The Global Spread of Manuvadi Ideology: A Threat to Equality

In an increasingly interconnected world, the insidious spread of divisive ideologies poses a significant threat to the principles of equality and justice. One such ideology, rooted in ancient discriminatory practices, is the Manusmriti ideology, often referred to as Manuvad. This ideology, which advocates for a hierarchical social system based on birth, has found fertile ground in various countries, often through orchestrated campaigns by organizations masquerading as cultural representatives.

Recent events, particularly in the United Kingdom, have brought to light the sophisticated methods employed by these groups to undermine efforts aimed at achieving social equality. This analysis delves into the historical context, the deceptive tactics used, and the intellectual counter-offensives that have emerged to combat this pervasive ideology, highlighting the critical need for awareness and vigilance.

The UK Incident: A Case Study in Deception

A pivotal moment in understanding the global reach of Manusmriti ideology occurred around 2018 in the United Kingdom. At that time, the UK was considering the passage of a Single Equality Bill. This legislation aimed to consolidate existing equality laws and introduce new protections, specifically targeting discrimination based on caste.

For proponents of social justice, this bill represented a significant step towards eradicating deep-seated prejudices and ensuring equal rights for all, regardless of their social standing. However, for those who benefit from a discriminatory social hierarchy, the bill was perceived as a direct threat to their privileged position.

The Role of the Hindu Council UK and Dr. Raj Pandit Sharma

The Hindu Council UK, an organization operating within the United Kingdom, emerged as a primary antagonist to the Single Equality Bill. Leading the charge against this progressive legislation was Dr. Raj Pandit Sharma, who, by his own account and the organization’s positioning, acted as a key figurehead. Sharma, through the Hindu Council UK, actively sought to influence public opinion and policy-making by presenting a distorted narrative about the nature of the caste system in India.

His efforts were primarily focused on convincing the British intellectual and political class that the caste system was not, in fact, a system of inherited discrimination but rather a consequence of one’s actions and karma.

The ‘The Caste System’ Controversy

Dr. Raj Pandit Sharma authored a book titled ‘The Caste System,’ which became the cornerstone of his campaign. In this book, Sharma attempted to dismantle the established understanding of the caste system as a hereditary social structure. He selectively cherry-picked historical figures, both real and mythological, such as Valmiki, Shivaji, Vyas, and Tulsidas, to argue that their social standing was determined by their deeds and karma, not by their birth. This selective portrayal aimed to create an impression that the caste system was a meritocratic framework, thereby absolving it of its inherent discriminatory nature.

Distorting Historical Figures for Ideological Gain

Sharma’s strategy involved presenting a revisionist history where figures like Valmiki, who is traditionally associated with a lower social standing, were re-framed as being elevated by their ‘karma.’ Similarly, he sought to portray Shivaji Maharaj, a Maratha warrior king, not as a product of his Kshatriya lineage but as someone who achieved his status through sheer merit.

By selectively highlighting certain aspects of these figures’ lives and ignoring others, Sharma aimed to create a narrative that supported his argument that caste was fluid and determined by actions rather than birth. This selective interpretation conveniently ignored the overwhelming historical and textual evidence that points to the hereditary nature of the caste system.

Manipulating Religious Texts

Beyond selectively presenting historical figures, Sharma also resorted to manipulating religious texts. He reportedly cherry-picked verses from the Manusmriti and the Mahabharata, twisting their meanings to suit his agenda. These fragmented quotes were presented to the British intelligentsia as definitive proof that the caste system was not inherently discriminatory. T

his tactic is a classic example of how proponents of Manusmriti ideology often engage in eisegesis (the practice of interpreting a text by reading one’s own ideas, biases, or assumptions into it, rather than drawing meaning from the text itself), reading their pre-conceived notions into sacred texts rather than deriving their understanding from the texts themselves. The aim was to convince foreign audiences that the caste system was a misunderstood social order, not an oppressive one.

The Counter-Narrative: Ambedkarite Intellectualism Strikes Back

Fortunately, Sharma’s deceptive campaign did not go unchallenged. The intellectual legacy of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, and the vibrant movement he inspired, provided a formidable counter-narrative.

‘The Offspring of Caste’ by Chamanlal

In direct response to Sharma’s ‘The Caste System,’ a powerful rebuttal emerged in the form of a book titled ‘The Offspring of Caste,’ authored by the esteemed scholar Chamanlal. Despite facing health challenges at the time, Chamanlal meticulously deconstructed Sharma’s arguments, presenting irrefutable evidence to expose the falsehoods and manipulations. His work served as a crucial intellectual weapon, providing factual ammunition to counter the Manuvadi narrative being propagated abroad.

Debunking Sharma’s Claims with Factual Evidence

Chamanlal’s book systematically dismantled Sharma’s claims by presenting authentic interpretations of historical events and religious texts. He highlighted how figures like Valmiki, Vyas, and Tulsidas were indeed associated with specific social backgrounds, and that their elevation, if any, was often in defiance of, or in spite of, the prevailing social order, not because of its inherent flexibility. He meticulously exposed how Sharma had twisted scriptures like the Manusmriti and the Mahabharata to support a pre-determined conclusion, ignoring the broader context and the discriminatory implications of many of its verses.

The Influence of Ambedkar’s Philosophy

Chamanlal’s work was deeply rooted in the philosophical framework established by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar. Ambedkar’s extensive research and critique of the caste system had already laid bare its hereditary and oppressive nature. Chamanlal built upon this foundation, presenting the evidence in a manner that was accessible and persuasive to an international audience. He emphasized Ambedkar’s key arguments, such as the fact that caste is not merely a division of labor but a system of graded inequality, with endogamy and untouchability being its defining characteristics. The intellectual rigor of his response provided a stark contrast to the selective and manipulative approach of Sharma.

Dr. Surendra Gyan’s Scholarly Contribution

Adding further weight to the counter-narrative was the scholarly work of Dr. Surendra Agyat, an internationally recognized scholar of Sanskrit and Indian culture. Recognizing the gravity of the misinformation being spread, Dr. Agyat penned a book titled ‘Bhaad me Jae Jati Janmana Varna Karma na‘ (May Caste Go, Whether by Birth or by Karma). This work provided a comprehensive analysis of the caste system, reinforcing the understanding that regardless of whether caste is viewed through the lens of birth or karma, its fundamental existence is problematic and antithetical to human dignity.

Challenging the ‘Karma’ Argument Head-On

Dr. Agyat’s book directly confronted the argument that caste is determined by karma. He meticulously examined the scriptural basis for such claims, particularly those found in the Bhagavad Gita. By analyzing the original Sanskrit verses and their historical context, he demonstrated how the interpretation of ‘guna’ (quality) and ‘karma’ (action) had been deliberately manipulated over centuries to justify a hereditary caste system. He argued that the concept of karma, when divorced from its spiritual essence and weaponized to uphold social hierarchies, becomes a tool of oppression rather than a path to spiritual liberation.

The Immutability of Birth and Caste

A significant portion of Dr. Agyat’s work focused on proving the inherent connection between birth and caste in traditional Indian society. He cited numerous examples from ancient texts, including the Manusmriti, to illustrate how names, surnames, and social privileges were assigned at birth, unequivocally demonstrating the hereditary nature of the caste system. His research provided concrete evidence that contradicted Sharma’s assertions, solidifying the understanding that caste was, and in many ways continues to be, a birth-based social stratification.

Scriptural Analysis: Unraveling the Truth

To further dismantle the Manuvadi narrative, a close examination of key religious and historical texts is essential. These texts, when analyzed without the distortions introduced by ideologues like Sharma, reveal the true nature of the caste system and its origins.

The Manusmriti: A Foundation of Caste Hierarchy

The Manusmriti, often cited as a foundational text for Hindu law and social conduct, is replete with verses that explicitly establish a hereditary caste system. From the very naming conventions to the assignment of duties and punishments, the text clearly delineates social roles based on birth.

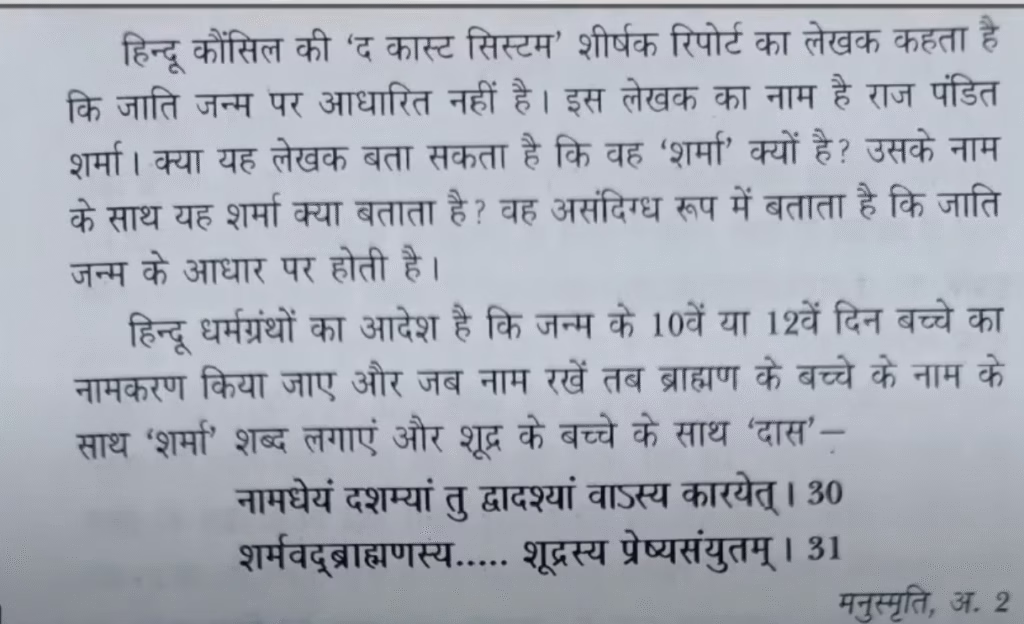

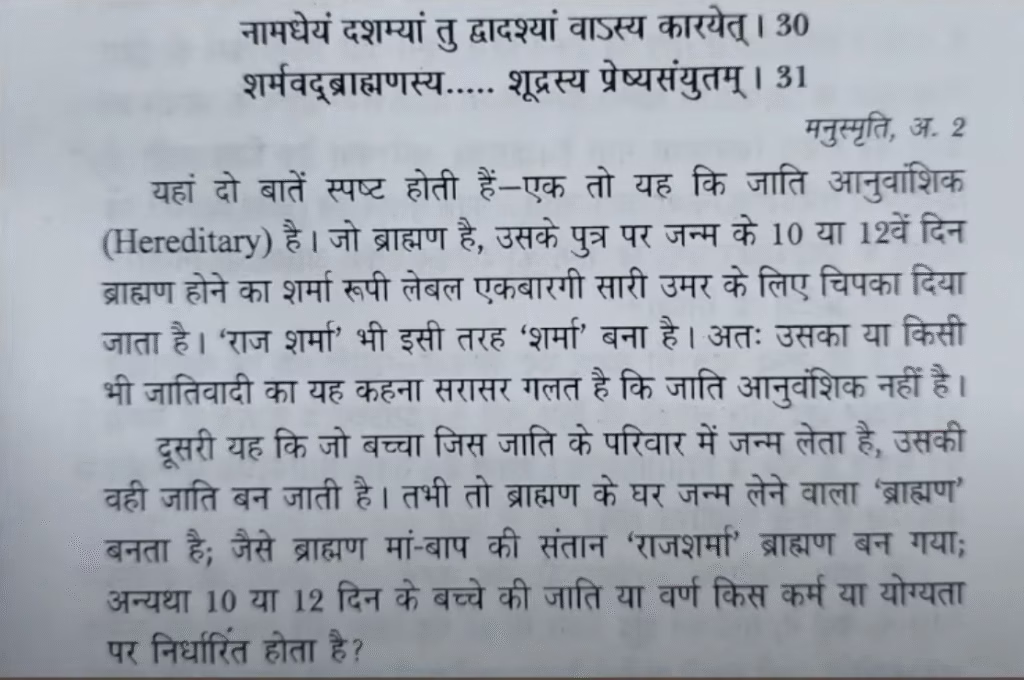

Surnames and Naming Conventions

The Manusmriti, in its second chapter (Adhyaya 2), outlines naming conventions that are directly linked to social class. It specifies that the names of Brahmins should be indicative of ‘prosperity’ (e.g., Sharma), Kshatriyas of ‘protection’ (e.g., Varma), Vaishyas of ‘commerce’ (e.g., Gupta), and Shudras of ‘service’ (e.g., Das).

This clearly indicates that a person’s social identity, including their surname, was determined at birth, not by their actions. If caste is truly determined by karma, how can one be born with a surname like ‘Sharma’?

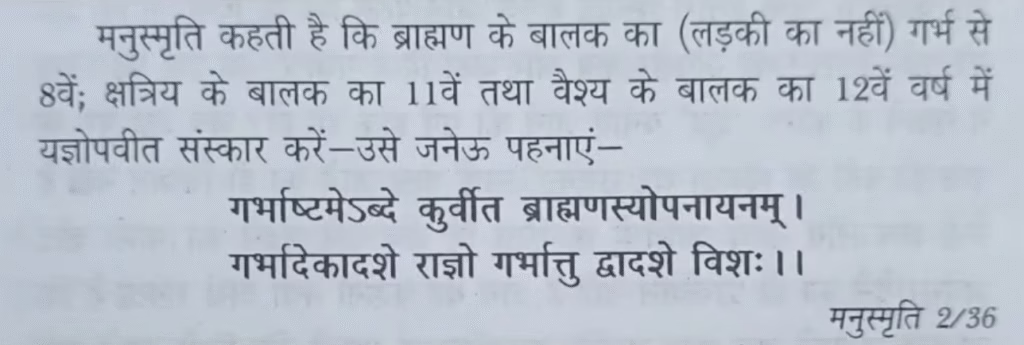

The Upanayana Sanskar and Educational Rights

The Manusmriti also dictates the ‘Upanayana’ or sacred thread ceremony, a rite of passage that traditionally marked the eligibility for formal education. The age at which this ceremony could be performed varied according to caste: the eighth year for Brahmins, the eleventh for Kshatriyas, and the twelfth for Vaishyas. Crucially, Shudras and women were excluded from this rite and, consequently, from formal Vedic education.

This exclusion was not based on any perceived lack of ability or karma but solely on their birth status. The Manusmriti explicitly states that the Upanayana ceremony for women is their marriage, thereby denying them educational rights based on their gender and social standing.

The Denial of Education to Women and Shudras

The discriminatory practices extended to the denial of education to women and Shudras. While the Manusmriti might have implicitly acknowledged the potential for women to acquire knowledge, it fundamentally relegated their role to domestic duties and service to their husbands. The text states that a woman’s marriage is her Upanayana, and serving her husband is akin to studying the Vedas.

This serves as clear evidence that formal education and access to sacred knowledge were systematically denied to women and Shudras based on their birth, directly contradicting the claims of Manuvadi ideologues.

The Bhagavad Gita: Misinterpretations and Manipulations

The Bhagavad Gita, revered as a spiritual discourse, has also been a subject of Manusmriti ideology of manipulation. The famous verse, ‘Chaturvarnyam Maya Srishtam Guna Karma Vibhagasah’ (Chapter 4, Verse 13), is often cited to claim that the fourfold varna system was created by God based on qualities and actions.

The Myth of ‘Guna’ and ‘Karma’ as Determinants

Proponents of Manusmriti ideology, like Sharma, exploit this verse to argue that caste is not based on birth but on an individual’s inherent qualities (‘guna’) and actions (‘karma’). However, a deeper analysis of the Gita and its commentaries reveals a different story. The text itself describes three ‘gunas’: Sattva (purity, goodness), Rajas (passion, activity), and Tamas (ignorance, inertia).

The Shankara Commentary and the ‘Permutation Combination’

The problem with the ‘guna’ and ‘karma’ argument becomes apparent when one considers the subsequent development of the caste system. If qualities and actions were the sole determinants, then individuals displaying ‘Sattvic’ qualities should have been recognized as Brahmins, regardless of their birth. However, history shows that this was not the case. Scholars like Adi Shankaracharya, in his commentary on the Gita, attempted to reconcile the ‘guna’ and ‘karma’ argument with the existing social order.

Later commentaries, such as those by Madhvacharya, further complicated this by introducing complex permutations and combinations of the gunas to explain the emergence of the four varnas, including the Shudra. These attempts were clearly post-hoc rationalizations to legitimize a system that was already entrenched by birth.

The Case of Krishna and Ravana

The Gita’s own narrative also presents inconsistencies with the ‘guna’ and ‘karma’ argument. Lord Krishna, the divine charioteer and speaker of the Gita, was a Kshatriya by birth. Despite his profound wisdom and role in establishing dharma, he remained a Kshatriya.

Similarly, Ravana, a learned scholar and devout devotee of Shiva, was a Brahmin by birth but often acted in ways that were considered ‘Tamasic’ or ‘Rajasic.’ If karma and guna were the sole determinants, Krishna should have been a Brahmin, and Ravana’s actions should have disqualified him from his Brahmin status. The fact that their birth status remained unchanged, despite their actions and qualities, highlights the primacy of birth in defining one’s varna in the societal understanding of the time.

The Chandogya Upanishad: Birth and Rebirth

Even texts like the Chandogya Upanishad, often lauded for their philosophical depth, contain passages that, when analyzed critically, reinforce the idea of birth-based social stratification, especially when considered alongside the concept of rebirth.

The Cycle of Rebirth and Social Destiny

The Chandogya Upanishad (Chapter 5, Section 10, Verse 7) states that those who perform good deeds and have good conduct attain a Brahmana, Kshatriya, or Vaishya womb. Conversely, those with evil deeds and bad conduct attain a womb of dogs, pigs, or Chandals. While this verse discusses the concept of rebirth based on karma, it implicitly links one’s next birth to a specific social category or ‘yoni’ (womb/species). If rebirth is accepted, then the ‘yoni’ one is born into in this life is a consequence of past actions.

However, since the concept of past lives is unverifiable, this becomes a justification for the existing social hierarchy. The Upanishad essentially states that your birth into a particular social stratum is a consequence of your past karma, thus reinforcing the immutability of social standing from one life to the next, making it effectively birth-based.

The Upanishadic Justification for Social Hierarchy

The Upanishadic verses, therefore, serve to provide a cosmological justification for the social hierarchy. They suggest that one’s position in society is divinely ordained, a result of karmic retribution or reward from previous lives. This narrative effectively closes the door on social mobility and reinforces the idea that one’s birth determines their destiny. This philosophical underpinning was crucial for the Manuvadi system to maintain its legitimacy and deter any challenge to the established social order.

The Manipulative Tactics of Modern Manusmriti ideology

The ideological descendants of Manu continue to employ sophisticated tactics to spread their narrative, particularly in diaspora communities and in international forums. Their goal is to create confusion and to derail efforts towards social justice.

Twisting the Narrative on Shivaji Maharaj

The reinterpretation of historical figures like Shivaji Maharaj is a prime example of this manipulation. Shivaji, a revered Maratha warrior and king, is often presented as a champion of Hindutva. However, historical accounts reveal the complex relationship he had with the Brahminical establishment of his time.

The High Cost of Brahminical Endorsement

Historical records, such as those by historian Swami Dharmanand Kosambi, indicate that Shivaji had to spend considerable wealth to gain the acceptance and legitimacy from the Brahmin priestly class for his coronation. Thousands of Brahmins were reportedly engaged for months, receiving lavish hospitality and financial compensation.

This immense expenditure was necessary because, according to the prevailing Brahminical norms, Shivaji, being from a non-Kshatriya lineage (often identified as ‘Kurmi’ or ‘Kunbi,’ agricultural castes), was not considered eligible for coronation as a king under traditional Shastric law. The Brahmins created a fabricated genealogy for him, linking him to Rajput lineage, to legitimize his rule, charging exorbitant fees for this service.

The Exclusion of Shudras from Vedic Rites

The fact that Brahmins initially refused to perform Shivaji’s coronation using Vedic rites underscores the rigid adherence to birth-based caste rules. Shivaji, despite his military prowess and establishment of a kingdom, was denied the status of a Kshatriya king by the very people who now claim him as a symbol of Hindu unity.

This historical fact directly contradicts the modern Manusmriti ideology narrative that caste is determined by karma or merit. It demonstrates that even a figure of Shivaji’s stature had to navigate and, to some extent, appease the Brahminical power structure, which was firmly rooted in birthright.

Tulsidas and the Perpetuation of Casteism

The popularization of Tulsidas’s ‘Ramcharitmanas’ has also been instrumental in perpetuating casteist sentiments, even in modern times.

‘Das’ as a Suffix for Shudras

The very name ‘Tulsidas’ carries significance. The suffix ‘Das’ in Sanskrit means ‘servant’ or ‘slave’ and was traditionally used for Shudras. While figures like Kabir Das and Raidas, who were also from lower social strata, achieved great spiritual recognition, Tulsidas, despite being a poet and philosopher, was accepted into the Brahmanical fold. This acceptance was not due to his merit alone but because his writings, particularly the ‘Ramcharitmanas,’ actively reinforced the existing caste hierarchy and vilified lower castes.

Vilification of Lower Castes in Ramcharitmanas

In the ‘Ramcharitmanas,’ Tulsidas consistently denigrates lower castes. He describes Shudras who engage in religious discourse or question Brahmins as being arrogant and deserving of punishment. Tulsidas also lists various artisan and trading communities (like ‘Teli’ – oil pressers, ‘Kalwar’ – liquor sellers) as being equivalent to butchers and, by extension, lower than Brahmins.

He further asserts that even if these individuals attain wealth or status, they are inherently inferior and should not be respected. These passages directly promote the idea that birth determines one’s social worth and that lower castes are inherently impure and undeserving of respect or equality.

This aligns perfectly with the Manuvadi agenda that Dr. Raj Pandit Sharma was promoting abroad.

The Hypocrisy of Caste Opponents

The irony is that many who ardently oppose caste discrimination today still hold the ‘Ramcharitmanas’ in high esteem. Tulsidas’s writings, which explicitly advocate for caste hierarchy, are widely circulated and revered. This creates a cognitive dissonance where individuals condemn casteism in principle but passively endorse texts that perpetuate it. The continued veneration of such texts serves to legitimize the very ideology that needs to be dismantled.

The Case of Valmiki and Vyas: Birth vs. Karma Revisited

Sharma’s attempt to reframe figures like Valmiki and Vyas as examples of ‘karma-based’ elevation is also a gross misrepresentation of historical and textual evidence.

Valmiki: A Brahmin by Birth, Not by Karma

While Valmiki is revered as the author of the Ramayana, his origins are widely understood within Hindu tradition as being from a lower social stratum. However, some narratives suggest he was a Brahmin who fell from grace and later reformed. The text cited is (Ramayana’s Uttara Kanda, 96.19) and Adhyatma Ramayana clearly state that Valmiki was the tenth son of Prajapati (a lineage associated with Brahma) but lived among the Bhils (a tribal community) and engaged in their activities. Later, in the same texts, when referring to his Brahminical lineage, it is stated that he was born a Brahmin.

This indicates that his social identity was always considered Brahmin by birth, irrespective of his association with the Bhils. The notion that his ‘karma’ as a highway robber (a popular legend) led him to become a Brahmin sage is a later embellishment, designed to fit the ‘karma’ narrative, rather than historical fact.

Vyas: A Product of Brahminical and Kshatriya Lineage

Similarly, the assertion that Vyas, the compiler of the Mahabharata, was elevated by his mother Satyavati’s ‘karma’ is misleading.

The Mahabharata (Adi Parva, Chapter 63) itself details the birth of Vyas. Satyavati, a princess, was given to a fisherman (Mallah) due to a fishy odor emanating from her body. However, she was the daughter of a king. When the sage Parashara encountered her, he used his spiritual powers to create an island and an enclosure of reeds, allowing them to be together discreetly. He also blessed Satyavati with a boon that the fishy odor would disappear and that she would remain a virgin even after childbirth.

Satyavati’s son, Vyas, was born on an island and was a product of a Brahmin sage (Parashara) and a Kshatriya princess (Satyavati). Therefore, Vyas was not solely a product of his mother’s ‘karma’ but a combination of Brahminical and Kshatriya lineage. The narrative of his birth is complex and does not support the simplistic ‘karma determines caste’ argument.

The Fight for Equality: A Continuing Struggle

The efforts by individuals like Dr. Raj Pandit Sharma highlight the ongoing struggle to uphold principles of equality against ideologies that seek to perpetuate discrimination. The counter-narratives provided by scholars like Chamanlal and Dr. Surendra Agyat are crucial in this fight. This intellectual counter-offensive is vital for supporting anti-caste activism globally.

Challenging the ‘Meritocracy’ Myth

The emphasis on ‘merit’ and ‘qualification’ by opponents of affirmative action, like Sharma, is often a smokescreen for their desire to maintain existing privileges. The historical record, as evidenced by the cases of Shivaji and figures like Valmiki and Vyas, shows that ‘merit’ has often been subordinate to birth in the traditional Indian social order.

The very system that denied education and opportunities to vast segments of the population based on their birth cannot suddenly claim to champion meritocracy when its privileges are being challenged. Sharma’s tactic is akin to claiming a skyscraper is built on merit alone, ignoring the foundations laid by architects and engineers who designed it, and the laborers who toiled to construct it. He focuses only on the ‘occupant’ and their perceived success, not the systemic structure that determined their position.

The Enduring Legacy of Discrimination

The persistence of Manuvadi ideology, even in the 21st century and across international borders, underscores the deep-rooted nature of caste discrimination. It demonstrates that the struggle for social justice is not merely about changing laws but also about challenging deeply ingrained beliefs and dismantling the systems that uphold them. The systematic distortion of history and religious texts serves as a stark reminder of the continuous effort required to ensure that equality and human dignity prevail.

What You Can Do?

It is imperative for individuals to critically engage with historical and religious texts, relying on scholarly interpretations rather than ideologically driven narratives. Supporting and amplifying the voices of Ambedkarite scholars and activists who are working to expose these distortions is crucial. Educate yourself and others about the true nature of the caste system and its historical manifestations. By fostering critical thinking and promoting factual accuracy, we can collectively counter the spread of divisive ideologies and work towards a more just and equitable society.

If you want to read further, please order the book and support DBA Business. Here’s the link

Read more about Manusmriti: Why Brahmins Should Also Burn it?

Unmasking Manusmriti: How Manu Impacted Kshatriyas & Society

Oppression in Manusmriti: Exposing Vaishya Caste Plight

Do you disagree with this article? If you have strong evidence to back up your claims, we invite you to join our live debates every Sunday, Tuesday, and Thursday on YouTube. Let’s engage in a respectful, evidence-based discussion to uncover the truth. Watch the latest debate on this topic below and share your perspective!