Is vegetarianism merely a personal dietary choice in India, or does it function as a weapon to perpetuate caste-based discrimination? This article fearlessly delves into the intricate relationship between vegetarianism and casteism in Indian society, exploring how dietary practices are sometimes weaponized against marginalized communities.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Malnutrition and Hunger in India

- Global Hunger Index and India’s Ranking

- National Food Security Act and Persistent Hunger

- Child Mortality Due to Malnutrition

- Stunted Growth and Wasting

- Affordability of Healthy Diets

- Vegetarianism as a Weapon of Casteism

- Discriminatory Practices and Dietary Habits

- The Deep-Rooted Casteism in Dietary Habits

- Conclusion

Introduction

In India, food transcends mere sustenance; it often becomes a powerful marker of social identity and hierarchy. Globally, people recognize vegetarianism as a dietary preference. However, in India, it is frequently intertwined with caste dynamics. This article examines whether vegetarianism is exploited as a tool to perpetuate discrimination against marginalized communities, particularly Scheduled Castes (SC), Scheduled Tribes (ST), and Other Backward Classes (OBC), collectively known as Bahujan. We will explore the complex interplay between food habits, social status, and historical injustices, questioning if the promotion of vegetarianism in India serves a more insidious purpose than just ethical eating. Is using vegetarianism as a marker of social status any different from using skin color? Both create artificial hierarchies.

Malnutrition and Hunger in India

Before examining the weaponization of vegetarianism, it is crucial to understand the underlying issues of malnutrition and hunger that plague significant portions of the Indian population. These issues disproportionately affect marginalized communities, making them more vulnerable to dietary coercion.

Extent of Malnutrition

India faces a severe malnutrition crisis, with millions lacking access to adequate nutrition. A July 2024 report highlighted that India has become the ‘malnutrition capital‘ of the world

Malnutrition, or malnourishment, results from deficiencies or excesses in nutrient intake, leading to impaired physical and mental development.

According to recent data, approximately 19.5 crore people in India are victims of malnutrition, the highest number in the world

This means a significant portion of the population does not receive sufficient food or the necessary nutrients for healthy development. This problem is particularly prevalent among Bahujan communities.

Global Food Security Report

This financial constraint limits access to nutritious food, perpetuating a cycle of poor health and stunted development.

Anemia in Women

The situation is especially dire for women, with over half of Indian women (53%) suffering from anemia.

This deficiency, more prevalent in South Asia and worldwide, impairs cognitive and physical functions, making them more susceptible to various health issues. The lack of iron and essential nutrients hinders their ability to make informed decisions and resist social pressures.

Global Hunger Index and India’s Ranking

India’s performance on the Global Hunger Index (GHI) further underscores the severity of the crisis. In the 2023 report, India ranked 111th out of 125 countries, indicating a critical level of hunger

Only 14 countries fared worse than India, including some of its neighbors like Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, showcasing the dire state of food security.

National Food Security Act and Persistent Hunger

Despite the implementation of the National Food Security Act in 2013, about 19 crore people in India still sleep hungry every night. These individuals lack adequate nutrition and essential nutrients, highlighting the limitations and gaps in the existing food distribution systems. If food is meant to nourish, why does it so often divide in India?

Child Mortality Due to Malnutrition

Malnutrition significantly contributed to child mortality in India. In 2019-20, malnutrition caused 69% of child deaths in India

Additionally, about 38% of India’s population suffers from long-term malnutrition, reflecting a chronic failure to address dietary needs.

Stunted Growth and Wasting

Stunted growth, characterized by reduced height for age, is a visible manifestation of chronic malnutrition. According to the GHI, a significant percentage of Indian children under five suffer from wasting (low weight for height), with figures around 19.3%

This condition impacts their physical and cognitive development, perpetuating a cycle of disadvantage.

Affordability of Healthy Diets

The high cost of nutritious food further exacerbates malnutrition. About 56% of Indians cannot afford a balanced diet, making access to healthy food an insurmountable challenge for many

Rising unemployment and inflation have compounded these issues, limiting the availability of essential nutrients.

Vegetarianism as a Weapon of Casteism

Against this backdrop of widespread malnutrition, the promotion of vegetarianism takes on a more sinister dimension. It is argued that certain groups weaponize vegetarianism to marginalize and discriminate against Dalits, OBCs, and minorities, using dietary habits to enforce social hierarchies and communal hatred.

Vegetarianism and Social Division

The emphasis on vegetarianism in India often serves to create divisions within society. It is used as a tool to enforce purity and impurity, with vegetarianism being equated to higher social status. This notion leads to the exclusion and discrimination against those who consume meat, especially Muslims and Dalits

The subtle message is that non-vegetarians are somehow less pure or less deserving of respect.

The Myth of a Vegetarianism India

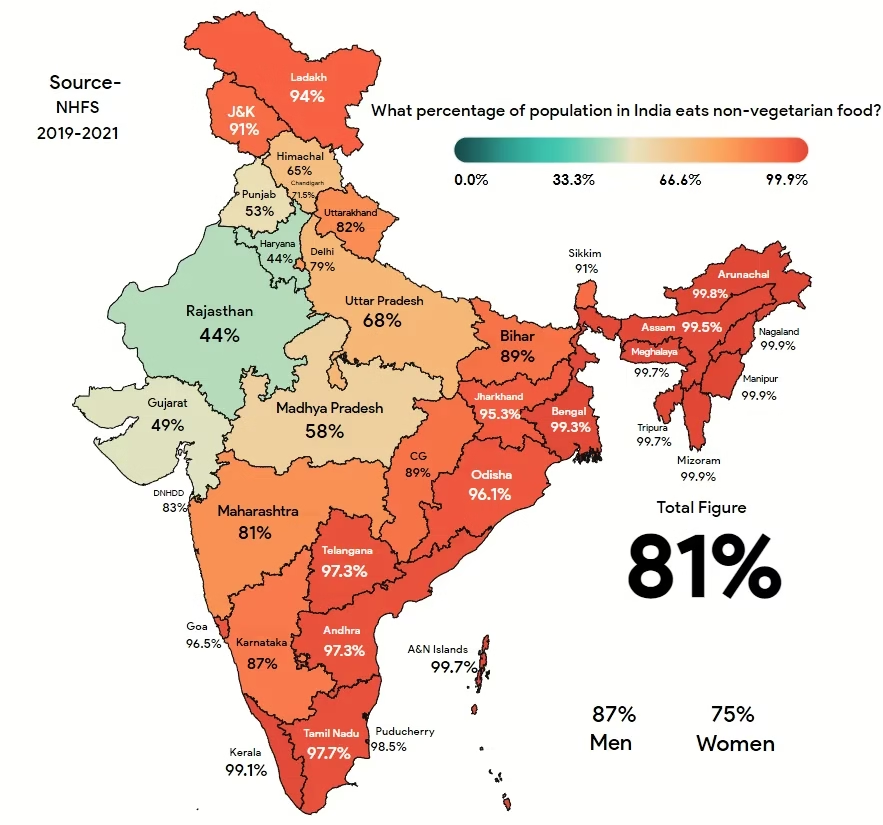

Despite the global perception of India as a predominantly vegetarian nation, data indicates otherwise. India ranks low among countries with high meat consumption, disproving the widely held belief. Reports suggest that a significant majority of the population, around 81%, is non-vegetarian

This reality challenges the narrative promoted by certain groups who seek to impose vegetarianism as the national norm.

National Family Health Survey Data

Data from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) further supports the claim that non-vegetarianism is widespread. The survey reveals that a substantial percentage of men and women across different religious groups consume non-vegetarian food

For instance, 87% of men and 75% of women consume non-vegetarian food regularly, undermining the stereotype of a wholly vegetarian population as shown in above image.

Discriminatory Practices and Dietary Habits

The promotion of vegetarianism often leads to tangible discriminatory practices affecting housing, social interactions, and access to resources. These practices highlight how dietary habits are used to reinforce caste and communal divides.

Preference for Vegetarian Tenants

One common form of discrimination is the preference for vegetarian tenants. Many landlords, particularly in urban areas, refuse to rent properties to individuals who consume meat. This practice effectively excludes non-vegetarians, particularly Muslims and Dalits, from accessing housing opportunities.

Distancing from Meat-Eaters

Beyond housing, social distancing based on dietary preferences is also prevalent. Studies indicate that a significant percentage of vegetarians prefer not to dine at restaurants serving both vegetarian and non-vegetarian options

.This segregation reinforces social hierarchies and limits interactions between different communities.

The Deep-Rooted Casteism in Dietary Habits

The link between dietary habits and casteism is deeply entrenched in Indian society. As noted by various scholars, vegetarianism in India is less about animal love and more about maintaining caste-based hierarchies. This is supported by the fact that while certain animals, like cows, are revered, others are neglected and mistreated

The selective compassion towards animals exposes the underlying caste-based motives perpetuated by Savarna groups.

A quotation from Gandhi illustrates the deep-seated biases. Gandhi, a power figure, once stated that he would rather die than consume beef or mutton, highlighting a cultural and social bias against meat consumption

In October, the Samajwadi Party government in Uttar Pradesh backed spiritual leader Ramaraju Mahanthi’s vegetarian campaign. For Mahanthi, those who consume non-vegetarian food are demons. He hopes to make such people shed their demon values.

While most Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Other Backward Classes are non-vegetarians, state governments find it difficult to even provide eggs for the school mid-day meal scheme for deprived children. The Karnataka government is currently facing opposition from vegetarian communities over its plan to introduce eggs in mid-day meals, based on choice. The plan has been in the works for a few years now but could not be implemented because of the resistance.

Given that the majority of Hindus are not vegetarian, how and why is the democratic state anxious over a non-vegetarian diet, even eggs?

The current reality is that most Indians are not vegetarian; it is a tool of caste superiority, which was initially for economic reasons and currently for social stratification. Savarna groups reinforce these views by promoting the superiority of vegetarianism, by supporting animal shelters specifically for cows, and by using existing and new online social platforms to proliferate such discriminations. This can be addressed by more compassion, less othering and a more balanced approach to living a healthy life.

Conclusion

While people respect vegetarianism as a dietary choice globally, its implications in India are complex and often discriminatory. Certain groups exploit it to enforce caste-based hierarchies, marginalize communities, and perpetuate social divisions. Addressing the root causes of malnutrition and challenging discriminatory practices are crucial steps toward creating a more equitable and inclusive society. Food should nourish and unite, not divide and oppress.

Educate yourself and others about the intersection of caste and dietary practices. Support initiatives that promote food security and challenge discriminatory norms. Advocate for policies that ensure equitable access to nutritious food for all.

Disclaimer

This article discusses sensitive topics related to caste and dietary practices in India. The following terms are used with specific contextual implications:

- Brahmin/Brahminism: Implies the ideology and social hierarchy associated with the Brahmin caste, not necessarily all individuals belonging to the Brahmin community.

- Dalit: Refers to historically marginalized communities, also known as Scheduled Castes (SC).

- OBC: Refers to Other Backward Classes, a collection of castes recognized as socially and educationally disadvantaged.

- Savarna: Refers to the upper castes in the traditional Hindu caste system.

- Bahujan: Refers to the majority population comprising SC, ST, and OBC communities.

Read More about Supreme Court Decisions and their impact on Bahujan Rights.

Find out more about the SC ST Act.

Read if a religious person can stay neutral in Positions of Power.

Do you disagree with this article? If you have strong evidence to back your claims, we invite you to join our live debates every Sunday, Tuesday, and Thursday on YouTube. Let’s engage in a respectful, evidence-based discussion to uncover the truth. Watch the latest debate on this topic below and share your perspective!