Introduction: Unearthing Historical Caste Status

Historical records and religious texts often reveal surprising narratives about social structures and caste classifications. A significant historical debate revolves around the status of various groups, including powerful rulers and warriors, and their classification within the caste system. Were the groups who considered themselves Kshatriya and Vaishya historically recognized as such, or were they categorized differently in certain periods and texts? This article examines the history of Shudra classification and contested historical caste status.

This exploration, grounded in historical documents and legal proceedings from the British era, challenges popular understanding and brings to light evidence suggesting that many, including those in positions of power, were classified as Shudra according to certain Brahmanical interpretations.

Table of Contents:

- Historical Caste Status: Scriptural Views on Shudra Classification in Kaliyuga

- The Struggle for Historical Caste Status in British Indian Courts

- The Maratha Experience: Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj and the Coronation Dispute

- The Rajput Inheritance Case of 1857

- Brahmanical Theories: Annihilation and Adaptation

- Disclaimer: Understanding Key Terms

- Conclusion: Re-examining Historical Narratives on Caste Status

Historical Caste Status: Scriptural Views on Shudra Classification in Kaliyuga

According to certain Brahmanical texts, a theory emerged declaring the absence of true Kshatriyas and Vaishyas in the current age, known as Kaliyuga. This theory became a basis for classifying almost everyone outside the Brahmin class as Shudra. Two key scriptures are cited as foundational to this idea.

Vishnu Purana’s Prophecy on Future Kings

The Vishnu Purana is presented as a text that initiates the practice of classifying kings and warrior communities as Shudra. The British requested this text when setting up courts in India, seeking guidance on local laws and customs. The text reportedly contains prophecies about future kings and dynasties, specifically stating their classification in Kaliyuga.

King’s End of the Line

The 4th section, 21st chapter, verse 18 of the Vishnu Purana describes dynasties and predicts their end. It states that the dynasty “adorned with various king-sages, the cause of the origin of Brahmins and Kshatriyas,” will end with the birth of King Kshema in Kaliyuga.

After this point, all subsequent rulers are prophesied to be of Shudra stock. The 22nd chapter reportedly lists kings of the Ikshvaku dynasty, stating the lineage will continue until King Sumitra. Verse 13 reportedly states that after Sumitra’s birth, the lineage will end, and all subsequent rulers will be Shudras. The text also makes controversial claims about the lineage, suggesting King Sanjay’s son was Shakya, whose son was Shuddhodana, and his son was Rahul, potentially contradicting established historical timelines by placing the Ikshvaku lineage’s end long after Buddha’s time, suggesting it might have been composed or compiled during a later period.

The Vishnu Purana’s 24th chapter, focusing on the description of Kaliyuga kings and religions, provides a crucial passage. Verses 20-24 describe Mahanandi and his son Mahapadma Nanda, born from a Shudra woman. This Mahapadma Nanda is described as a second Parashurama, the destroyer of all Kshatriyas. The text then explicitly states that from that point onwards, kings would be of Shudra origin. This interpretation suggests that after Mahapadma Nanda, dynasties like the Maurya, Gupta, Pala, and Harsha, as well as all subsequent ruling periods, were considered Shudra by the composers of this text. This establishes a theological basis within certain Brahmanical scriptures for the belief that all rulers in Kaliyuga are Shudras.

Shrimad Bhagavatam Corroborates the Theory

The Shrimad Bhagavatam, also called Mahapurana, is another text cited as supporting the classification of subsequent rulers as Shudra. The 12th Skandha of this text echoes the narrative found in the Vishnu Purana.

It states that Mahanandi will have a son named Nanda from his Shudra wife. This Nanda is described as powerful and the lord of the Mahapadma निधि (treasure/wealth), hence called Mahapadma. Crucially, this text also states that he will be the cause of the destruction of Kshatriya kings. It concludes that from that time onwards, kings will mostly be Shudra and irreligious.

This reinforces the narrative that Mahapadma Nanda marked the end of Kshatriya rule, according to this text, and that subsequent dynasties, including the Mauryas, were considered Shudra. Brahmins invented this narrative and attributed it to ancient sages like Vyasa, establishing a belief among the public that all kings after a certain period were Shudras.

These scriptures, formed the basis of a Brahmanical theory prevalent during the British era, claiming that no true Kshatriyas or Vaishyas existed in Kaliyuga, effectively reducing all other groups to Shudra status in terms of ritual standing and classification in religious texts.

The Struggle for Historical Caste Status in British Indian Courts

During the British Raj, the caste system and its rules became subjects of legal disputes, particularly when traditional Brahmanical interpretations clashed with individuals’ aspirations or legal rights. Several court cases highlight the attempts by non-Brahmin groups to assert a higher status and the Brahmanical resistance to such claims, often citing the scriptural theories about Kaliyuga.

The Vaishya Case (1817-1845)

Let’s discuss a significant case originating in Andhra Pradesh in 1817. A wealthy Vaishya individual went to court, demanding that Brahmins perform Vedic rites for his ceremonies. He questioned why, despite his wealth and status, he was denied Vedic rituals which he believed were his right as a Dvija (twice-born).

The Vaishya community, or Komati class as referred to in the book, took the matter to court, filing a case against the assembly of Brahmins (Mantri Mahananda mentioned). The case lasted for 28 years, reaching the Privy Council in London in 1845. The core issue was whether the refusal by Brahmins to chant from the Vedas for Vaishyas constituted a denial of their civil rights. The Vaishyas sought legal recourse to force Brahmins to perform Vedic ceremonies for them, arguing they were Dvija.

Brahmins resisting Vaishyas

However, the Brahmins reportedly argued that Vaishyas were not entitled to Vedic rites according to their scriptures and that in Kaliyuga, true Vaishyas, like Kshatriyas, no longer existed. They contended that ceremonies for these groups should be performed according to the Puranas rather than the Vedas. The Puranas were described as containing deities and narratives influenced by Vajrayana Buddhism. The district court initially ruled in favor of the Vaishyas in 1833 but reversed the decision in 1838, supporting the Brahmins’ stance. The Vaishyas appealed to the Privy Council.

In 1845, after 28 years, the Privy Council rejected the Vaishyas’ appeal. The council ruled that the refusal of Vedic rites did not constitute a legally actionable injury. This decision, based on the prevailing legal interpretation of Hindu law at the time, essentially upheld the Brahmins’ right to deny Vedic rituals to the Vaishyas, implicitly supporting the idea that they were not entitled to them as per the Brahmanical view, thus failing to prove their status as Dvija in the eyes of the court and the dominant religious interpreters. This historical event demonstrates the legal challenges faced by groups attempting to assert a higher caste status and access to religious rituals traditionally reserved for Brahmins, Kshatriyas, and Vaishyas.

The reader should note the historical context: these groups often did not know their actual historical religious background, which was sometimes related to Buddhism and different from Brahmanism. Due to the loss of their own religious identity, they sought acceptance and validation from Brahmins, even when being rejected and classified as Shudra according to Brahmanical texts like the Puranas, which they were permitted to follow, unlike the Vedas.

The Maratha Experience: Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj and the Coronation Dispute

The struggle for recognition and status was not limited to merchant communities. Even powerful rulers faced challenges from the Brahmanical hierarchy. The case of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj presents a prime example that occurred even before the British court cases became prominent.

Initial Classification as Shudra

Born into the Bhonsle clan, Shivaji Maharaj established a vast empire. However, Marathi-speaking Brahmins in his vicinity reportedly classified him and his clan as belonging to the Shudra Varna . This classification became a significant obstacle when he sought a formal coronation (Abhiseka) to be recognised as Emperor (Chhatrapati).

Brahmins of the region refused to perform the necessary Vedic rites for his Abhiseka. Their refusal stemmed from the belief that in Kaliyuga, true Kshatriyas no longer existed, having been annihilated by Parashurama. Since Shivaji Maharaj was, in their view, a Shudra ruler, he was not eligible for a Vedic coronation traditionally performed for Kshatriya kings. Even his own Prime Minister, a Brahmin, reportedly denied his claim to being a Kshatriya. Imagine a powerful ruler being denied a key ceremony by his own advisors based on ancient textual interpretations – that’s the challenge Shivaji faced.

Seeking Validation and the Vratya Ceremony

Determined to gain legitimate status, Shivaji Maharaj sought a Brahmin who would perform the ceremony. He reportedly traced his ancestry to the Sishodiya dynasty of Mewar, aiming to connect himself to a recognised Kshatriya lineage like that of Maharana Pratap, who was respected for resisting the Mughals. However, this newfound genealogy failed to impress the local Brahmins in his court.

He then reportedly used his influence and wealth (referred to as offering “Halwa Puri” and money) to find a Brahmin who would validate his claim. This led him to Gāgā Bhaṭṭ from Banaras, who agreed to validate his Kshatriya status and perform the Abhiseka. Gāgā Bhaṭṭ reportedly developed a new theory to reconcile Shivaji’s claim with the Parashurama annihilation legend. He argued that while Parashurama did destroy most Kshatriyas, some pockets survived.

These surviving Kshatriyas, according to this new theory, were in a degraded state, reduced to a Shudra-like status due to the non-performance of the sacred thread ceremony (Upanayana) over generations. This provided a justification for Shivaji’s status and allowed for a ceremony called Vratya Stoma or Vratya Kesari.

The term Vratya is explained using Manusmriti, Chapter 10, verses 20 and 21. It describes Vratyas as Dvija men whose Upanayana संस्कार (sacrament) has not been performed, causing them to be fallen from the Savitri (Gayatri mantra). Verse 21 mentions that from Vratya Brahmins, degraded sons are born, who are called Avanta, Vatadhana, Pushpadha, and Shaikh. Gāgā Bhaṭṭ reportedly applied this Vratya concept to Shivaji Maharaj, effectively performing his Upanayana ceremony to elevate him to Kshatriya status.

Status Reduction After Shivaji

Despite the efforts to establish his Kshatriya status, the acceptance by Brahmins was short-lived. The book states that Gāgā Bhaṭṭ’s compromise “did not endure.” Within just three generations of Shivaji’s descendants, Brahmins reportedly reduced their status back to Shudra once again. The Brahmins, whom Shivaji had brought into his court, managed to reassert their traditional view. See image above.

The Peshwas, who later gained power, further cemented this shift. They reportedly portrayed Shivaji’s legacy as that of a “Go Brahmin Pratipalak” or “protector of cows and Brahmins”, shifting the focus from his status as a Kshatriya emperor to that of a ruler subservient to Brahmanical interests. To consolidate their political control, the Peshwas denied Shivaji’s descendants the privilege of Vedic rites, insisting on Puranic ceremonies instead, thereby reinforcing their classification as effectively outside the traditional Dvija fold eligible for Vedic rituals.

The Rajput Inheritance Case of 1857

Another significant legal battle highlighting the caste classifications in the British era occurred in 1857 in the Bengal Presidency. This case reached the Privy Council in London and directly challenged the Brahmanical theory of Kshatriya annihilation.

Inheritance Dispute and Caste Status

The case involved the inheritance of a deceased Rajput Raja. His son, Chautaria Run Murdun Singh, born from a marriage to a woman reportedly of an “inferior caste,” sought to claim his father’s inheritance. According to Hindu law at the time, especially as interpreted by Brahmins, inter-caste marriage, particularly with a woman of a lower Varna, could affect the legitimacy and inheritance rights of the offspring.

The opposing party, reportedly bringing forward a different child as the true heir, argued that Chautaria’s mother was of a lower caste, making him illegitimate according to the rules surrounding inter-caste marriages at the time. They invoked traditional caste rules to deny his claim.

Brahmin Testimony and the Shudra Classification

During this legal battle, a Brahmin पंडित (scholar/priest) was called to provide testimony regarding caste rules and the status of Rajputs. The Pandit’s reasoning was that a Rajput is of the Shudra caste. He further testified that according to Shastra (scriptural law), a son born to an individual of the Shudra caste, even from the womb of a slave (दासी – Dasi) or slave woman (स्लेव – Slave), is still considered his son and belongs to his caste.

This testimony is remarkable as it presents a Brahmin stating in a British court that Rajputs are fundamentally Shudra. The argument implied that since Rajputs were Shudra, their children, regardless of the mother’s specific lower status, would still be considered Shudra and thus legitimate heirs within that Shudra classification. The Pandit’s testimony aligned with the broader Brahmanical theory that true Kshatriyas had been annihilated by Parashurama, and therefore, all subsequent warrior classes like Rajputs were, in effect, Shudras in Kaliyuga.

Interestingly, the claimant himself, Chautaria Run Murdun Singh, also argued that the Kshatriya and Vaishya classes had ceased to exist and that only two classes remained in Kaliyuga: Brahmins and Shudras. He presented evidence from books by British authors researching Indian customs to support his claim that he too was a Shudra and therefore eligible for inheritance under the more flexible rules reportedly applied to Shudra inheritance at the time. He also presented evidence of his social acceptance, showing he ate and drank with his father and uncles to counter any suggestion that he was considered untouchable or of extremely low status.

Privy Council Decision of 1857

The Privy Council in London was tasked with resolving this conflict, navigating Hindu mythology and caste prejudices. Although Brahmins were not formal parties to this specific case, the Council’s decision in 1857 had significant implications for their theories. The Council rejected the argument based on the Parashurama legend.

The decision, while not explicitly defining what constituted a Kshatriya versus a Shudra legally, made it clear that despite the scriptural legends of Kshatriya annihilation, Brahmins could no longer claim to be the only surviving “regenerate” class (Dvija) in Kaliyuga based solely on that theory. This was considered a setback for the Brahmanical thesis that reduced all other Varnas to Shudra status in the current age. The case highlighted the discrepancy between traditional scriptural interpretations and the legal requirements of the British judicial system, demonstrating the challenges individuals faced seeking to navigate complex caste rules in matters of inheritance and status.

Brahmanical Theories: Annihilation and Adaptation

This reveals how Brahmanical theories regarding caste status, particularly that of Kshatriyas and Vaishyas, evolved and adapted over time. The core theory centered on the legendary actions of Parashurama.

The Parashurama Annihilation Legend

As cited from both the Vishnu Purana and Shrimad Bhagavatam, a key narrative is that Parashurama, an avatar of Vishnu, annihilated the Kshatriya class multiple times. The Mahabharata, Chapter 64, verses 4 and 5, is specifically mentioned as stating that Parashurama made the Earth “Kshatriya-sunya” (devoid of Kshatriyas) 21 times. This text reportedly portrays Kshatriya women seeking Brahmins for procreation after the annihilation, depicting the Kshatriya women in a negative light and explicitly stating that no Kshatriyas remained.

This scriptural narrative formed the basis for the Brahmanical claim that no true Kshatriyas existed in Kaliyuga. Brahmins used this theory to justify denying Vedic rites and asserting their supremacy as the sole surviving Dvija class.

The Vratya Theory as an Adaptation

However, when Brahmins faced powerful rulers like Shivaji Maharaj who sought Kshatriya status, a need arose to reconcile the annihilation theory with the reality of existing warrior communities. This led to the development of adapted theories, such as the Vratya concept Gāgā Bhaṭṭ used for Shivaji’s coronation.

This adapted theory, referenced in Manusmriti Chapter 10, posited that while many Kshatriyas were destroyed, some pockets survived. These survivors, however, had become degraded (Vratya) due to the non-performance of Upanayana over generations. This allowed for the possibility of elevating individuals from this ‘degraded’ status back to Kshatriya through specific ceremonies like the Vratya Stoma, as was done for Shivaji.

This demonstrates flexibility in Brahmanical interpretation, creating new theories (like some Kshatriyas surviving as Vratyas) where needed, particularly when dealing with powerful figures who could not be easily dismissed as mere Shudras, contrasting with the more absolute annihilation described in older texts like the Mahabharata. Was this adaptation a genuine re-interpretation or a strategic move? The historical context suggests it could be both.

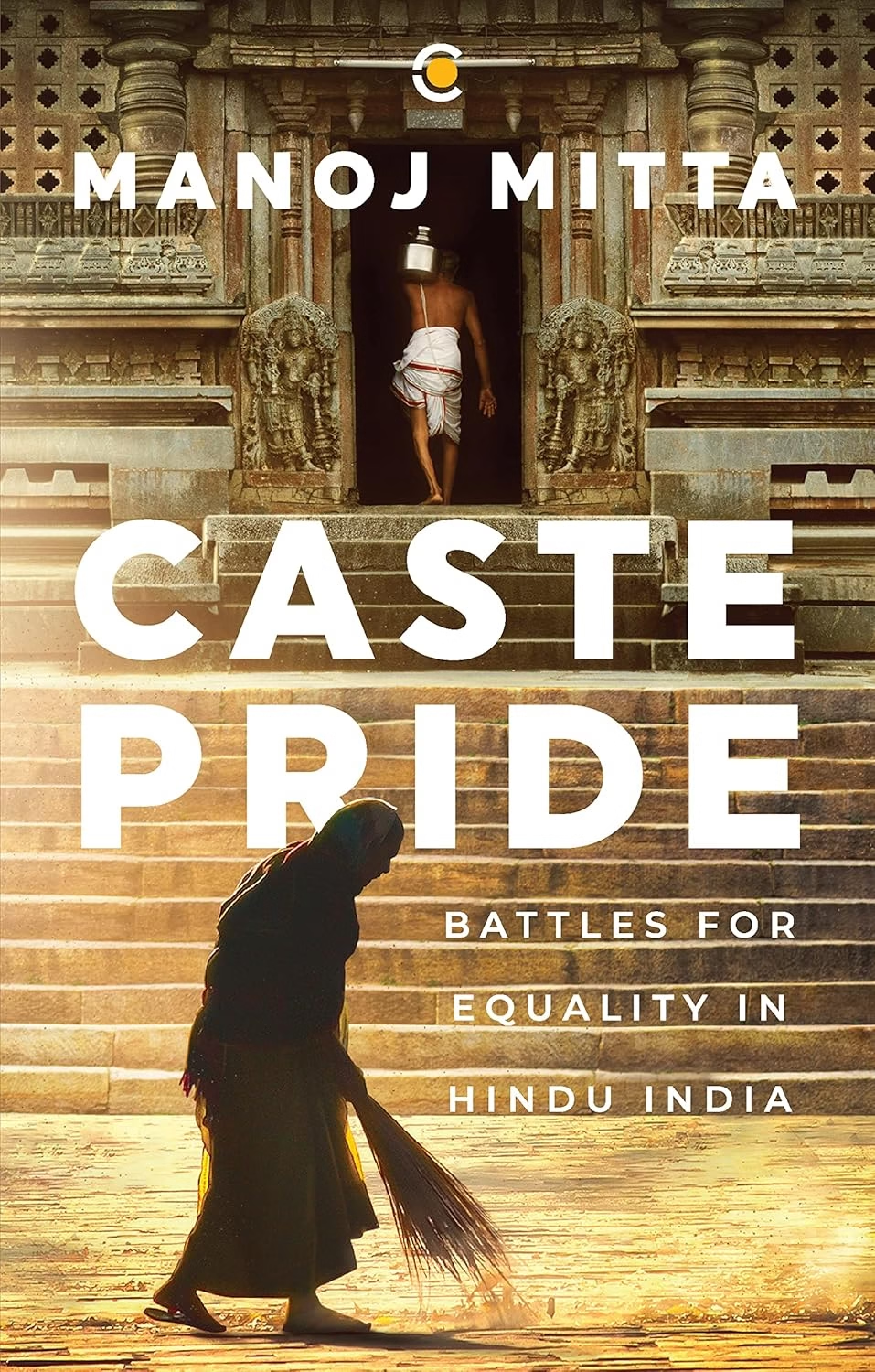

You can buy and read the book from here!!

In this masterful work, Manoj Mitta examines the endurance and violence of the Hindu caste system through the lens of the law. Linking two centuries of legal reform with social movements, he unearths the characters, speeches, confusions and decisions that have shaped the war on caste, mitigating how this ancient institution discriminated between Hindus across the board. Where they could live, how they could dress, whether they could go to a shop, a stream, walk a street or mingle, enter a temple, whom and how they could marry, which scriptures applied to whom, whether their actions, innocent or criminal, would attract punishment or impunity

Disclaimer: Understanding Key Terms

To ensure clarity, this article uses the following terms based on their context within the provided article:

- Shudra: Refers to a Varna or caste category, often considered the lowest of the four principal varnas in traditional Hindu texts. In the context of this article, it also refers to the classification applied to numerous groups, including historical kings and warriors, particularly in Kaliyuga, according to certain Brahmanical interpretations and texts cited.

- Kshatriya: Refers to a Varna, traditionally associated with rulers, warriors, and administrators. The article discusses the historical debate and denial by certain Brahmanical texts regarding the existence of true Kshatriyas in Kaliyuga.

- Vaishya: Refers to a Varna, traditionally associated with merchants, traders, and farmers. The article discusses the historical debate and denial by certain Brahmanical texts regarding the existence of true Vaishyas in Kaliyuga and their legal struggle for Vedic rites.

- Dvija: Means “twice-born,” referring to the first three varnas (Brahmin, Kshatriya, Vaishya) who traditionally undergo the Upanayana (sacred thread ceremony) and are considered eligible for Vedic studies and rites.

- Vratya: A term mentioned in Manusmriti and used in the context of Shivaji’s coronation. It refers to a Dvija whose Upanayana ceremony was not performed, resulting in a degraded status.

- Vedic Rites: Religious ceremonies and rituals prescribed in the Vedas, traditionally performed by and for the Dvija varnas. The article discusses the denial of these rites to Vaishyas and Shivaji Maharaj.

- Shrimad Bhagavatam: One of the major Puranas, also known as Bhagavatam or Bhagavat Mahapurana. The article cites its narrative supporting the classification of kings after Mahapadma Nanda as Shudra.

- Mahabharata: A major Indian epic poem. The article cites its account of Parashurama’s annihilation of Kshatriyas.

Conclusion: Re-examining Historical Narratives on Caste Status

The historical evidence presented in this article, drawn from scriptures like the Vishnu Purana, Shrimad Bhagavatam, Mahabharata, and Manusmriti, as well as legal records from British India, reveals a complex and contested history of caste classification. It suggests that certain Brahmanical interpretations actively classified powerful groups, including Rajputs, Marathas like Shivaji, and Vaishyas, as Shudra in Kaliyuga, based on theories like the complete annihilation of Kshatriyas and Vaishyas by figures like Parashurama or Mahapadma Nanda. These classifications were not merely theoretical but had real-world consequences, leading to the denial of Vedic rites and becoming central to legal battles over status and inheritance in British courts.

The court cases of the Vaishyas and the Rajput inheritance dispute demonstrate how these scriptural interpretations were invoked in legal settings and how they were challenged. While the Vaishyas’ attempt to gain legal recognition for their right to Vedic rites failed in the Privy Council in 1845, the 1857 ruling in the Rajput case, which rejected the Parashurama annihilation theory as a basis for legal claims, marked a setback for the Brahmanical assertion that Brahmins were the sole surviving Dvija class in Kaliyuga.

The experience of Shivaji Maharaj further illustrates the lengths powerful rulers had to go to achieve formal recognition as Kshatriya, relying on adapted theories like the Vratya concept, and how Brahmanical authorities could revoke such recognition within generations. These historical accounts underscore the dynamic and often contentious nature of caste identity and historical caste status throughout history, highlighting the need to examine historical narratives with rigorous scrutiny and factual evidence.

What can you do?

To gain a deeper understanding of these historical realities, it is crucial to:

- Seek out and study historical documents and texts from various perspectives.

- Critically analyze claims about caste and history, demanding factual evidence and references.

- Understand the historical context in which scriptures and social norms were interpreted and applied.

- Use historical facts and authenticated references to counter misinformation and biased narratives about India’s past.

Read more about casteism in Indian Schools!!

Find out more about casteism in Indian Prisons!!

Do you disagree with this article? If you have strong evidence to back up your claims, we invite you to join our live debates every Sunday, Tuesday, and Thursday on YouTube. Let’s engage in a respectful, evidence-based discussion to uncover the truth. Watch the latest debate on this topic below and share your perspective!