The Pervasive Influence of Brahmanical Rituals in India

The concept of sanskar, or sacraments, is deeply ingrained in Indian culture. The Brahmanical system outlines 16 commonly known rituals, but historical texts reveal a more extensive and complex system, with some traditions mentioning up to 40 or even 48 distinct sanskars. While the widely recognized 16 sanskars, as detailed in the Vyasa Smriti, remain prevalent today, many others have faded into obscurity. This exploration delves into the origins and implications of these rituals, particularly focusing on the Garbhadhan Sanskar, and critically examines the role of the priestly class in perpetuating practices often rooted in superstition rather than rational thought. Some discussions may touch upon sensitive topics; viewers under 18 are advised to proceed with caution.

Table of Contents:

- Understanding the Brahmanical System's Life Cycle Framework

- Post-Natal Rituals: From Birth to Naming

- Mid-Life Sanskars: Physical and Social Development

- Transition to Adulthood: Upanayana and Vidyarambh Sanskars

- Culmination of Life: Marriage and Final Rites

- The Pervasive Influence and Exploitation by the Priestly Class

- The Myth of 'Vedic Science' and Its Flaws

- Conclusion: Moving Beyond Superstition and Exploitation

Understanding the Brahmanical System’s Life Cycle Framework

The Brahmanical system, as documented in various scriptures, meticulously governs every stage of human life through a series of rituals. These sanskars, often numbering more than the commonly known 16, served not only as religious observances but also as mechanisms for social control and the reinforcement of the caste hierarchy. The Gautam Smriti, for instance, refers to 40 sanskars, while other texts mention 48. Maharishi Angira’s teachings suggest 25 sanskars, and the Vyasa Smriti provides the framework for the 16 sanskars most commonly practiced today.

These sanskars are presented as essential for achieving desired outcomes, such as the birth of a virtuous child or spiritual merit. The priestly class, or Brahmins, played a central role in administering these rituals, positioning themselves as indispensable intermediaries between the divine and the laity. This monopoly over religious knowledge and practice allowed them to exert significant influence over society. The subsequent sections will dissect specific sanskars, starting with Garbhadhan Sanskar, to understand their purported objectives and the methods employed in their execution.

The Premise of Garbhadhan Sanskar: Conception and Procreation

The Garbhadhan Sanskar, the very first ritual in the Brahmanical life cycle, marks the initiation of procreation. This ritual is performed with the explicit aim of ensuring the birth of a desired child, often with a preference for a male offspring, reflecting the patriarchal underpinnings of the system. The texts suggest that through this sanskar, couples can conceive a child with specific qualities—intelligence, physical prowess, or adherence to prescribed social norms. The process involves elaborate rituals and chanting of mantras, with the priest guiding the couple through the act of conception. The ultimate goal, as presented in these scriptures, is to produce an ‘ideal’ child who will uphold the family’s lineage and social standing.

This sanskar underscores the Brahmanical belief that even the most intimate human act, procreation, is subject to divine intervention and priestly guidance. The emphasis on producing a son further highlights the societal value placed on male heirs, who were traditionally responsible for continuing the family line and performing ancestral rites. The concept of ‘desired progeny’ raises ethical questions about reproductive choices and the potential for coercion or manipulation within such ritualistic frameworks.

The priest’s role in this personal act signifies the deep penetration of religious and social control into individual lives within the Brahmanical tradition. Attempting to influence conception solely through rituals without understanding the biological underpinnings is like trying to fix a complex machine by simply chanting at it, ignoring the mechanics and engineering.

The Ritualistic Process and Underlying Beliefs

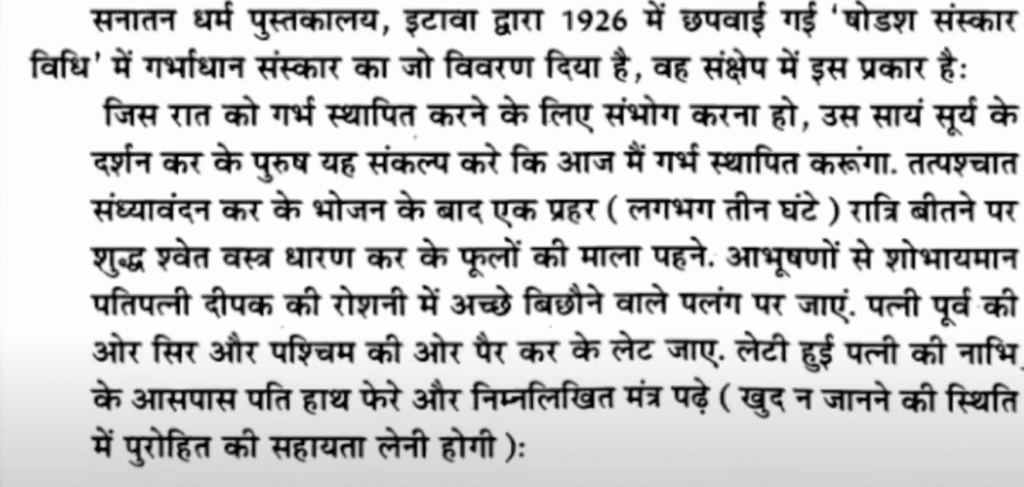

The Garbhadhan Sanskar, as described in ancient texts, outlines a specific ritualistic process. It begins with the husband making a solemn vow to procreate, often in the evening after sunset. This vow is taken after performing evening prayers (Sandhya Vandan) and consuming a meal. Following this, at approximately three hours past sunset, the couple adorns themselves in clean white garments and floral garlands. They then proceed to a well-adorned bed, illuminated by lamps.

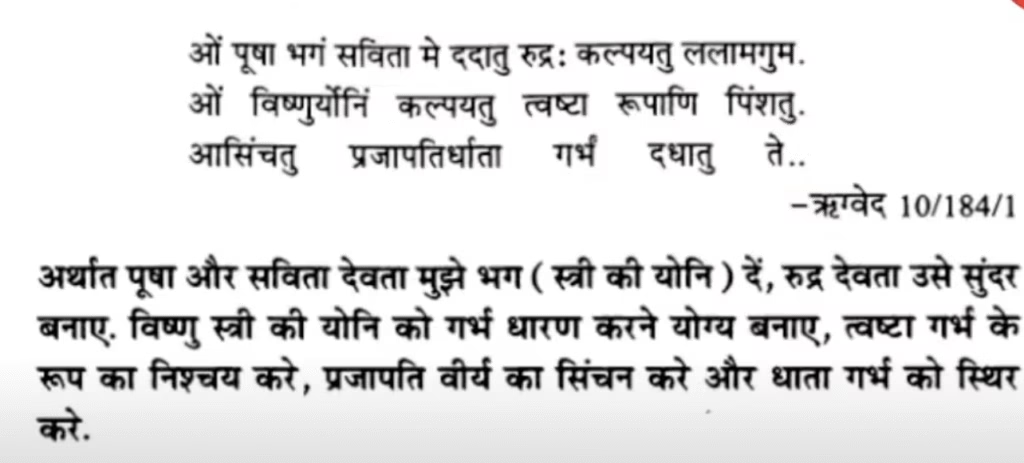

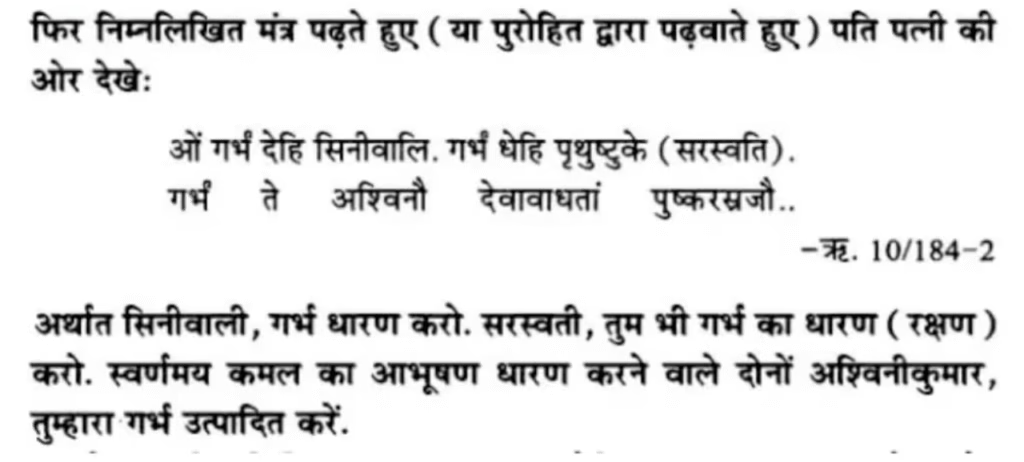

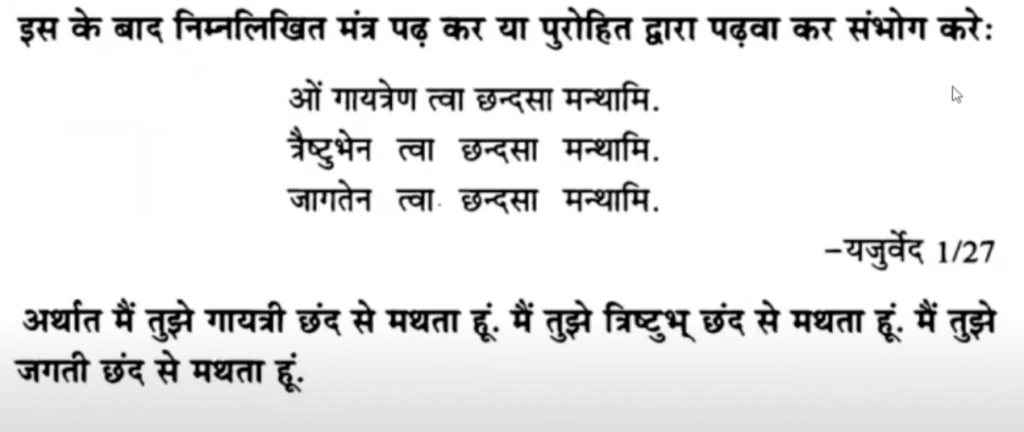

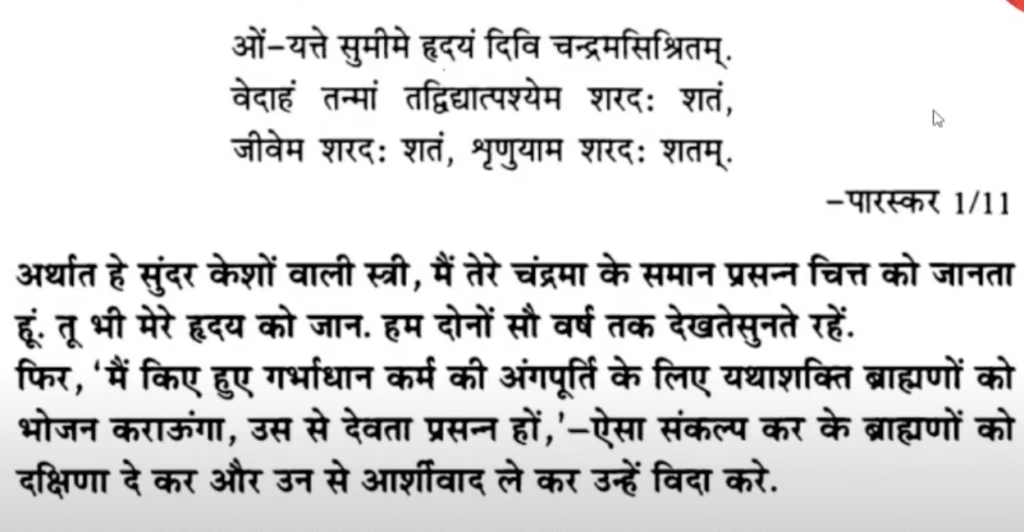

The wife lies down with her head facing east and her feet towards the west. The husband gently touches his wife’s navel area while reciting specific mantras, often derived from the Rigveda (Mandala 10, Sukta 84, Verse 2). These mantras invoke deities like Pushan and Savita, requesting the boon of progeny.

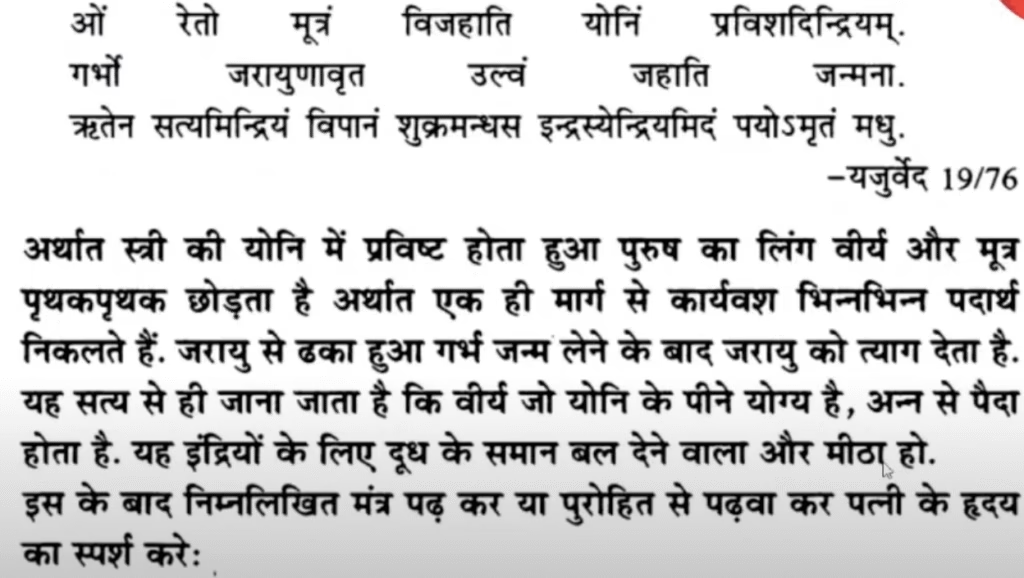

The literal translation of these verses often involves explicit references to female anatomy and procreation, underscoring the ritual’s overtly sexual nature; for instance, seeking the ‘yoni’ (vagina) and praying for its fertility. Following this, to facilitate intercourse, further mantras are recited, often from the Yajurveda. These verses describe physiological aspects of reproduction in a manner that is both explicit and, by modern scientific understanding, highly unscientific.

The entire process is steeped in a belief system that posits divine involvement in conception and emphasizes the need for ritualistic purification and invocation even during sexual intercourse. The priest’s role, if the couple cannot recite the mantras themselves, is to chant them, further highlighting dependence on the priestly class for fundamental life processes. This detailed ritualistic approach to conception reveals a deep-seated belief that procreation is not merely a biological event but a sacred act requiring divine sanction and priestly mediation.

Criticism of Garbhadhan Sanskar

Modern interpretations and critiques of the Garbhadhan Sanskar highlight its unscientific and potentially harmful aspects. Scholars and rationalists argue that the elaborate rituals, mantra chanting, and invocation of deities during conception are rooted in superstition rather than biological fact. The emphasis on specific times and procedures for intercourse, as dictated by the supposed “science” of the time, is seen as a means of control and a reflection of a primitive understanding of reproductive biology. The use of explicit and potentially offensive language in the mantras, even during procreation, is contentious, raising questions about the ethical and psychological impact on the couple.

Furthermore, the prescription for a priest’s presence or chanting, if the couple is unable, highlights dependence on the priestly class and their fees, which can burden ordinary people. The notion that specific days or times, dictated by the lunar calendar, influence the sex of the child is widely dismissed by modern science. The texts suggest intercourse on certain nights results in a male child, while others result in a female child—a scientifically unfounded concept. Reliance on such unverified beliefs can lead to anxiety and distress for couples with fertility issues, pushing them towards expensive and ineffective rituals.

Modern Interpretations of Garbhadhan Sanskar

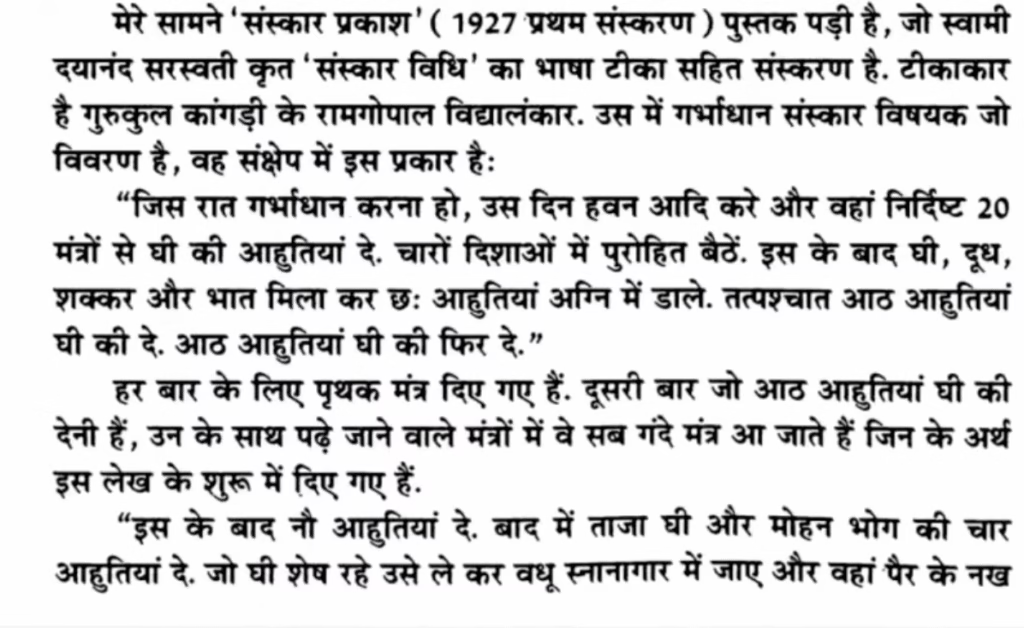

The elaborate rituals involving ghee, milk, and other offerings during the sanskar also represent a significant waste of resources, especially in a country grappling with poverty and hunger. Modernized versions of the Garbhadhan Sanskar, as proposed by figures like Swami Dayanand Saraswati, while attempting to sanitize the rituals, often retain core unscientific beliefs and add layers of complexity and expense, such as elaborate हवन (fire rituals) with multiple priests.

Critics argue this transformation does not eliminate superstition but repackages it, making it more palatable while still perpetuating dependence on the priestly class and wasteful practices. The overall critique is that these rituals, rather than contributing to a healthy, rational approach to procreation, foster a culture of blind faith, superstition, and economic exploitation.

The Spectrum of Sanskars: From Conception to Death

While Garbhadhan sets the stage for life, the Brahmanical system’s influence extends far beyond conception, encompassing a comprehensive array of rituals throughout an individual’s life. These range from prenatal influences to post-natal purification, developmental milestones, transitions to adulthood, marriage, and finally, funeral rites. These sanskars highlight a profound desire to control and influence outcomes that are largely governed by biological and genetic factors, reflecting a worldview where divine intervention and ritualistic practice can supersede natural processes. Could it be that the elaborate system of sanskars was not just about spiritual purity, but also a sophisticated method of social engineering?

Prenatal Rituals: Punsavan and Simantonnayan Sanskars

Even before a child’s first breath, the Brahmanical tradition prescribes sanskars to influence fetal development. The Punsavan Sanskar, performed during the second or third month of pregnancy, aims to ensure the birth of a male child and the healthy development of the fetus.

The Simantonnayan Sanskar, performed between the sixth and eighth month of gestation, is believed to purify the fetus and prepare it for learning. The narrative surrounding these rituals often invokes mythological examples, such as Abhimanyu in the Mahabharata, who is said to have learned the art of entering the Chakravyuh while still in his mother’s womb.

This connection to epic tales legitimizes the sanskars and imbues them with ancient wisdom and divine efficacy. The underlying belief is that through these rituals, parents can actively shape their unborn child’s destiny and capabilities, ensuring it is born with desirable qualities and intellectually predisposed to learning. Priests, through mantras and rituals, facilitate this prenatal development, positioning themselves as essential guides. These sanskars underscore a desire to control development before birth, imbuing the child with qualities deemed essential for success and righteousness.

Punsavan Sanskar: Ensuring a Male Heir

The Punsavan Sanskar specifically targets the child’s sex, with a strong emphasis on the birth of a son. Typically performed in the second or third month of pregnancy, this ritual aims to ensure the developing fetus is male. The accompanying mantras and rituals are believed to directly impact reproductive outcomes. Scriptures suggest that if the couple desires a son, the Punsavan Sanskar is essential. This ritual highlights the deeply patriarchal nature of the Brahmanical system, where a son was paramount for lineage continuation, inheritance, and ancestral rites. The fear of not having a male heir often led to intense societal pressure on women; rituals like Punsavan were presented as a means to alleviate this anxiety.

The efficacy of this sanskar is scientifically unsubstantiated. Modern genetics clearly explains that the sex of a child is determined by the father’s chromosomes. Despite the lack of scientific basis, the belief in such rituals persisted for centuries, highlighting the influence of religious and social conditioning. The Punsavan Sanskar stands as a stark example of how deeply ingrained gender biases were embedded within religious practices, dictating even the most intimate aspects of family life.

Simantonnayan Sanskar: Fetal Learning and Purity

The Simantonnayan Sanskar, performed during the sixth to eighth month of pregnancy, focuses on the purity and intellectual development of the fetus. This ritual is believed to cleanse the womb and prepare the unborn child for learning. The concept of prenatal learning, while intriguing, is often presented in a manner that stretches scientific plausibility. The story of Abhimanyu from the Mahabharata, who learned the secrets of the Chakravyuh in his mother’s womb, is frequently cited as an example of such prenatal influences. This narrative suggests that through specific rituals and perhaps even by reciting knowledge aloud near the pregnant mother, the fetus can absorb information and develop cognitive abilities.

Priests, through mantras and rites, are believed to facilitate this process. The Simantonnayan Sanskar reflects a desire to exert maximum control over the child’s development, even before birth, and to imbue it with qualities deemed essential for success and righteousness. This belief in prenatal influence also speaks to a broader cultural understanding of the interconnectedness between the spiritual and physical realms, where rituals are seen as a means to bridge the gap and influence outcomes. However, from a scientific perspective, while a fetus can respond to external stimuli like sound, the complex learning attributed in these myths remains largely unsubstantiated.

Post-Natal Rituals: From Birth to Naming

Rituals continue after birth, with sanskars designed to purify the newborn, ensure well-being, and formally integrate the child into the social and religious fabric. The Jatakarma Sanskar, performed immediately after birth, aims to remove impurities or ailments acquired in the womb. Following this, the Namkaran Sanskar, or naming ceremony, typically held between the eleventh and twelfth day, assigns the child its name based on astrological considerations. These early post-natal rituals highlight the Brahmanical emphasis on purity and the belief that external intervention is necessary for a healthy and auspicious start to life. The priests’ role solidifies their position as guardians of life’s transitions.

Jatakarma Sanskar: Purification at Birth

The Jatakarma Sanskar is one of the earliest rituals for a newborn, performed immediately following its birth. This ceremony intends to cleanse the infant of any impurities or diseases contracted prenatally or during birth. It is believed that performing this sanskar removes negative influences and ensures a healthy beginning. A key element involves feeding the newborn a mixture of honey and ghee (clarified butter) using a gold or silver spoon, or a ring finger.

This practice contradicts modern medical advice, which strongly recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months. Medical professionals emphasize that introducing any other substance, including honey, before one year can be harmful due to the risk of infant botulism and other health complications. The belief that honey and ghee possess medicinal properties counteracting birth-related ailments is a cornerstone of traditional Ayurvedic practices, but their administration to newborns without medical supervision is risky. The Jatakarma Sanskar exemplifies a tradition where ancient beliefs about purification and healing, often lacking scientific validation, continue to influence critical infant care practices.

Namkaran Sanskar: The Significance of a Name

The Namkaran Sanskar, or naming ceremony, is a significant ritual performed on the eleventh to the twelfth day after birth, though some texts suggest the tenth to the twelfth day. This ceremony formally assigns a name to the child, a name believed to carry astrological significance and influence destiny. A Brahmin priest, using astrological charts and calculations, determines an auspicious name, often considering celestial positions at birth. The child is also presented with honey to taste and shown the sun, symbolizing a blessing for a bright future.

The practice of assigning names based on astrology reflects a worldview where celestial bodies are believed to impact human lives. While naming a child is universal, the Brahmanical approach imbues it with religious and astrological importance, positioning the priest as the arbiter of destiny. This ceremony marks the child’s official entry into the family and community, providing an identity rooted in tradition and divine decree. The emphasis on auspiciousness and the priest’s role highlight the pervasive influence of Brahmanical rituals in shaping personal aspects of life from inception.

Mid-Life Sanskars: Physical and Social Development

As individuals progress through life, sanskars mark significant developmental stages. These include rituals like Nishkraman Sanskar, Annaprashan Sanskar, Mundan Sanskar, and Karna Vedhan Sanskar, each with prescribed actions and purported benefits. These sanskars aim to foster physical and mental development, ensure protection from ill effects, and prepare the individual for social integration. They highlight the Brahmanical belief in the continuous need for ritualistic intervention throughout life for well-being and spiritual progress.

Nishkraman Sanskar: Introduction to the World

The Nishkraman Sanskar, typically performed between the fourth and sixth month after birth, signifies the infant’s first emergence from home into the outside world. This ritual is believed to benefit the child’s overall well-being and longevity. During this ceremony, the infant is often taken out to be shown to celestial bodies like the sun and moon, and deities are worshipped. This act symbolizes the child’s introduction to cosmic forces, seeking blessings for protection and prosperity. The ceremony involves prayers and offerings to various deities, invoking their grace.

The concept of introducing the child to the sun and moon reflects an ancient understanding of the natural world and its perceived influence on human life. It signifies a transition from the private, domestic sphere to the larger, public realm, marked by a spiritual acknowledgment of universal governing forces. The belief is that exposing the child to these celestial bodies and divine energies blesses it with strength, vitality, and a long life. This ritual underscores the Brahmanical worldview, where even the simple act of stepping outside is imbued with religious significance and requires divine sanction.

Annaprashan Sanskar: First Solid Food

The Annaprashan Sanskar, meaning ‘first feeding of rice,’ is a milestone celebrated around six to seven months of age, when the infant develops teeth and a stronger digestive system. This ritual marks the introduction of solid food, typically kheer (rice pudding), to the infant’s diet, symbolizing the transition from a milk-based diet to a more diverse intake. The ceremony involves parents offering the first spoonful of food to the child, often using a gold or silver spoon, while chanting specific mantras. The purpose is to ensure the child’s first solid food is pure and auspicious, free from negative influences.

Priests often perform a purification ritual before feeding, involving prayers and offerings to deities. This sanskar signifies a crucial step in the child’s physical development, marking growing independence and capacity for nourishment. It is a moment of celebration, acknowledging the child’s progress and seeking divine blessings for continued growth and health. The ritual reinforces the belief that even introducing solid food is a sacred act requiring religious sanctification for the child’s well-being and auspicious future.

Mundan Sanskar: Head Shaving Ceremony

The Mundan Sanskar, also known as tonsure or Chudakarma Sanskar, involves the ritualistic shaving of the infant’s head, typically between the first and third year of life, often around the first birthday or during the third year. The primary belief is that shaving the head removes impurities accumulated in the womb and promotes healthy hair growth, strength, and intellect. After shaving, the head is often smeared with curd and butter, followed by a ritualistic bath.

The rationale is rooted in ancient beliefs about purification and the auspiciousness of new beginnings. Removing birth hair is thought to shed negative energies or influences. The Mundan Sanskar is also a symbolic shedding of the past, preparing the child for a new life phase. While head shaving is common across cultures, in the Brahmanical context, it is imbued with spiritual significance, aiming to enhance physical and mental vitality. This ritual highlights the continuous engagement of the priestly class in guiding child development, even in matters of physical appearance and hygiene.

Karna Vedhan Sanskar: Ear Piercing Ritual

The Karna Vedhan Sanskar, or ear piercing ceremony, is an important ritual performed during childhood, typically between six months and five years of age. This practice, common in many cultures, holds particular significance in the Brahmanical tradition. It is believed that piercing the ears offers benefits including improved health, spiritual awareness, and protection from negative energies. Tradition holds that piercing allows sunlight to enter the ear canal, purifying the body and mind. It is also thought to enhance hearing and improve the flow of vital energy.

For girls, ear piercing is often accompanied by wearing earrings, considered decorative and auspicious. For boys, it marks a transition toward manhood. The ritual is often performed by a priest or skilled artisan, with specific mantras chanted for a smooth and auspicious procedure. The Karna Vedhan Sanskar reflects the belief that the body is a vessel needing ritual preparation and protection, and that certain physical modifications, guided by religious principles, can lead to enhanced well-being and spiritual progress. This practice, like many others, underscores the pervasive influence of Brahmanical rituals in shaping life aspects, from birth to physical adornment.

Transition to Adulthood: Upanayana and Vidyarambh Sanskars

As individuals approach adolescence, the Upanayana Sanskar marks a significant transition, signifying a ‘second birth’ and the commencement of formal education, particularly in Vedic studies. This is followed by the Vidyarambh Sanskar, the formal initiation into learning. These sanskars are pivotal in shaping an individual’s social and intellectual identity within the Brahmanical framework, often reinforcing caste distinctions and restricting access to knowledge.

Upanayana Sanskar: The Sacred Thread and Second Birth

The Upanayana Sanskar, often called the sacred thread ceremony, is a pivotal ritual marking the transition to adolescence and the beginning of formal education for Brahmin, Kshatriya, and Vaishya boys. It signifies a ‘second birth’ (Dvijati), bestowing the initiate the right to study the Vedas and participate fully in Brahmanical rituals. The ceremony involves the investiture of the sacred thread, the Yajnopavita, symbolizing purity, knowledge, and the threefold duty of life: to God, humanity, and ancestors. The Upanayana ceremony is deeply tied to Brahmacharya, the first stage of life dedicated to learning and self-discipline. It is after this ceremony that an individual is considered spiritually mature and eligible to receive Vedic teachings.

The ritual involves intricate ceremonies, prayers, and chanting of the Gayatri Mantra. The Upanayana Sanskar effectively demarcates social strata, as it was traditionally denied to Shudras and women, restricting their access to religious knowledge and spiritual authority. This exclusion reinforced the caste hierarchy and maintained the Brahmanical monopoly over sacred texts and rituals. The concept of a ‘second birth’ also draws parallels with Buddhist traditions where initiation into the Sangha signifies spiritual rebirth, leading some scholars to suggest the Brahmanical concept of Dvijati might have been influenced by or was a counter-response to Buddhism’s egalitarian ideals.

Vidyarambh Sanskar: The Beginning of Learning

The Vidyarambh Sanskar, or the ceremony of beginning education, logically follows the Upanayana Sanskar. Once an individual has undergone the sacred thread ceremony and is deemed eligible for Vedic knowledge, the Vidyarambh ceremony formally initiates them into learning. This ritual typically involves the priest guiding the student in writing their first letters or sounds, often invoking deities associated with knowledge and wisdom, like Goddess Saraswati. The ceremony marks a significant step in intellectual development, signifying readiness to absorb Vedic and scriptural teachings.

It is a declaration of commitment to scholarship and spiritual growth. However, the right to participate in this sanskar, and consequently receive formal Vedic education, was historically limited to the upper three varnas. Shudras and women were largely excluded, perpetuating a system where knowledge was an elite preserve. The Vidyarambh Sanskar, therefore, while celebrating learning, also highlights exclusionary practices within the Brahmanical system, which dictated who could access learning based on birth.

Culmination of Life: Marriage and Final Rites

Later life stages are marked by the Vivaha Sanskar (marriage) and the Antyeshti Sanskar (funeral rites). These rituals signify family unit establishment and the final passage from life, ensuring completion according to prescribed norms. The Vivaha Sanskar is a complex ceremony uniting individuals while reinforcing societal expectations and lineage continuity. The Antyeshti Sanskar closes the life cycle, with sacred fire central to dissolving the physical form.

Vivaha Sanskar: The Union of Two Souls (and Families)

The Vivaha Sanskar, or wedding ceremony, is a cornerstone of the Brahmanical life cycle, signifying the union of a man and woman to form a family and perpetuate lineage. This ritual is far more than a simple union; it’s a complex social and religious contract binding two families. The ceremony is replete with intricate rituals, prayers, and vows, emphasizing marriage’s sanctity and the couple’s responsibilities. Traditionally, the ceremony involves the sacred fire (Agni) as witness, with the couple circumambulating it, taking lifelong vows.

The concept of ‘pinda dan,’ ancestral rites, often emphasizes the need for a male heir to continue these offerings, highlighting patriarchal leanings. The elaborate nature of weddings, involving feasts and community participation, underscores marriage’s social importance. The ritualistic exchange of garlands, vermilion application, and tying of sacred knots are symbolic actions signifying the bond. While celebrated joyously, the Vivaha Sanskar also reinforces societal expectations, particularly regarding gender roles and the paramount importance of producing male progeny for continuing rituals and lineage.

Agni Sanskar: The Eternal Flame

The Agni Sanskar, or fire ritual, is integral to various Brahmanical ceremonies, including marriage. In marriage, it involves the couple taking seven steps, or pheras, around the sacred fire, symbolizing union and commitment. This fire, lit during the wedding, was traditionally meant to be maintained continuously in the household, symbolizing purity, divine presence, and continuity of spiritual practices. This ‘eternal flame’ was historically the primary source for cooking and other household needs before modern conveniences. Maintaining this sacred fire was a significant responsibility, linking daily life to the divine.

The Agni Sanskar highlights fire’s central role as a purifier and witness in Brahmanical rituals, representing the divine’s transformative power and the couple’s commitment to upholding sacred traditions. The continuation of this fire from marriage to final rites signifies the unbroken thread of life and spiritual continuity, serving as a constant reminder of sacred vows and divine presence.

Antyeshti Sanskar: The Final Journey

The Antyeshti Sanskar marks the final rite of passage in the Brahmanical tradition—the funeral ceremony. This ritual helps the soul transition peacefully from the earthly realm to the afterlife. It involves purification rites, prayers, and cremation. The sacred fire, central to Vivaha Sanskar, plays a crucial role here too, with the funeral pyre lit using the same fire maintained throughout married life. This act symbolizes the earthly journey’s culmination and the soul’s release.

The Antyeshti Sanskar is believed to alleviate suffering for the departed soul and ensure its peaceful journey. It’s a solemn occasion reinforcing beliefs in reincarnation and the soul’s continuation. Priests guide the family through this challenging period, performing rituals and offering solace. The emphasis on purification and sacred fire highlights the Brahmanical understanding of death not as an end, but as a transition, part of a larger cosmic cycle. Rituals surrounding death honor the deceased, provide closure, and ensure the departed soul’s spiritual well-being.

The Pervasive Influence and Exploitation by the Priestly Class

The detailed examination of these sanskars reveals a pervasive system of rituals touching every aspect of human life. Critics argue this elaborate framework, while seemingly offering spiritual guidance and social order, historically served the Brahmanical priestly class as a tool for control and exploitation. From conception to final rites, every significant event is mediated by priests, necessitating their involvement and fees. This pervasive presence created deep-seated dependence, making it difficult for individuals to deviate, even facing financial hardship or rational doubts. The constant need for priests for various occasions—naming ceremonies, housewarmings, career advancements, wedding arrangements—ensures their continued relevance and economic prosperity.

The Dehumanization of Women in Rituals

Brahmanical rituals, especially concerning women’s bodies and reproductive roles, have often led to their dehumanization and marginalization. The Garbhadhan Sanskar, in its modernized form as proposed by Swami Dayanand Saraswati, exemplifies this. The ritual necessitates four priests and elder male relatives witnessing and chanting overtly sexual mantras aimed at the woman’s reproductive organs. This public recitation of explicit verses, targeting the woman’s body in a context of expected procreation, is deeply humiliating and objectifying. As noted by scholars like Dr. Surendra Agyat, such public exposure and crude language would leave a woman in profound shame and psychological distress, potentially worse than that of a sex worker.

Furthermore, the Puranas and other scriptures often depict women as subordinate beings, primarily valued for bearing children, especially sons. Their bodily functions, such as menstruation, are treated with ritualistic impurity, rendering them untouchable for several days.

The Parashar Smriti, for instance, classifies women as impure during menstruation, comparing them to untouchables. This consistent portrayal of women as ritually impure, objects of procreation, and subordinate beings within the religious framework contributes to their dehumanization and reinforces patriarchal control. The emphasis on rituals over a woman’s agency and dignity highlights a deep-seated bias prioritizing tradition and priestly authority over women’s well-being and respect.

The Myth of ‘Vedic Science’ and Its Flaws

Proponents of Brahmanical traditions often claim their scriptures are repositories of ancient scientific knowledge, including advanced medical and biological understanding. However, critical scrutiny of texts like the Vedas, Manusmriti, and Yajurveda, particularly concerning sanskars like Garbhadhan, reveals practices and beliefs that are not only unscientific but demonstrably flawed and often contradictory. The supposed “science” behind determining child sex or regulating conception relies on archaic notions and lunar cycles rather than biological realities. In an era where science offers precise answers to biological questions, why do ancient rituals continue to hold such sway over fundamental human experiences like conception?

Contradictory and Unscientific Notions of Sex Determination

Brahmanical texts present bewildering, unscientific theories on sex determination. Some interpretations suggest intercourse on specific lunar nights determines the child’s sex: even-numbered nights (sam ratri) supposedly result in a male, while odd-numbered nights (vishama ratri) produce a female. This notion is baseless, as modern genetics clearly establishes sex determination by the father’s sperm (X or Y chromosome).

The lunar calendar has no bearing. Adding to confusion, texts like Manusmriti propose sex depends on the relative potency of male semen (virya) and female ovum (rajas): dominant semen yields a son; dominant ovum, a daughter; equal, an intersex or non-viable embryo. This theory is also scientifically inaccurate, ignoring complex genetic sex-determining mechanisms.

The lack of coherent, scientifically grounded understanding of reproduction highlights the speculative and mythological nature of these ancient texts. The persistence of such beliefs, often presented as divine wisdom, underscores a historical tendency to attribute natural phenomena to supernatural causes and ritualistic interventions, reinforcing the priestly class’s authority.

Misinterpretations of Ayurveda and Biological Processes

While Brahmanical scriptures cite Ayurvedic principles, their application within sanskars reveals misunderstanding or deliberate misinterpretation of biological processes. The Garbhadhan Sanskar, for example, involves specific timings and procedures for intercourse, often linked to a woman’s menstrual cycle. However, the guidelines are frequently contradictory and unscientific. Texts suggest certain menstrual days are “inauspicious” for conception, others ideal. Ironically, “auspicious” days are often when conception is biologically less likely, while “inauspicious” days are fertile periods.

Furthermore, the notion that dominant male semen leads to a son and dominant female ‘rajas’ leads to a daughter ignores the fundamental role of the Y chromosome in male offspring. The emphasis on ritualistic practices—consuming specific foods or chanting mantras—instead of understanding and respecting natural biological processes characterizes these interpretations. While Ayurveda offers valuable health insights, its integration into sanskars often legitimizes superstitious beliefs and priestly interventions rather than genuinely applying scientific principles.

The Illusion of ‘Vedic Science’ in Modern Times

The claim that Vedic scriptures contain advanced scientific knowledge is a narrative often promoted to lend Brahmanical traditions authority. However, on critical scrutiny, these claims often crumble. The so-called “Vedic science” regarding conception, sex determination, or the universe’s composition is largely based on metaphorical language, mythological narratives, and speculative philosophy, not empirical observation. For instance, the description of the human body as five elements—earth, water, fire, air, and ether (akash)—while philosophically resonant, is a simplistic cosmological model compared to modern science. ‘Akash’ as a fundamental body component lacks empirical definition.

Similarly, purported scientific explanations within Vedas often serve as allegories rather than literal facts. Interpreting these texts as direct scientific treatises is a modern phenomenon, driven by a desire to reconcile ancient traditions with contemporary science or to counter criticism by asserting Vedic knowledge’s intellectual superiority. This approach often involves selective interpretation, overlooking contradictory or non-scientific elements. The persistent assertion of ‘Vedic science’ without empirical validation serves more as a rhetorical tool than a genuine reflection of scientific discovery.

Conclusion: Moving Beyond Superstition and Exploitation

The exploration of sanskars, particularly the Garbhadhan Sanskar, reveals a complex tapestry of rituals deeply embedded in the Brahmanical tradition. While these practices are presented as essential for spiritual well-being and a prosperous life, critical analysis exposes their unscientific underpinnings, wasteful nature, and the potential for exploitation by the priestly class. Reliance on superstitious beliefs, contradictory theories, and the dehumanization of individuals, especially women, are significant concerns. The pervasive influence of these rituals has created societal dependence, hindering rational thought and perpetuating blind faith. Therefore, challenging these practices is not about discarding tradition but advocating for a more rational, equitable, and resource-conscious approach to life’s significant moments.

What You Can Do?

Understanding the historical and social context of these sanskars is the first step toward critical engagement. Encourage open discussions about the rationale behind these rituals, questioning their scientific validity and ethical implications. Promote education emphasizing critical thinking and scientific temper, empowering individuals to make informed choices rather than blindly following tradition. Support initiatives advocating for social equity and challenging caste-based discrimination, often reinforced by these sanskars. By fostering rational inquiry and promoting evidence-based practices, we can move toward a society valuing well-being, resourcefulness, and human dignity over blind adherence to outdated and exploitative rituals.

Disclaimer

This article delves into the intricacies of Brahmanical sanskars, including the Garbhadhan Sanskar. The term ‘Brahmanical system’ refers to the socio-religious framework and practices associated with the Brahmin caste in historical and traditional India. ‘Sanskar’ denotes a ritual marking a life event. ‘Priestly class’ refers to Brahmins who traditionally officiated ceremonies. ‘Dvijati’ signifies ‘twice-born,’ a status attained by upper-caste males after Upanayana Sanskar, granting them Vedic study rights. ‘Havan’ is a fire ritual. ‘Ghee’ is clarified butter. ‘Manusmriti,’ ‘Gautam Smriti,’ ‘Vyasa Smriti,’ and ‘Parashar Smriti’ are ancient Indian legal/religious texts. ‘Rigveda’ and ‘Yajurveda’ are Vedic hymns. ‘Arya Samaj’ is a Hindu reformist movement.

‘Shudra’ is the lowest of the four traditional varnas. ‘Rajas’ refers to female reproductive fluid/ovum, and ‘Virya’ to male semen. ‘Yoni’ refers to female genitalia. Discussions on specific mantras/rituals are for critical analysis and do not endorse practice. This article aims for an objective, critical perspective based on the provided context.

Read more about Ancient Indian Medicine: Beyond Common Narratives

Find out more about Unveiling the Truth: Hindu’s Ancient Science or Modern Propaganda?

Do you disagree with this article? If you have strong evidence to back up your claims, we invite you to join our live debates every Sunday, Tuesday, and Thursday on YouTube. Let’s engage in a respectful, evidence-based discussion to uncover the truth. Watch the latest debate on this topic below and share your perspective!