The Pervasiveness of Casteism

Many describe casteism as the backbone of the Hindu religion and society in India. Its influence deeply embeds itself, shaping religious, social, and economic processes across the nation. While society discusses various forms of casteism, a particularly insidious and subtle manifestation exists in the very names of places where people live, study, and work. This article delves into the controversy surrounding caste-based names assigned to villages, towns, and schools in India. It explores how these names perpetuate discrimination and humiliation, even decades after India’s independence. It contrasts the government’s proactive approach to changing names associated with Muslim history with its apparent inertia regarding caste-based place names, highlighting a critical aspect of ongoing social inequality.

Table of Contents:

- Government Focus on Changing Muslim Place Names

- The Emergence of the "Jati suchak Naam" Issue

- The Nature of Caste-Based Place Names

- Experiences from the Ground: A Case Study

- Perspectives from Chamari Village

- Perspectives from Chamroha Village

- Wider Prevalence and Systemic Issues

- Government Inaction and Societal Indifference

- The Pain of Caste-Based Names

- Conclusion

- What can you do?

- Disclaimer:

Government Focus on Changing Muslim Place Names

A Post-2014 Trend

Since 2014, with the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) affiliated government coming into power, a notable emphasis has emerged on altering the names of places, particularly those in Muslim-majority areas or bearing Muslim-sounding names. Supporters often frame this drive as an effort to correct historical mistakes, erase the markers of past invaders or Muslim culture, and re-establish symbols of Hindu culture and perceived historical glory.

Examples Across States

This phenomenon is observed across several states with BJP governments. In Uttarakhand, reports indicate authorities have changed multiple Muslim-sounding names for towns and areas. Examples include Aurangzebpur, renamed Shivaji Nagar; Gaziwali, changed to Harinagar; Chandpur, altered to Jyotiba Phule Nagar; and Mohammadpura Jat, renamed Mohananpur Jat. In Dehradun, Miawala was changed to Ramjiwala and Pirwala to Kesari Nagar. Even prominent roads like Nawabi Road became Atal Marg. Reports indicate a list of 31-33 such name changes focused specifically on names associated with the Muslim community.

Uttar Pradesh, under its current leadership, has also been prominent in this activity. Major cities saw their names altered, such as Allahabad, renamed Prayagraj, and Faizabad, which became Ayodhya. The Mughalsarai railway station changed to Pandit Deen Dayal Upadhyay Nagar. Even nationally significant sites like the Mughal Garden at Rashtrapati Bhavan were renamed Amrit Udyan in 2023.

Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh Following the Same Formula

Maharashtra, also governed by the BJP, followed suit. The names of Aurangabad and Osmanabad changed to Sambhaji Nagar and Dhara Shiv Nagar, respectively. Further demands and considerations for name changes persist, with calls to rename Khuldabad to Ratnapur and Daulatabad to Devgiri.

Madhya Pradesh actively participated in this trend. Habibganj Railway Station was renamed Rani Kamalapati Railway Station. A proposal was made to rename Jabalpur’s Dumna Airport after Durgavati, and Minto Hall was converted to Kushabhau Thakre Convention Hall. The state’s Chief Minister, identified as belonging to the OBC community, has also involved himself in this effort. Hindu organizations reportedly considered a list of 54 Islamic-sounding place names for change. A public statement by the Chief Minister questioned why places with Muslim names, especially if they lack a significant Muslim population, should not be renamed to reflect Hindu deities or culture. Specific village name changes cited include Mohammadpura Chhanai to Mohanpura, Dhabla Hussainpura to Dhablaram, and Khajuri Alladad to Khajuriram.

The stated objective behind these widespread changes consistently presents itself as correcting historical inaccuracies, removing the identity markers of foreign invaders, and solidifying Hindu identity and perceived historical glory. This process, underway since 2014, appears as a concerted effort by a specific ideological machinery.

The Emergence of the “Jati suchak Naam” Issue

Amidst the widespread campaign to change Muslim-sounding place names, a critical question began to emerge. Opposition parties in Madhya Pradesh particularly raised this question. If the government invests heavily in altering place names based on historical or religious associations, why the notable lack of action regarding place names that are explicitly caste-based? These names, often referring to specific Dalit or backwards castes, are seen as direct remnants of the discriminatory caste system and are argued to be a source of continuous humiliation for residents.

This question led to a demand for the government to address the numerous villages, hamlets, and schools whose names explicitly denote caste identities. The opposition argued that the ruling party exhibited a double standard. It was eager to promote Hindu names but unwilling to address names that perpetuate social divisions and caste discrimination, which is fundamentally unconstitutional. They suggested that deliberately preserving these names might be another method to keep the caste system alive and constantly remind individuals from lower castes of their perceived status.

Although caste-based place names exist across most states in North India, the demand for their change gained specific traction in Madhya Pradesh. This push questioned the government’s priorities and commitment to eradicating caste-based discrimination while actively pursuing name changes based on other criteria.

The Nature of Caste-Based Place Names

Defining “Jati suchak Naam”

“Jati suchak Naam” refers to place names that explicitly indicate a specific caste, often one traditionally considered ‘lower’ within the Hindu social hierarchy. Examples cited include Chamar Tola, Chamrauta, Dhimerola, Dhimaryan, Loharpura, Bhilayat, Kolar, Kolsara, Telipura, and Azipura. These names are not merely historical markers but are argued to be actively harmful in the present day.

Historical Roots and Social Impact

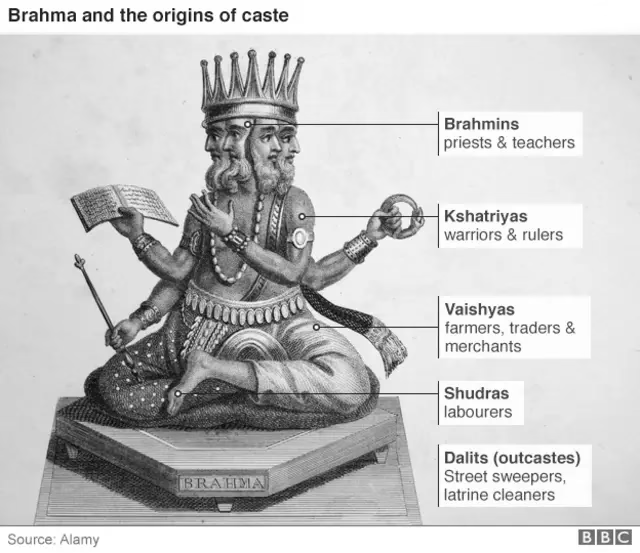

These names often trace their origins to a historical period. During this time, the Varn Vyavastha (caste system) was rigidly enforced. Authorities compelled individuals from ‘lower’ castes, often categorized as Shudras or Ati-Shudras (outcasts), to live on the outskirts of villages or cities. The areas where they resided were then named after their caste. The continued existence of these names serves as a perpetual reminder of this historical segregation and discrimination. People see them as directly linked to a discriminatory mindset. They contribute to the marginalization and insensitivity faced by vulnerable sections of society.

Schools and Public Places

Compounding the issue, some schools also reportedly use these caste-based terms in their names. Imagine attending a school named “Chamal Tola School” or “Dhimra School”. These names not only permanently label the identity of the place but also reinforce caste-based discrimination and inequality within the educational environment. For children attending such schools, their very address becomes a marker of their caste, potentially exposing them to mockery and prejudice from a young age.

The argument asserts these names are not simply inconvenient; they are constitutionally problematic because they perpetuate social discrimination and inequality. They maintain identities that the constitution sought to dismantle. While the constitution aimed to abolish untouchability and caste-based discrimination, the continued existence of these names in public spaces is seen as actively keeping that discriminatory system alive, both directly and indirectly. They preserve identities desired by those with a ‘Savarna’ (upper-caste) mentality.

Experiences from the Ground: A Case Study

The Dainik Bhaskar Study

To understand the real-world impact of these caste-based names, a case study was reportedly conducted by Neeraj Pandey, published in Dainik Bhaskar. The study focused on two villages in Madhya Pradesh: Chamari village in Sagar district and Chamroha village in Shivpuri district. It aimed to gauge the feelings and experiences of the residents regarding their village names.

The Two Villages Studied

Chamari village in Sagar district reportedly had a population of around 2500. It was predominantly OBC (around 1300) and SC (around 1200, mostly Ahirwar caste). It also had small populations of Brahmin and Thakur communities. Chamroha village in Shivpuri district reportedly had a population of around 5000, with SC residents (Jatav community) and OBC residents (Lodhi, Kewat, Pal communities).

Study Limitations Noted

The report on the study drew a critique regarding its apparent neutrality. The suggestion was that the study attempted to present a balanced view, potentially downplaying the extent of suffering faced by those most affected by casteism. Critically, observers noted that the study seemed to interview more residents from OBC communities in Chamari village and did not include substantial perspectives from the Jatav community in Chamroha, who are directly linked to the caste name.

The focus, according to the critique, seemed to be more on how OBC residents felt embarrassed rather than the core pain experienced by SC residents whose caste is explicitly named. The study included only one interview with an SC resident in Chamari village, whose primary concern was unrelated to the caste identity itself.

Perspectives from Chamari Village

OBC Residents’ Embarrassment

In Chamari village, residents from the OBC community expressed significant discomfort and embarrassment about the village name. Jagpal Yadav, a village head, reportedly stated that having a caste-based village name caused him shame. He felt that changing the name would bring relief. Other residents echoed this sentiment. Kishori Lal Lodhi, a 66-year-old resident, did not know how the village got its name but felt it might be over 200 years old, consistent with the historical pattern of lower-caste settlements outside main villages.

Social & Marital Impact

Residents like Chali Raja Lodhi described facing mockery from people in other villages or relatives when they mentioned their village name. He felt ashamed of the name during his college days. Crucially, he noted that as a person from the Lodhi caste (OBC), people often mistook him for belonging to a Scheduled Caste (SC) simply because of the village name. This forced him to constantly clarify his identity. Arvind Yadav also supported the demand for a name change, citing similar issues.

A particularly poignant example highlighted the difficulty faced by young people in the village regarding marriage. According to the report, a village resident stated that out of 1000 marriageable young men in the village, only 15 girls had been married into the village. Potential in-laws reportedly rejected alliances upon hearing the village name. This demonstrates a direct social consequence of the discriminatory naming.

The SC Resident’s View: Practical Concerns

In contrast to the embarrassment expressed by OBC residents, the perspective from Rakesh Ahirwar, a resident from the SC community, offered a different view. The Ahirwar caste is predominantly SC and forms a large part of the village’s SC population. He stated that he felt no problem with the name and even expressed pride in it. This perspective presents an illustration of how deeply normalized casteism can become. Those most affected may not even perceive the name as inherently problematic, or their immediate concerns overshadow issues of identity.

Rakesh Ahirwar’s primary concern regarding a name change was highly practical: the potential need to update all personal documents. He worried about the cost and effort involved in changing names on identity cards, property papers, and other records, and he stated this hassle would be a significant burden and preferred the name to remain unchanged for this reason. The issue was also linked to a broader lack of basic amenities like housing or gas connections.

He implied that for him, these pressing needs were more important than a name change. He felt that even if the village name changed, their caste identity (Ahirwar) would remain, and people would continue to address them by their caste. This reflects the deep-seated nature of caste identity in the region, particularly in Bundelkhand where caste affiliations are very strong.

Contrast between the perspectives of an SC vs an OBC

This stark contrast in perspectives within the same village highlights the complex reality of casteism. An OBC group feels embarrassed by a name associated with a different, lower caste, while an SC group belonging to the named caste is more concerned with the practical difficulties of change than the symbolic discrimination, or perhaps has internalized the identity to the point where the name itself is not the primary source of pain compared to other life struggles.

Perspectives from Chamroha Village

The second village studied was Chamroha in Shivpuri district. Unlike Chamari, the report here, seemed to focus less on the direct experiences of the dominant SC community (Jatav) whose caste name forms the village name.

The Bansal Family’s Stance

An interview was conducted with Rajendra Bansal, a resident of Chamroha. Notably, Mr. Bansal expressed opposition to changing the village name. His reasoning tied itself to ancestry. He stated that his ancestors were Zamindars (landlords) who had named the village. He firmly believed the name should not be changed under any circumstances. This perspective potentially reflects a desire from historically dominant groups to maintain the status quo and the markers of the old social hierarchy, where they held power over the communities living in areas named after their caste.

Critique of the Study’s Focus

The transcript critically observes that the Dainik Bhaskar study in Chamroha largely missed the voices of the Jatav community, who are directly affected by the caste-based name. Focusing on Mr. Bansal’s perspective, representing a dominant-caste historical viewpoint (Zamindar ancestry implied), highlights the challenge in capturing the lived experiences of those subjected to caste discrimination. It suggests that studies attempting to understand the impact of caste-based names must prioritize hearing from the individuals and communities whose castes are explicitly referenced in these names.

Wider Prevalence and Systemic Issues

Examples Across States

The two villages studied are not isolated examples. The report lists numerous other instances of caste-based place names across Madhya Pradesh and implies their presence throughout North Indian states. Examples include Goriya in Guna, Chamarbegda in Alirajpur, Koliya in Rewa, Bhilada in Shivni, Kolgaon in Chhindwara and Balaghat, Chamarkha/Chamarwa in Betul, Telipura in Shivpur, Loharpura in Bhind, Dhimarkhedi in Katni, and Chamarkhedi in Rajgarh.

Constitutional Implications and Symbolism

People describe these names as standing like “broken buildings of casteism.” They serve as constant reminders that while caste discrimination may have weakened in some aspects, it persists in subtle forms. People consider them unconstitutional because they perpetuate discrimination based on caste. They are seen as living symbols of the historical “outcaste” system and continue to place residents under the shadow of the caste mark. We can assert that these names are not just geographical labels. They embody and promote a discriminatory mindset, reinforcing the idea of a hierarchical society where certain identities are deemed inferior.

Government Inaction and Societal Indifference

Stated Government Position vs. Action

Despite the demands raised, including the issue reaching the state assembly and the President, the government’s response to changing caste-based place names appears hesitant. While Madhya Pradesh reportedly changed 65 village names, these changes primarily focused on names associated with Muslim identity, not caste. A state minister for Water Resources reportedly stated that the government would consider name changes if it received a demand.

Contrast with Muslim Names

This stance sharply contrasts with the proactive and extensive efforts made to change Muslim-sounding names. The reader should note that the government lacks the political will or interest in changing caste-based names, unlike its clear drive to change names associated with Muslim history. It suggests that certain sections of society, particularly upper castes, might derive a form of “sadistical pleasure” or “perverted pleasure” from seeing lower castes continue to be identified with these discriminatory names. This reinforces their own perceived higher status based on the notion of past karma within the caste system.

Societal Complacency

Beyond government inaction, the persistence of these names also points to a broader societal issue – a lack of empathy or understanding from those who are not victims of casteism. For someone living in a city with a dignified name, the pain and embarrassment experienced by someone from a village with a name like Chamroha or Dhimra might never occur to them.

This lack of awareness can be described as another facet of casteism itself – its visibility and impact are often only fully understood by those who suffer from it. We should note that if we lack the perspective to see it, casteism might appear non-existent in India, but with the right perspective, it becomes visible in every aspect of Hindu society. Imagine carrying a surname that constantly reminded you of your great-grandparent’s servitude. Is it so different from a village named after a caste historically deemed ‘untouchable’?

The Pain of Caste-Based Names

Living with a caste-based place name is described as a source of significant distress. Just as having a low caste identity is painful, and even more so when society uses those identities as insults or slurs, having a village, town, or school named after such an identity is deeply hurtful. Residents from these places might feel a constant burden of shame every time they must state their address.

The impact is particularly severe on children. Attending school or college and having peers discover their village name can make them a target of ridicule and jokes. This constant exposure to stigma from a young age can have lifelong psychological effects. The persistence of these names is seen as a failure of society to truly move beyond caste discrimination. It reflects a system that appears unwilling to erase the markers of historical oppression.

Therefore, changing these names is not merely a symbolic gesture. It is seen as a necessary step towards dismantling caste-based discrimination. It is a call to remove the explicit markers of historical segregation and humiliation that continue to affect the lives and dignity of individuals and communities.

Conclusion

The contrast between the enthusiastic renaming of places with Muslim associations and the reluctance to change caste-based names starkly illustrates the complex and often subtle ways casteism continues to operate in India. Caste-based place names are not harmless historical relics; they actively participate in perpetuating discrimination. They cause embarrassment, limit opportunities, and constantly remind specific communities of their marginalized status.

While governments prioritize renaming based on religious or historical narratives, the fundamental issue of caste-based humiliation embedded in geographical names remains largely unaddressed. If we can mobilize significant political will and resources to change names associated with one historical period, why the apparent inertia when it comes to symbols of centuries of internal, systemic oppression? Are we truly committed to equality for all, or only selective historical correction based on current political priorities?

What can you do?

President of India should take cognizance of this issue and initiate a process for changing such names. While this may seem a small task, it is argued to be crucial for upholding the dignity of citizens and the constitutional promise of equality. Beyond presidential intervention, a clear need exists for a nationwide campaign and process. This campaign should identify and rename all villages, towns, hamlets, and schools bearing caste-based names.

This effort should not confine itself to a single state but should be a concerted national movement to eliminate these explicit symbols of caste discrimination and contribute to a truly egalitarian society. Support campaigns advocating for this change, raise the matter with your elected representatives, and petition relevant authorities to take decisive action.

Disclaimer:

This article discusses terms used in the context of the Indian caste system as presented in the source material. The following terms are used based on their description and usage in the transcript:

- Casteism (Jativad): A system of social hierarchy and discrimination based on birth.

- Jati Suchak Naam: Names of places (villages, towns, schools) that explicitly refer to a specific caste name.

- SC (Scheduled Castes) / Dalit: Communities historically considered ‘lower’ caste and subjected to untouchability and severe discrimination.

- OBC (Other Backward Classes): Socially and educationally backward classes, also part of the caste hierarchy.

- Varn Vyavastha: The ancient Hindu social stratification system dividing society into four main classes (Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaishya, Shudra) and often including ‘outcastes’.

- Outcastes / Ati-Shudras: Communities historically placed outside the four-fold Varn system, often segregated and associated with impure occupations.

Read more about casteism in Prisons!!

Caste Discrimination: Unmasking Caste Reservation Hate

Do you disagree with this article? If you have strong evidence to back up your claims, we invite you to join our live debates every Sunday, Tuesday, and Thursday on YouTube. Let’s engage in a respectful, evidence-based discussion to uncover the truth. Watch the latest debate on this topic below and share your perspective!