnerable.

- Diluted Common Space Protections: Specific mentions of hostel segregation and exclusion from cultural/sports events are missing.

- The “Clubbing” Problem: By merging EWS and Physical Disability into the same cell as SC/ST/OBC, the unique social disability of caste is equated with economic or physical factors. This risks the cell being used by dominant groups to file counter-cases.

- Absence of Liaison Officers: DOPT mandates Liaison Officers for SC/ST/OBC representation, yet they are not integrated into this new Equity Cell.

- The Need for Separate Cells: A “common” cell only works with 50-75% marginalized representation. Otherwise, it leads to a dilution of focus on the groups facing the most severe systemic violence.

Conclusion: The Significance of Enforceable Equity

The UGC Equity Guidelines 2026, despite the intense, predictable backlash, represent a potentially transformative step toward dismantling caste-based oppression in Indian academia. The introduction of swift adjudication, direct accountability for leadership, mandatory anonymous reporting, and the inclusion of OBCs creates a theoretically powerful framework. If these regulations are implemented effectively on the ground, the current climate where casteism flourishes beneath a veneer of modernity will become untenable for perpetrators. The current resistance signals a recognition by the privileged that their long-held, unearned advantages are finally facing a structural threat.

What you can do?

The successful implementation of these guidelines hinges on continuous vigilance and active participation from the communities they are designed to protect. Citizens must support the spirit of these regulations against vested interests attempting to derail them. Educate yourself on the details of the 2026 regulations to counter misinformation spread on social media.

If you witness or experience caste-based discrimination in any HEI, utilize the newly established mechanisms—the ADO, the EOC, or the digital portal—to report it promptly. Do not be deterred by the scaremongering tactics; the law now theoretically protects the complainant. Furthermore, engage with social justice organizations and legal advocates who are monitoring the actual ground-level enforcement of these crucial reforms. Your sustained attention is necessary to ensure these guidelines do not fade into bureaucratic oblivion.

Disclaimer: This article analyzes the content provided regarding the UGC Equity Guidelines 2026. Common terms used in this context are defined as follows: General Category (GC) refers to the unreserved category, often associated with dominant castes; SC/ST/OBC refer to Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and Other Backward Classes, respectively, marginalized social groups; Equity refers to fairness and justice in opportunity, often requiring differential treatment to correct historical disadvantages; Casteism refers to discrimination based on caste identity; and Privileges refer to unearned advantages enjoyed by dominant groups historically.

Read more about IIT IIM Reservation: Caste Bias & Solutions (Data Driven)

Find out more about Truth About IIT IIM Dropout Rates: Beyond Headlines

Do you disagree with this article? If you have strong evidence to back up your claims, we invite you to join our live debates every Sunday, Tuesday, and Thursday on YouTube. Let’s engage in a respectful, evidence-based discussion to uncover the truth. Watch the latest debate on this topic below and share your perspective!