Unraveling the Mahabharata: Myth vs. Historical Claims

The epic tales of the Mahabharata have long been a cornerstone of Indian culture and identity. For many, its narratives are not merely stories but historical accounts passed down through generations, shaping their understanding of lineage and ancestry. However, a critical examination of the text, particularly concerning the origins of its prominent characters and dynasties, reveals a complex tapestry woven with mythological elements and societal constructs that challenge conventional historical interpretations.

This exploration delves into the intricate genealogies and practices described within the Mahabharata, particularly focusing on the concept of ‘niyoga’, and how these narratives might have been shaped by the socio-cultural and religious milieu of the time they were compiled. The intention is to provide a rational perspective, encouraging readers to question and analyze the information presented, moving beyond blind acceptance towards a more informed understanding of this ancient epic.

Table of Contents:

- The Strategic Weaving of Myth and History

- Literary Creations vs. Historical Records

- The Myth of Kshatriya Purity and 'Niyoga'

- The 'Niyoga' Practice: Procreation in the Mahabharata

- The 'Abhir' and the Yadavas: A Question of Identity

- The Birth of the Pandavas: Divine Intervention and 'Niyoga'

- The Unnatural Births of the Kauravas

- Conclusion: Re-evaluating the Mahabharata for Historical Truth

- What You Can Do?

The Strategic Weaving of Myth and History

When narratives are shrouded in ambiguity, there often arises a deliberate attempt to present fictional accounts as historical facts. This strategy typically aims to foster a sense of connection and belonging among the populace. By associating individuals with heroic figures, mythical ancestors, or a glorious past, the narrative gains emotional resonance and wider acceptance.

This is particularly potent for communities that have historically faced marginalization or a lack of recognition, as they are naturally drawn to narratives that offer a sense of pride and validation.

The Mahabharata, in this context, can be seen as a repository of such narratives, where certain storylines and genealogies may have been constructed to fulfill specific social and ideological objectives. The desire for honor and a sense of belonging can lead people to readily embrace these tales, sometimes leading them to believe they are direct descendants of these celebrated characters – a phenomenon akin to being ‘taken for a ride’ by history.

Literary Creations vs. Historical Records

India boasts a rich history of poetic compositions, many intricately linked with historical events. A notable example is the ‘Buddhacharita’, attributed to Ashvaghosha. While the author himself admitted to incorporating certain embellishments for poetic effect, the work was initially grounded in historical events concerning the Buddha.

However, by the seventh century CE, the influence of Buddhism began to wane in India. Subsequently, narratives like the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, which were entirely fictional in their core, were presented as historical fact.

This shift in emphasis is significant. While Buddhacharita focused on a historical figure with acknowledged creative liberties, the presentation of the Mahabharata and Ramayana as historical fact served a different purpose, potentially to fill a perceived void or establish a new ideological framework. The selective promotion of these epics over earlier historical accounts raises questions about the conscious construction of historical narratives to suit particular agendas.

The Allure of Lineage: Connecting with the Divine and the Heroic

The Mahabharata presents intricate family trees that many individuals connect with to establish their lineage. For instance, some people trace their ancestry to the Yaduvansh (Yadu dynasty) or the Kauravs and Pandavs. This desire to connect with powerful or divine figures stems from a deep-seated human need for identity and belonging. The text itself highlights the lineage of Yadu and Puru, sons of Yayati, and the complexities within their family.

Puru’s lineage continued, while Yadu was cursed by his father. The narrative invites readers to explore these familial connections, often leading them to identify with characters like Arjuna or Krishna. This identification is further amplified when characters are presented as divine or semi-divine, such as Krishna, who is revered as an avatar of Vishnu.

The text also points out societal dynamics where Brahmins, typically considered superior, are depicted bowing to Kshatriyas like Krishna, a portrayal that may have served to reinforce certain social hierarchies or to challenge existing ones, depending on the interpretation.

Manu Smriti and the Caste System

The Manu Smriti, a foundational text in Hindu law and social conduct, contains verses that outline social interactions and hierarchical relationships. For instance, it states that a hundred-year-old Kshatriya should touch the feet of an eleven-year-old Brahmin. However, the Mahabharata’s portrayal of Krishna, a Brahmin by birth and a Kshatriya by profession, interacting with and offering wisdom to Brahmins, appears to create a paradox.

Does this suggest that lineage is more about perception and influence than strict adherence to birth? The text suggests that this seemingly contradictory depiction might lead people to claim a divine lineage, thereby elevating their social standing.

The narrative highlights that claiming descent from Krishna or Rama, or any revered figure, could lead to more favorable social perception, similar to how certain families in Arab societies are respected due to their lineage from Prophet Muhammad. However, the text critically questions such claims, especially when they are made by individuals who may not even be able to comprehend the Sanskrit texts that form the basis of these traditions, suggesting a superficial adoption of lineage without genuine understanding.

The Myth of Kshatriya Purity and ‘Niyoga’

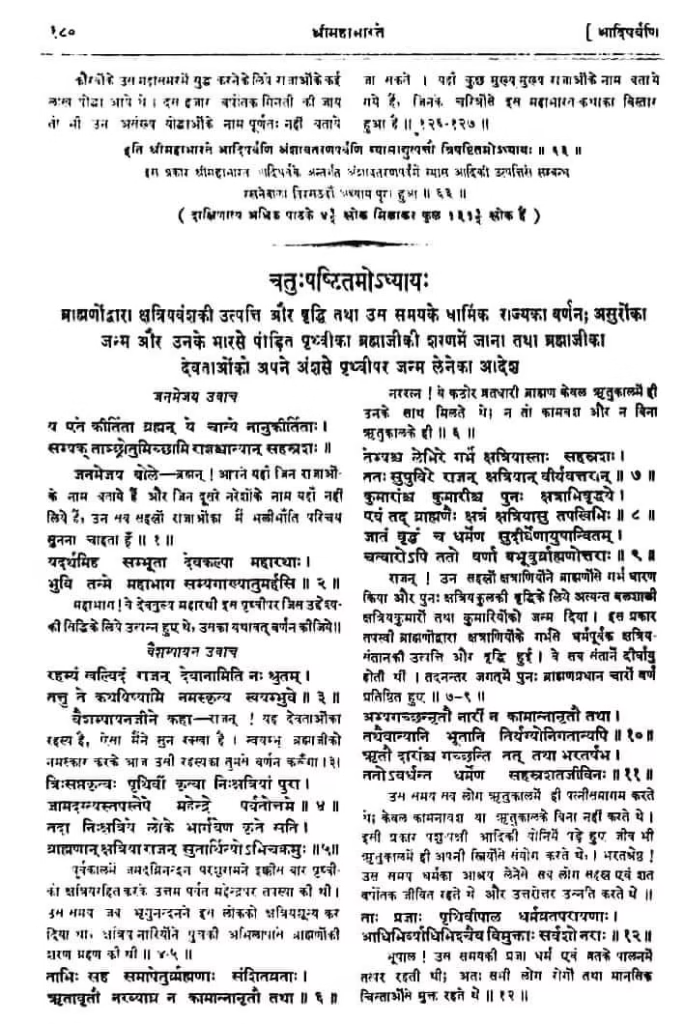

A significant aspect of the Mahabharata’s genealogical discussions revolves around the concept of ‘niyoga’, a practice where a woman, usually widowed, could have children with a designated man (often a Brahmin or a close relative) to continue the family line. The text, particularly in the Adi Parva (Chapter 64, verses 5, 7-9, and Chapter 75, verses 1-2), describes how, after Parashurama annihilated the Kshatriya race 21 times, Kshatriya women sought refuge with Brahmins to conceive children through ‘niyoga’. This suggests that the current Kshatriya lineage, according to the Mahabharata, could be traced back to Brahmins.

This is a crucial point for those who identify as Kshatriyas based on the epic. The narrative implies that the continuation of the Kshatriya line was facilitated by Brahmins, raising critical questions about the purity of bloodlines and the social implications of such practices. The text further elaborates on the lineage from Manu, stating that both Brahmins and Kshatriyas originated from him, reinforcing the idea of an interconnectedness and potential shared ancestry between the two varnas, with Kshatriyas having a connection to the Brahminical lineage.

The Lineage of Puru and Yadu: A Complex Beginning

The Mahabharata details the lineage stemming from Manu, the progenitor of mankind. Manu’s son was Ikshvaku, from whom the Suryavansh originated. The text also mentions the Chandravansh (Lunar Dynasty). It states that the lineage of Manu led to the creation of Brahmins, Kshatriyas, and all other human races. This establishes a fundamental connection between the varnas, with the Kshatriya varna being directly linked to the Brahminical lineage. The narrative traces ancestry through Manu’s 50 sons, including Puru, who was obedient to his father Yayati. The story of Yayati’s curse on Yadu, his elder son, is also recounted. Puru’s lineage continued, leading to figures like Nahusha and his son Yayati.

The text highlights that Nahusha was advised by Sanat Kumar from Brahmaloka not to oppress Brahmins, indicating past conflicts or tensions between Kshatriya rulers and the priestly class. The narrative also touches upon the tyrannical reign of King Nahusha, who imposed taxes on sages, drawing a parallel, albeit anachronistic, with historical practices like the ‘jaziya’ tax imposed by rulers on non-Muslims. This comparison, while perhaps intended to illustrate unjust taxation, also serves to highlight the author’s perspective on power dynamics and the treatment of religious figures by rulers.

The ‘Niyoga’ Practice: Procreation in the Mahabharata

The practice of ‘niyoga’ is a recurring theme in the Mahabharata, especially when discussing the continuation of royal lineages. The text presents several instances where this practice was employed. For example, the narrative of Yayati’s sons, Yadu and Puru, and their subsequent lineages is detailed. The story of Yayati’s curse on Yadu, and Puru’s lineage continuing, is a key element. The text also delves into the birth of mythological figures and the complex family ties that bind them.

The narrative of Yayati’s son, Yati, and his interaction with Devayani, the daughter of Shukracharya (a Brahmin), and Sharmishtha, a princess of the Asura (demon) clan, provides a detailed account of inter-varna and inter-clan relationships and their consequences. This intricate weaving of narratives illustrates the societal norms and practices prevalent during the period when these stories were conceptualized or compiled. The detailed accounts of births, curses, and divine interventions highlight the epic’s unique approach to explaining origins and perpetuating certain beliefs and social structures.

The Intertwined Destinies of Yati, Devayani, and Sharmishtha

The Mahabharata recounts the story of Yati, a descendant of Manu, who encounters Devayani, the daughter of the Brahmin sage Shukracharya. Devayani, the daughter of Shukracharya, the guru of the Asuras, falls into a well and is rescued by Yati. Devayani, impressed by Yati’s lineage, proposes marriage. However, Yati, a Kshatriya, hesitates due to the difference in their social standings (Brahmin and Kshatriya). Devayani, angered by his refusal, complains to her father Shukracharya. Meanwhile, Devayani’s friend, Sharmishtha, a princess of the Asura king Vrishaparva, gets into an argument with Devayani during a bath. Sharmishtha, in anger, pushes Devayani into the well.

Later, Devayani’s father, Shukracharya, intervenes, and a deal is struck where Sharmishtha becomes Devayani’s slave. This complex interplay of relationships, caste, and power dynamics sets the stage for further events in the epic, including the eventual marriage of Yayati to Devayani and the birth of their children, including Yadu and Puru. The narrative also highlights the social implications of such unions and the role of divine intervention or curses in shaping destinies. Source

The ‘Abhir’ and the Yadavas: A Question of Identity

The text raises questions about the identity of the Abhiras, who were historically associated with the Yadavas. According to Manu Smriti (Chapter 3, verse 15), children born from a Brahmin man and a Vaishya woman were called ‘Abhira’. Historically, the term ‘Abhira’ was used until the 19th century, and it was only with the advent of democracy and the need for vote banks that the term ‘Yadava’ was popularized and associated with the descendants of Yadu. The Mahabharata’s narrative suggests that Yadu, born from a Kshatriya father (Yayati) and a Brahmin mother (Devayani), was considered a Kshatriya.

This contrasts with the Manu Smriti’s classification of ‘Abhira’ as a mixed caste resulting from a Brahmin-Vaishya union. The Valmiki Ramayana (Yuddha Kanda, Chapter 22) also describes the Abhiras as a fierce and sinful people inhabiting the desert regions of Rajasthan. This discrepancy between the descriptions in the Mahabharata, Manu Smriti, and the Ramayana raises doubts about the direct lineage claims made by some groups today, suggesting a potential misinterpretation or deliberate conflation of different historical and mythological accounts.

The critical analysis points to a lack of direct connection between the Yadavas of the Mahabharata and the modern communities claiming descent from them, especially when considering the divergent descriptions and classifications.

The Caste of Krishna’s Ancestors: A Critical Examination

The Mahabharata’s genealogical accounts are often used to establish connections to figures like Krishna. However, the narrative regarding Krishna’s ancestry, tracing back to Yadu, presents a complex picture. Yadu’s mother was Devayani, a Brahmin, and his father was Yayati, a Kshatriya. This union, according to the Manu Smriti’s classification of ‘Abhira’ (resulting from a Brahmin father and Vaishya mother), does not directly align with the modern understanding of Yadavas or the caste system.

The text also notes that Kunti, Krishna’s aunt, was from the Yaduvansh. The narrative further delves into the birth of Pandu and Dhritarashtra, sons of Vichitravirya, and how their lineage continued through ‘niyoga’. This intricate web of relationships and births, including the birth of Karna from Surya and Kunti, and the Pandavas through divine intervention and ‘niyoga’, highlights the epic’s engagement with complex procreation methods.

The Birth of the Pandavas: Divine Intervention and ‘Niyoga’

The Mahabharata vividly describes the birth of the Pandavas, employing divine intervention and the practice of ‘niyoga’. After Pandu, the king, was cursed by a sage that he would die if he had intercourse with his wife, he was unable to have children naturally.

Consequently, his wives, Kunti and Madri, resorted to ‘niyoga’. Kunti, blessed with a boon from the sage Durvasa, could invoke any deity and receive children. She first invoked Yama, the god of dharma, giving birth to Yudhishthira. She then invoked Vayu, the god of wind, resulting in the birth of Bhima. Her third invocation was to Indra, the king of gods, who blessed her with Arjuna. Madri, Pandu’s second wife, invoked the Ashvins, twin horsemen gods, and gave birth to Nakula and Sahadeva.

This narrative emphasizes the extraordinary circumstances surrounding the birth of the Pandavas, highlighting the role of divine boons and the acceptance of ‘niyoga’ as a means to continue lineage in the absence of natural procreation. How do these divine births influence our understanding of legitimate lineage?

The descriptions of the specific months and celestial alignments during their births (e.g., Bhima’s birth during Purnamai Trayodashi when the sun was at its zenith, and Arjuna’s during the month of Phalguna) suggest an attempt to imbue these births with astrological and cosmic significance, possibly indicating the period when these narratives were being codified and integrated into the broader Vedic framework.

The Genesis of Karna: A Tale of Divine Union and Social Ostracization

The birth of Karna, the half-brother of the Pandavas, is a poignant narrative within the Mahabharata. Kunti, while still unmarried, invoked the Sun God, Surya, through a mantra gifted by Sage Durvasa. Surya appeared before her, and despite Kunti’s initial reluctance due to her virginity, he had intercourse with her, resulting in the birth of Karna.

Karna was born with divine armor and earrings, signifying his celestial parentage. However, fearing social stigma and the consequences of an out-of-wedlock child, Kunti abandoned the infant Karna. Karna was later found and raised by a charioteer, Adhiratha, and his wife Radha.

This narrative of Karna’s birth and subsequent abandonment highlights themes of divine destiny, social judgment, and the tragic consequences of societal norms. The text also suggests that Surya, the Sun God, bestowed upon Kunti the power of retaining her virginity even after childbirth, a detail emphasized to explain how she could later have children with Pandu through divine invocation. This aspect of regaining virginity is a recurring motif in several mythological accounts, often used to legitimize subsequent unions and births within a lineage.

The Unnatural Births of the Kauravas

The birth of the Kauravas, the hundred sons of Dhritarashtra and Gandhari, is depicted through a series of extraordinary and unnatural events, further emphasizing the epic’s departure from conventional biological processes. Gandhari, pregnant for a prolonged period, eventually gave birth to a lump of flesh. Dhritarashtra, advised by the sage Vyasa, had this lump divided into a hundred and one pieces. These pieces were then placed in a hundred jars filled with ghee (clarified butter) and kept for two years. Upon opening the jars, a hundred sons and one daughter were born.

The text also mentions that while Gandhari was pregnant, Dhritarashtra had a child, Yuyutsu, from a Vaishya woman. The birth of Duryodhana is particularly described as a grotesque event, with the infant crying like a donkey. These narratives, especially the descriptions of births from flesh and the consumption of ghee, suggest a symbolic representation of creation and gestation rather than literal biological accounts.

The mention of specific months and celestial alignments during these births might also indicate the period when the epic was being compiled, aligning with the development of the Indian calendar system and astrological knowledge. The grotesque descriptions are often interpreted as symbolic representations of the Kauravas’ negative qualities and their destined downfall.

The Scientific Claims and the Reality of Ancient Knowledge

Proponents of the Mahabharata as a scientifically advanced text often point to descriptions of births and celestial events as evidence of ancient Indian scientific prowess. For instance, the division of Gandhari’s flesh lump and its placement in ghee-filled jars is cited as an example of early embryological understanding or perhaps even cryopreservation.

Similarly, detailed astrological configurations during the births of the Pandavas are presented as evidence of advanced astronomical knowledge. However, critics argue that these descriptions are highly symbolic and mythological, rather than literal scientific accounts. The technology available at the time would not have supported such complex biological or astronomical feats as described.

The use of ghee, a common preservative, and the symbolic representation of celestial bodies might have been used to lend an aura of mystique and divine validation to the narratives. The text’s reliance on divine intervention and curses further distances it from a purely scientific explanation, suggesting that the authors were more concerned with conveying moral and philosophical messages than with documenting empirical scientific facts. The argument that ancient Indians possessed advanced technology, such as nuclear weapons or aircraft, based on interpretations of these epic descriptions, is generally considered speculative and lacking in concrete evidence.

The Brahmanical ‘Spin’ on Ancient Narratives

The compilation and dissemination of the Mahabharata occurred during a period when Brahmins held significant cultural and religious authority. As Buddhism declined in India, Brahmins played a crucial role in preserving and transmitting ancient Indian traditions. It is argued that during this process, they may have subtly infused their own ideology and social agenda into the existing narratives. The repeated emphasis on the importance of Brahmins, the glorification of Vedic rituals, and the justification of the caste system through mythological stories could be seen as evidence of this Brahmanical influence.

The scriptures often portrays Brahmins as recipients of donations, beneficiaries of rituals, and as figures deserving of utmost respect and reverence. This recurring theme, appearing every few verses, suggests a deliberate effort to reinforce the social and economic standing of the Brahmin class in a post-Buddhist era, where they needed to secure patronage from the ruling elites.

The comparison to Bollywood films, where songs are interspersed to enhance entertainment value, is used to illustrate how the ‘Brahminical agenda’ might have been integrated into the narrative to ensure its continued relevance and acceptance.

Conclusion: Re-evaluating the Mahabharata for Historical Truth

The Mahabharata, while a profound repository of philosophical, ethical, and cultural insights, presents a complex historical landscape. The detailed accounts of procreation, divine interventions, and intricate genealogies, particularly those involving ‘niyoga’ and celestial births, challenge a literal interpretation as purely historical records.

The text’s apparent influence from Buddhist and Jain traditions, along with the pervasive Brahmanical emphasis on rituals and social hierarchy, suggests a dynamic process of compilation and adaptation over centuries. The critical examination of these elements encourages a re-evaluation of the Mahabharata not just as history, but as a socio-religious and literary construct that reflects the evolving beliefs, practices, and power dynamics of ancient India. Understanding these layers allows for a more nuanced appreciation of the epic’s enduring legacy.

What You Can Do?

To foster a deeper and more critical understanding of the Mahabharata, consider the following actions:

- Engage with Diverse Interpretations: Explore scholarly analyses and historical research that question the literal historical claims of the Mahabharata. Seek out perspectives that highlight the epic’s literary, philosophical, and social dimensions.

- Study the Text Critically: Read the Mahabharata with an analytical mindset, paying attention to the origins of characters, the social practices described (like ‘niyoga’), and the recurring themes. Compare different versions and commentaries to gain a broader understanding.

- Verify Historical Claims: Cross-reference any historical assertions made within the Mahabharata with established archaeological and historical evidence. Be wary of claims that lack corroboration from independent sources.

- Promote Rational Discourse: Engage in discussions that encourage critical thinking and rational inquiry about religious and historical texts. Challenge unsubstantiated claims and promote evidence-based understanding.

- Educate Yourself on Historical Context: Learn about the periods in which different parts of the Mahabharata are believed to have been compiled, considering the influence of contemporaneous religious and philosophical movements like Buddhism and Jainism.

Unmasking Caste Bias: Impact of Shrimad Bhagavat Purana on Society

Ancient Indian Medicine: Beyond Common Narratives

Do you disagree with this article? If you have strong evidence to back up your claims, we invite you to join our live debates every Sunday, Tuesday, and Thursday on YouTube. Let’s engage in a respectful, evidence-based discussion to uncover the truth. Watch the latest debate on this topic below and share your perspective!