The Necessity of Scrutinizing Historical Narratives

To truly grasp the fabric of Indian history, it is imperative to critically examine the major historical discrepancies and alleged scams that have been presented as fact. Often, narratives are perpetuated through established texts and referenced sources, leading to widespread acceptance without sufficient vetting. The danger lies in accepting presented ‘references’ at face value, without understanding the context of conspiracy or subsequent revision. A clear analogy can be drawn from the progression of scientific thought. Science constantly evolves through correction and update. Similarly, history, when presented selectively—omitting the updates or retractions of earlier findings—becomes a tool for perpetuating a specific, often biased, viewpoint. This practice is particularly evident in the landscape of conspiracy theories prevalent in India today.

Questioning the Foundations of History

Many purveyors of these theories cherry-pick statements from historical accounts that have since been updated or debunked, presenting them as immutable truths simply because they were once written down. They deliberately omit the crucial context that these findings were later superseded or shown to be part of a broader historical misrepresentation. How can we trust history if its foundations are constantly shifting beneath our feet?

- The Danger of Uncritical Reference Acceptance

- The Pattern of Scientific Revision vs. Historical Stagnation

- The Need for Systematic Historical Deconstruction

- Colonial Era Documentation and the Early Revelations

- The Manipulated Translations of Travelogues

- The Systematic Eradication of Buddhist Historical Evidence

- The Colonial Role in Rediscovering and Reinterpreting Scripts

- The Conspiracy of Script and Language Ownership

- The Fate of Artifacts and the Erasure of History

- Conclusion: What You Can Do?

The Danger of Uncritical Reference Acceptance

The reliance on aged textual evidence without historical cross-referencing is a major pitfall. When historical claims are backed by citations—‘Look, this was written in that book’—the typical reaction is immediate acceptance. However, this bypasses the necessary verification: Was the author credible? Was the context politically charged? Was the theory later discredited? A systematic approach to understanding history requires tracing the evolution of ideas. For instance, early scientific models, based on the limited experience available at the time, represented possibilities (‘May be this is how it works’).

Subsequent rigorous research either confirmed, modified, or completely replaced these models. Presenting only the initial, tentative model as the final truth constitutes a historical distortion. This selective presentation is the backbone of many contemporary Indian conspiracy theories. They thrive on presenting outdated or disproven frameworks as definitive proof, ensuring that the audience remains trapped in an older paradigm.

The Pattern of Scientific Revision vs. Historical Stagnation

The scientific community thrives on self-correction, moving towards increasingly complex understandings, exemplified by current discussions around the Higgs Boson and beyond. In contrast, certain historical narratives resist this natural process of updating. The refusal to acknowledge later corrections—the demerits or shortcomings identified by later scholars—locks the narrative into a specific, often less accurate, framework. This resistance is fundamentally anti-rational. By failing to present the full chronology of discovery and revision, one paints an incomplete, and potentially false, picture of the past.

The constant stream of unverified, speculative claims circulating in public discourse stems directly from this failure to apply the same critical scrutiny used in other fields to historical documentation. The core issue is not a lack of information but a deliberate refusal to accept information that contradicts the established, older, and often ideologically convenient, versions.

The Need for Systematic Historical Deconstruction

The remedy for this historical obfuscation is a systematic, chronological understanding of events and ideas. Many prevalent historical misconceptions are rooted in an over-reliance on what was understood or imagined during periods when foundational knowledge—such as understanding of ancient languages or societal structures—was rudimentary or heavily influenced by prevailing biases, often stemming from ancient texts mistakenly equated with Vedic or Puranic sources. To break free from this cycle, one must examine the writings produced during colonial periods, particularly the introductory sections or personal experiences recorded by scholars of that era.

These initial accounts often reveal the prevailing assumptions and the models constructed by those early researchers, providing a clearer baseline against which later, more accurate findings can be measured. By comparing these varied, sometimes contradictory, models presented by different thinkers of the time, one begins to realize that absolute certainty was elusive even then, making the rigid adherence to a single, often flawed, narrative today entirely illogical. If a narrative relies on ignoring volumes of contradictory evidence, is it history, or is it fiction cloaked in antiquity?

Colonial Era Documentation and the Early Revelations

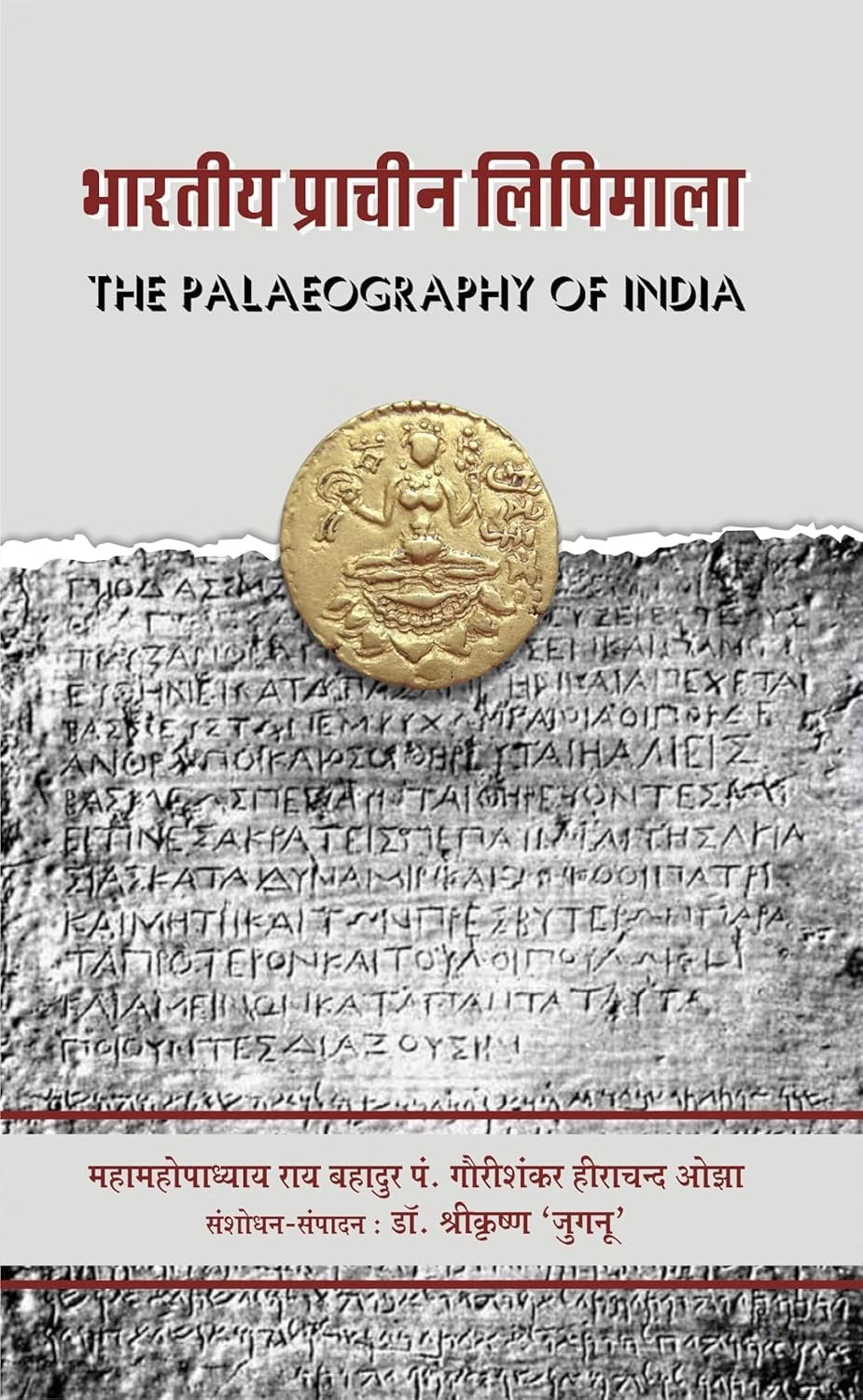

Examining texts from the British colonial period provides invaluable insight into the intellectual landscape of the time. The early scholars, particularly those working within the framework established by the colonial administration, documented prevailing beliefs and their own attempts to reconcile them with emerging archaeological and linguistic evidence. For instance, the work of Gaurishankar Hirachand Ojha, a well-educated individual who interacted closely with British archaeological research, offers a crucial window into this transitional phase.

Ojha, in his writings, recognized the need to align traditional understanding with verifiable modern research methods being employed by the British. His clear objective, as documented around 1918, was to convey these newer, research-based theories to the Brahmin community, whom he perceived as intellectually lagging and overly invested in mythological constructs that would not sustain in the modern world. He explicitly noted that the reliance on concepts like Satya Yuga, Treta Yuga, and Dwapara Yuga was jeopardizing their survival in a rapidly modernizing world.

G.H. Ojha’s Initiative and Its Context

Ojha’s decision to write in Hindi, rather than purely Sanskrit, was strategic—aimed at reaching those who could read the Devanagari script but were perhaps too immersed in what he considered fantastical literature to engage with empirical history. He observed the widespread belief in epics like the Ramayana and Mahabharata as literal historical accounts and sought to introduce scientifically grounded perspectives.

This recognition by a contemporary scholar that the prevalent narratives were essentially ‘fictitious’ or ‘speculative’ is a significant early indicator of the historical revisionism at play. He aimed to compile the scientific findings—what the English were discovering—and present them alongside, or in contrast to, the existing traditional accounts. This effort highlights that even within the traditionally educated circles, there was an awareness that the received history, deeply entwined with Puranic lore, was insufficient for understanding the evolving world order.

The Educational Divide and Historical Control

The socio-historical context of the early 20th century, as implied by Ojha’s observations, reveals a stark educational divide. Higher education remained largely inaccessible to large sections of the populace (Bahujans). Those from other castes who did pursue education often did so for limited vocational roles, such as clerical or military service under the British. This educational bottleneck ensured that new historical interpretations remained within a small, often privileged, stratum.

Ojha’s work thus becomes a key artifact showing an internal attempt to steer the historically privileged community toward accepting objective historical inquiry, motivated by a pragmatic concern for the community’s future relevance. His documented recognition of the community’s reliance on ‘imagination’ and ‘fantasy’ forms a counter-narrative to the later claims that Vedic knowledge was always empirically preserved and universally accepted.

The Suppression of Non-Vedic Sources

Ojha’s underlying acknowledgment points to a significant pattern: the history unearthed through archaeology and linguistics—much of it pointing toward Buddhist or pre-Vedic origins—was being consciously marginalized. The historical texts that did survive, or were later reinterpreted and published during the colonial era, were systematically filtered to eliminate non-Brahmanical influences.

The very basis of historical understanding was being contested. The fact that a scholar of Ojha’s standing felt compelled to document the contemporary state of affairs where mythology was mistaken for history underscores the extent to which the intellectual groundwork for the later, formalized historical establishment was being laid, often by sanitizing the records to fit a newly developing ‘Hindu’ historical framework, distinct from the burgeoning scientific consensus.

The Manipulated Translations of Travelogues

Another potent area where historical distortion occurred was in the translation of foreign travelogues. These accounts, often from Chinese Buddhist pilgrims, hold primary historical value as they document Indian society before the wholesale rewriting of history. However, when these translations were undertaken by individuals deeply embedded in traditional Brahmanical frameworks, the resulting texts became tools for reinforcing existing biases rather than revealing objective truth. A prominent case involves the translation of Fa-Hien’s travel accounts, where the translator, Jagmohan Verma, actively sought to project a Vedic primacy onto the text.

The Influence of Translator Bias in Fa-Hien’s Account

When readers encounter translations like Verma’s, which claim to be direct renderings of ancient Chinese accounts, they often encounter terms like “Brahman” or concepts that align with later Vedic narratives. This confusion arises because the translator, already operating under the assumption that Brahmanism predates or supersedes Buddhism, subtly injects this worldview into the translation. The original text, written in a context where Buddhism was ascendant, did not contain these anachronisms.

Consequently, readers are misled into believing that the ancient sources support the modern Brahmanical historical claims. The very act of translation becomes an act of historical revisionism when the translator’s ideology dictates the meaning of ambiguous or culturally specific terms.

The Case of Xuanzang’s Travelogue

A similar pattern is observed in the translation of Xuanzang’s (Hsuan Tsang’s) travel records, often rendered by individuals with surnames like Sharma or Thakur, who are identified as Brahmanical scholars. These translators similarly played the ‘game’ of inserting Vedic frameworks. When subscribers read these versions and question the presence of ‘Brahman’ terminology in a Buddhist context, their confusion is entirely understandable.

It is not a failure of comprehension on their part, but rather a direct consequence of reading a text deliberately shaped to downplay Buddhism’s historical dominance. This bias is precisely why, when the same travelogues are translated by scholars aligned with Buddhist or neutral perspectives, the prevalent Vedic/Brahmanical terminology disappears. The original accounts, free from the filter of Brahmanical interpretation, clearly depict a landscape dominated by Buddhist institutions, customs, and terminology.

Preservation Abroad vs. Destruction at Home

The stark difference between texts preserved abroad and those reinterpreted at home is telling. For instance, the Ramayana narratives found in Sri Lanka (translated in the 4th or 5th century) depict the central figure as a Bodhisattva. Similarly, versions from Japan (7th century) and Korea (5th century) feature Ram as a Bodhisattva. In contrast, the Indian version, particularly the one popularized by Tulsidas in the 16th-17th century, portrays Ram as a ‘Manuvadi Ram’ (a proponent of Manu’s laws).

The original texts, which traveled out of India before the full consolidation of Brahmanical dominance, remained protected from this revisionism. The texts that remained in India were subject to ‘Brahmanization’, the insertion of Vedic rituals, Yajnas (sacrifices), and Brahmanical dominance, creating the contemporary ‘Hindu’ scriptures. The true, original texts were either destroyed or carried away for safekeeping by migrating monks and scholars, subsequently recovered through international research.

The Systematic Eradication of Buddhist Historical Evidence

The process of ‘Brahmanization’ was not merely about rewriting texts; it involved the physical destruction and co-option of historical artifacts. Many key historical records from the time of the Buddha and subsequent dynasties, which clearly evidenced a Buddhist social order, were either repurposed or actively destroyed to erase their origins. The primary sources available pre-colonial era were not the Brahmanical texts that form the basis of much current religious literature, but artifacts left by the dominant socio-political order of the time: Buddhism.

The Value of Stupas, Inscriptions, and Coins

The author of the book The Palaeography of India published in 1918 explicitly states that the primary sources for understanding the history from the Buddha’s time onwards are the numerous stupas, temples (which were Buddha temples), caves, ponds, and wells built by royal and wealthy individuals. Furthermore, inscriptions found on pillars and the pedestals of statues, as well as land grant documents dedicated to monasteries, and the coinage of kings are considered the main sources of the ‘true history’ of that time.

This list overwhelmingly points to a Buddhist-centric historical record. The wealth and royal patronage clearly flowed towards the Shramana traditions, indicating that the ruling and affluent classes were overwhelmingly Buddhist. This contradicts modern claims of continuous Brahmanical dynasties and wealth prior to Muslim or British arrival.

The Lost Scripts and the Fabricated Lineages

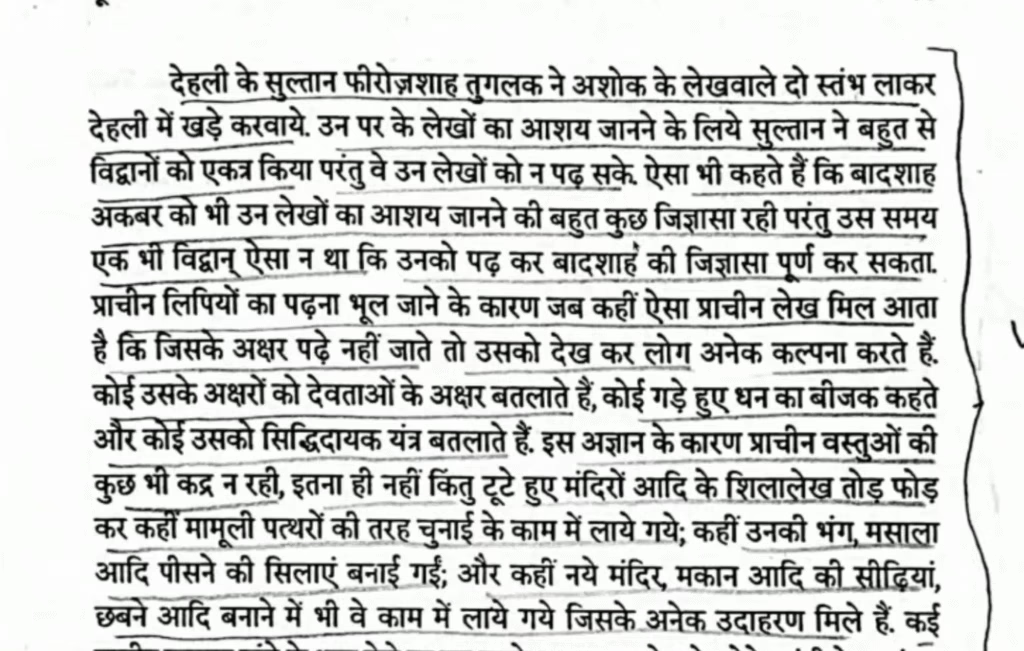

A crucial element of this historical obfuscation was the deliberate forgetting or denial of ancient scripts. The text notes that with the passage of time, people forgot how to read ancient scripts. A key instance cited is the failure of Brahmanical scholars to decipher the Ashokan pillars, even when commanded to do so by powerful rulers. When the Delhi Sultan Firoz Shah Tughlaq brought two pillars of Emperor Ashoka to Delhi, he gathered many scholars, but not a single Brahman could read the inscriptions.

Even Emperor Akbar, centuries later, could not find a single scholar among his court to interpret the script. This inability to read the foundational historical records—the script used by the Mauryan and post-Mauryan empires—is central to the conspiracy. If they could not read the actual records, their claims about prior history were based purely on oral tradition or later fabrication. When unable to read inscriptions, people resorted to baseless speculation, claiming the characters were divine writings or indicators of hidden treasure, rather than acknowledging their inability to read a script they had intentionally allowed to vanish.

The Fabrication of Royal Genealogies

The book further exposes how royal genealogies (Vanshavalis) that are often cited today were themselves inventions of a later period. Before the systematic historical reconstruction led by British scholars, knowledge of kings like Vikram, Bappa Rawal, Bhoj, and Prithviraj was vague, limited to mere names recited without accurate chronology.

It was only through painstaking research by colonial scholars, often in collaboration with the few locals who could assist, that these timelines began to solidify. Crucially, the text points out that the established genealogies, often found in Puranas or similar texts, were riddled with errors and fabricated names. The Bhats (Bards) and Charans (storytellers) created genealogies by inventing hundreds of arbitrary names before the 14th century, which were then carefully guarded as ‘true historical records.’ This fabrication served to create a fabricated continuum of Brahmanical rule stretching back into antiquity, masking the actual historical dominance of Buddhist or other non-Vedic rulers.

The Colonial Role in Rediscovering and Reinterpreting Scripts

The arrival of British scholars marked a turning point, ironically, because they applied empirical methods to texts and artifacts that had been deliberately obscured or forgotten by the indigenous elite who claimed custodianship over history. These scholars established institutions dedicated to linguistic and archaeological research, leading to the decipherment of key scripts that unlocked direct historical access.

Decipherment of Brahmi and Kharosthi

A consortium of scholars, including Charles Wilkins, Pandit Radhakanta Sharma, Colonel James Todd’s guru Yatigyanachandra, Dr. B.G. Babington, Walter Elliot, Dr. Mill, and W.H. Wathen, worked painstakingly to read the Brahmi script and its derived forms.

James Prinsep, alongside Alexander Cunningham, was instrumental in deciphering the Kharosthi script. This systematic effort revealed a vast corpus of historical documentation previously inaccessible. The investment in this research was formalized, with funding approved by the Board of Directors in 1847, shifting archaeological research from a matter of individual interest to state-sponsored endeavor.

This process led to the publication of critical materials, such as James Fleet’s monumental work in 1888 on the inscriptions and land grants of the Guptas and their contemporaries, bringing Mauryan and pre-Maurya history into verifiable focus.

The Brahmi Script: A Linguistic Misnomer

A significant point of historical contention concerns the name ‘Brahmi.’ The book clarifies that the name Brahmi is not derived from the Hindu deity Brahma, as is commonly asserted in later narratives designed to reclaim the script’s origin. Instead, evidence from Buddhist texts clarifies its actual source. The Jain text Panna-Varnasutra (a much later work) lists 18 scripts, with the first being Bambhi (derived from Prakrit/Pali).

More definitively, the Buddhist text Lalitavistara, dating to the 2nd century CE, lists 64 scripts, with the first being Brahmi and the second Kharosthi.

The promotion of Buddhism across China from the 1st to the 8th century CE involved numerous Buddhist monks translating Sanskrit and Prakrit texts. This widespread transmission, documented in Chinese encyclopedias, established the recognition of these scripts internationally, long before Brahmanical scholars could effectively claim their lineage.

Sanskrit as a Buddhist Language in Antiquity

The prevalent misconception that Sanskrit was exclusively a Brahmanical language is directly challenged by the evidence of its use in the early centuries CE. The text notes that Chinese scholars studied Sanskrit and Prakrit texts primarily to understand the tenets of Buddhism.

This demonstrates that, during the period when major historical documentation occurred, Sanskrit was the scholarly and religious language of the Buddhist tradition. The fact that Chinese scholars zealously sought out Sanskrit texts indicates that this language held the keys to the religious and philosophical canon of that era—a canon that was overwhelmingly Buddhist, as evidenced by the 657 volumes Xuanzang carried back to China, and the 1,500 volumes taken by the monk Punyopaya in 655 CE. The preservation of these vast libraries in East Asia confirms that the intellectual core of ancient India, as documented in that era, was Buddhist.

The Conspiracy of Script and Language Ownership

The control over language and script became a battleground for asserting historical dominance. When empirical evidence contradicted the desired narrative, new conspiracy theories were manufactured to reclaim ownership over foundational elements of Indian culture, such as the Devanagari script itself.

The Claim of Vedic Origin for Devanagari

The book details efforts by Brahmanical scholars to prove that the Brahmi script, and by extension Devanagari, originated from a hypothetical ‘Vedic Picture Script.’ R.M. Shastri, known for propagating the disputed Kautilya’s Arthashastra (published around 1905), proposed that pre-idol worship involved symbolic representations, triangles, circles, and yantras, which he termed ‘Devanagar’ (written in the middle of the city/land). He argued that these symbols later evolved into the letters of the script, thereby lending the name ‘Devanagari’ (from Devanagar).

The book critically notes that while this line of reasoning might appear logically structured, it remains mere conjecture until it can be proven that the supposed source texts for these symbols predate the Mauryan period or the Vedic era itself. This attempt represented a clear move to anchor the alphabet in a contested ‘Vedic’ past, especially as archaeological evidence firmly pointed towards Brahmi’s non-Vedic (i.e., Buddhist) origins.

Jagmohan Verma’s Alleged Vedic Development

Jagmohan Verma, involved in translating Fa-Hien’s travelogue, also engaged in similar fabrications. He attempted to assert that the Brahmi script developed from a supposed ‘Vedic Picture Script.’ He drew arbitrary pictures to hypothesize the evolution of characters, but critically, he failed to provide a single piece of written evidence from an ancient source to support his imagined sequence of development.

This inability to produce verifiable proof when confronted by the hard evidence found in Buddhist travelogues and inscriptions (which used Brahmi/Dhammalipi) exposes the speculative nature of the counter-claims. The desperation to link the ancient script to Vedic origins demonstrates the lengths to which the narrative required an unprovable foundation.

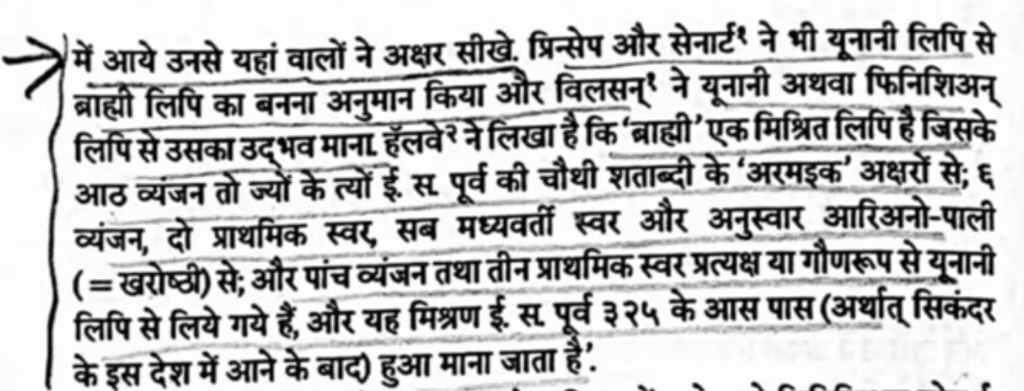

The Greek Hypothesis and Its Refutation

Another persistent conspiracy theory floated to explain the origin of these scripts was the ‘Greek Hypothesis,’ often attributed to scholars like Dr. Alfred Muller. This theory suggested that Indians learned their alphabets from the Greeks who arrived with Alexander the Great.

Scholars like Prinsep and Cunningham also explored links between Brahmi and Aramaic or Phoenician scripts, largely based on estimations of when the early inscriptions (like Ashoka’s) were created relative to Greek presence. Various scholars, including Wilson, Halvey, and Burnell, proposed derivations from Phoenician, Aramaic, or Egyptian hieroglyphic scripts, often based on superficial similarities or pure conjecture.

However, the text suggests that these hypotheses failed rigorous scrutiny, as direct linguistic matches between Brahmi/Kharosthi and these Western scripts could not be definitively established, reinforcing the growing consensus that the scripts were indigenous, rooted in the language environment of early Indian kingdoms—i.e., the Buddhist empire.

The Fate of Artifacts and the Erasure of History

The systematic destruction and misuse of historical artifacts underscore the depth of the commitment to erasing the genuine historical record, particularly the Buddhist past, which was evident through material culture.

Repurposing of Inscriptions and Seals

The most shocking revelation detailed in the 1918 text concerns the physical desecration of historical records. Since the contemporary elite could not read the ancient Brahmi inscriptions on pillars or stone tablets, they treated them as common materials.

Inscriptions from temples (which were Buddhist temples) were broken up and used as ordinary stone for construction—even for the walls of new structures. Worse, some inscribed stones were ground down to make mortar or used as grinding stones (silvattas) for spices and grains. This shows a profound ignorance and disrespect for the historical record, treating inscriptions of mighty emperors as mere raw material. This destruction occurred long before the British uncovered the true significance of these artifacts, pointing to an internal dismantling process coinciding with the decline of Buddhism.

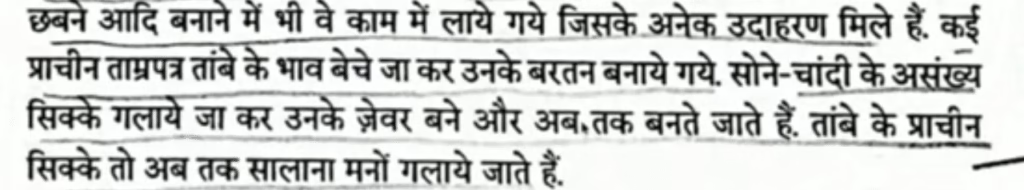

The Melting of Coins and Copper Plates

The economic materials of history were also systematically melted down. Numerous copper plates (tamrapatras) bearing royal edicts, which could have provided extensive dynastic details (like those from the Gupta period, often cited by modern proponents of a Hindu Golden Age), were sold as scrap copper based on weight alone.

The people doing this—those who had the right to own precious metals and the inclination to melt them—were clearly not the historically subjugated Shudras or Antyaj, who were barred from possessing wealth or using metal utensils. Similarly, countless gold and silver coins bearing inscriptions, which could have precisely dated rulers and documented political events, were melted down to make jewelry. The author notes in 1918 that this practice was ongoing, highlighting a deliberate cultural preference for ephemeral material wealth over enduring historical knowledge. The systematic destruction of these material proofs serves as a powerful testament to an organized effort to liquidate the primary historical evidence of the non-Vedic past.

The Historian’s Acknowledgement of Brahmanical Culpability

The author of the 1918 book implicitly admits that this state of affairs—where historical primary material was lost, destroyed, or rendered incomprehensible, was the direct result of the societal shift that marginalized non-Brahmanical knowledge systems. He observes that the vast historical record was hidden in deep darkness, only to be gradually revealed as archaeological evidence emerged, much of it unearthed by foreign explorers.

The text concludes that the loss of knowledge was so profound that until the systematic cataloging efforts began (like those culminating around 1893, leading to the publication of ancient script manuals), no single book existed in India from which one could reliably ascertain ancient history. The irony is stark: the very community claiming guardianship over ancient wisdom was simultaneously the agent of its physical annihilation.

If you want to buy the book:-

एशिआटिक सोसाइटी बंगाल के द्वारा कार्य आरंभ होते ही कई विद्धान अपनी रूचि के अनुसार भिन्न-भिन्न विषयों के शोध में लगे कितने एक विद्धानों ने यहां के ऐतिहासिक शोध में लग कर प्राचीन शिलालेख, दानपत्र और सिक्कों का टओलना शुरू किया, इस प्रकार भारतवर्ष की प्राचीन लिपियों पर विद्धानों की दृष्टि पड़ी, भारत वर्ष जैसे विशाल देश में लेखन शैली के प्रवाह ने लेखकों की भिन्न रूचि के अनुसार भिन्न-भिन्न मार्ग ग्रहण किये थे जिससे प्राचीन ब्राह्यी लिपि से गुप्त, कुटिल, नागरी, शारदा, बंगला, पश्चिमी, मध्यप्रदेशी, तेलुगु-कनड़ी, ग्रंथ, कलिंग तमिल आदि अनेक लिपियां निकली और समय-समय पर उनके कई रूपांतर होते गये जिससे सारे देश की प्राचीन लिपियों का पड़ना कठिन हो गया था; परंतु चाल्र्स विल्किन्स, पंडित राधाकांत शर्मा, कर्नल जेम्स टाड के गुरू यति ज्ञान चन्द्र, डाक्टर बी.जी. बॅबिंगटन, बाल्टर इलिअट, डा. मिल, डबल्यू, एच. वाथन, जेम्स प्रिन्सेप आदि विद्धानों ने ब्राह्यी और उससे निकली हुई उपयुक्त लिपियों को बड़े परिश्रम से पढ़ कर उनकी वर्ण मालाओं का ज्ञान प्राप्त किया, इसी तरह जेम्स प्रिन्सेप, मि. नारिस तथा जनरल कनिंग्हाम आदि विद्धानों के श्रम से विदेशी खरोष्टी लिपि की वर्णमाला भी मालूम हो गई. इन सब विद्धानों का यत्न प्रशंसनीय है परंतु जेम्स प्रिंन्सेप का अगाध श्रम, जिससे अशोक के समय की ब्राह्यी लिपि का तथा खरोष्ठी लिपि के कई अक्षरों का ज्ञान प्राप्त हुआ, विशेष प्रशंसा के योग्य है।

Conclusion: What You Can Do?

The historical analysis presented reveals that the current understanding of Indian history is built upon selective evidence, often ignoring the systematic erasure of contrary evidence, particularly that related to the long dominance of Buddhism. To navigate this landscape of intentional confusion, proactive engagement is required:

- Demand Contextual Transparency: Always question historical citations. Do not accept a reference solely because it exists; investigate if the theory has been updated, revised, or discredited by later scholarship. Understand that a text written in 1918 is itself a historical artifact reflecting specific contemporary biases and research limitations.

- Prioritize Material Evidence: Focus on archaeological findings, deciphered inscriptions, and international textual preservation (e.g., Chinese and Tibetan records) over purely internal, continuously revised Puranic or traditional narratives. Material evidence predating the rewriting phase is the most reliable baseline.

- Recognize Linguistic Reclamation Efforts: Be critically aware of attempts to rename linguistic features (like ‘Brahmi’ becoming ‘Brahma-related’) to assert cultural ownership over concepts that originated in non-Vedic traditions. Verify the etymology of terms against documented primary sources like the Lalitavistara.

- Study the Chronology of Discovery: Understand that much of what is considered ‘established Indian history’ regarding Mauryan and earlier periods was only reconstructed after the decipherment of scripts (post-1830s) and the discovery of major sites. Before this, the narrative was largely based on guesswork and ideological pre-disposition.

- Educate Others on Historical Manipulation: Actively challenge the tendency to accept genealogies created by later bards or biased translations of primary sources (like Xuanzang) as definitive history. Highlight the systematic destruction of primary materials like copper plates and coins.

Read more about Valmiki Ramayana: Shambuka Episode Exposed Casteism

Find out more about Adivasi History & Struggle for Justice in India

Disclaimer:

- Brahmanization: The process of editing, reinterpreting, or injecting Vedic/Brahmanical concepts, rituals (Yajna, Havan) and social hierarchies into pre-existing historical, religious, or cultural records, primarily to establish Brahmanical primacy.

- Conspiracy Theory (in this context): The deliberate omission or distortion of historical facts, often supported by selective referencing of outdated or misinterpreted texts, to maintain an ideologically favorable historical narrative against empirical evidence.

- Brahmi/Dhammalipi: The script used extensively during the Mauryan and post-Mauryan periods. The analysis suggests its origin lies within the Buddhist (Dhamma) tradition, contrary to later Brahmanical claims of derivation from Brahma.

- Tamrapatra (Copper Plate): Ancient land grant documents or official records inscribed on copper. Their destruction highlights the systematic erasure of administrative and historical records predating Brahmanical literary dominance.

Do you disagree with this article? If you have strong evidence to back up your claims, we invite you to join our live debates every Sunday, Tuesday, and Thursday on YouTube. Let’s engage in a respectful, evidence-based discussion to uncover the truth. Watch the latest debate on this topic below and share your perspective!