Introduction: Questioning a Popular Narrative

The image of a bald man with a topknot, often portrayed as a great scholar and strategist who allegedly wrote Kautilya Arthashastra, is widely promoted in popular culture. People associate him with the name Chanakya or Kautilya and credit him with vast wisdom and the rise of the Mauryan Empire. Quotations attributed to him circulate widely, influencing public perception of ancient Indian knowledge and statecraft. However, a critical examination of history questions the authenticity of the Arthashastra and suggests that this widely accepted narrative may be a relatively recent construction, possibly dating back only within the last century or so. All the references used in the article are from the book – “Arthasastra Of Kautilya & Chanakya Sutra Vachaspati Gairola Chowkambha”

For centuries, when India was under foreign rule, people did not widely know or promote such figures or texts in the manner we see today. The sudden emergence and popularization of this narrative after independence raises questions about its historical authenticity and the motivations behind its promotion.

Table of Contents:

- A History of Fabrication: Motives Behind Creating a False Narrative

- The Maurya Empire: A Hidden History Unearthed

- Deciphering the Past: Language and Script

- The Invention of Kautilya: From Play to Historical Figure

- The Forgery of the Arthashastra: Questioning Authenticity and Origins

- Scholarly Scrutiny: Foreign Experts Challenge Authenticity

- Contradictions and Absurdities: What the Arthashastra Actually Says

- Conclusion: Questioning the Established Narrative

- What can you do?

- Disclaimer: Understanding Key Terms

A History of Fabrication: Motives Behind Creating a False Narrative

Those who fabricate history often lack genuine evidence for their claims. We can compare this act of falsification to a ‘thief’ attempting to tell their history without proof. In the context of Indian history, some argue that people constructed a fabricated narrative for two primary purposes: to seize control of India’s resources and wealth, and to claim the achievements of others while portraying the native population as intellectually inferior and in need of guidance.

One method they employed involved showing perceived dominance by claiming intellectual superiority. The narrative suggests, “we are wise and clever; you must take knowledge from us to progress; otherwise, you are foolish.”

Suppressing Maurya and Buddhist Heritage

Historical excavations revealed a rich past, particularly concerning the Maurya Empire, which was closely linked with Buddhism and Ajivika philosophy. Unearthed evidence contradicted the narrative that certain groups were attempting to establish. Because this history did not align with their desired portrayal, people made efforts to hide, suppress, or distort it entirely.

Claiming Achievements of Others

Another tactic involved co-opting the accomplishments of historical figures. For example, some claim that to diminish the achievements of Shivaji Maharaj, people falsely presented a Brahmin named Ramdas as his guru. This claim was reportedly challenged in court and found to be fabricated, demonstrating a pattern of attempting to attach a Brahmin figure to the success of prominent non-Brahmin historical personalities. This suggests a deliberate attempt to present Brahmins as essential enablers of greatness.

Controlling Resources

Parallel to claiming intellectual and historical credit, people made a systematic effort to gain control over India’s resources. By portraying themselves as the most clever and capable, they justified their position and control, framing others as incapable or foolish (‘Shudra’ – used here in a discriminatory context) who needed guidance or rule.

The Maurya Empire: A Hidden History Unearthed

When archaeological excavations began, particularly by the British, people discovered significant findings related to the Maurya Empire. These included inscriptions and pillars from Emperor Ashoka. Such discoveries were problematic for those who had suppressed this history because they revealed a flourishing civilization with its own language, script, and philosophical underpinnings, primarily Buddhist and Ajivika.

Prior to these discoveries, people propagated a prevalent narrative that India had no significant history before certain periods or that everything ancient belonged to a specific group’s tradition. The Maurya findings challenged this, necessitating a new strategy to either suppress or reinterpret the evidence.

Deciphering the Past: Language and Script

For a long time, people widely propagated a claim that Sanskrit was the oldest language of India. However, this claim faced challenges as historical evidence emerged.

The Myth of Sanskrit’s Primacy

During attempts to understand ancient inscriptions, particularly those from the Gupta period (read in the 1810s), people interpreted them through the lens of Sanskrit. A prevailing belief, influenced by certain groups, held that Sanskrit was the ancient language of India, leading to attempts to read all old scripts as Sanskrit.

James Prinsep’s Breakthrough

This changed significantly in 1837 when James Prinsep successfully deciphered the Brahmi script. His work revealed that the language of the Ashokan inscriptions was not Sanskrit, but Pali-Prakrit. This discovery fundamentally challenged the notion that Sanskrit was the oldest or primary ancient language across India, as people found Ashoka’s pillars across the subcontinent.

This finding caused significant discomfort for those who had built a narrative around Sanskrit’s antiquity and prominence, as it exposed their claims as false.

Misinterpreting Ashokan Edicts (“Beloved of God”)

Even after the decipherment, some groups attempted to control the interpretation of the Ashokan inscriptions. For instance, people interpreted the title “Devanampiya Piyadassi” used by Ashoka as “Beloved of God.” It is argued that this translation was influenced by certain groups who, understanding that ‘Deva’ in the Buddhist context referred to humans, deliberately mistranslated it to suggest a connection to a singular ‘God’ or deity as understood in their own tradition. This aimed to obscure the Buddhist nature of the edicts and attribute them to a different religious framework. This misinterpretation persisted for a time in early translations.

People see this effort as part of a broader strategy to Hinduize or Brahmanize historical figures and texts that originated from non-Brahminical traditions like Buddhism and Ajivika. People accuse them of introducing concepts like ईश्वर (Ishvara – God) and आत्मा (Atma – Soul), which were not central or even present in early Indian philosophical systems like Buddhism or Ajivika, to assimilate these traditions into a later framework.

The Invention of Kautilya: From Play to Historical Figure

With archaeological and linguistic evidence exposing historical facts, people devised a new strategy. This involved creating a figure that could explain the greatness of the Mauryan Empire while centring the narrative around a specific, preferred character.

Mudrarakshasa: Introducing the Character

People link the creation of the character of Kautilya to a Sanskrit play titled Mudrarakshasa, attributed to Vishakhadatta (some claim the 6th to 10th century CE, but this dating is questioned). This play features Kautilya as a key advisor to Chandragupta Maurya.

For decades after the decipherment of Brahmi script in 1837, people likely deliberated on how to counter the findings. This play only gained prominence much later. Bharatendu Harishchandra reportedly translated Mudrarakshasa in the 1870s (he lived 1850-1885), bringing the character of Kautilya into wider discourse. This play, being a work of fiction, did not require historical evidence for its characters or plot.

Establishing the Guru-Disciple Narrative

People used the play as a basis to establish the narrative that Kautilya was Chandragupta Maurya’s guru. The idea was that Chandragupta’s success was not his own, but resulted from following the guidance of this exceptionally wise teacher. This echoes the pattern seen with the Shivaji-Ramdas claim, where people attribute the achievement of a historical figure to the influence of a Brahmin guru. This suggests a deliberate attempt to re-frame history.

Just as Shakespeare wrote plays, and we understand his works as fiction, Mudrarakshasa should also be seen as a play. However, some argue that people later used this fictional work as a basis to construct a historical figure.

The Forgery of the Arthashastra: Questioning Authenticity and Origins

With the character of Kautilya introduced through *Mudrarakshasa*, the next step was to provide him with a magnum opus – a work of profound knowledge and strategy that would solidify his image as a great scholar and advisor. This led to the emergence of the text known as the Arthashastra.

Shama Shastri’s Publication

The figure central to bringing the **Arthashastra** to light is **Shama Shastri**. It is claimed that after years of deliberation following the 1837 decipherment and the popularization of the Kautilya character, Shama Shastri published parts of the **Arthashastra** in 1905 in the *Indian Antiquary*. He published the complete text with alleged greater accuracy in 1909.

Through this publication, Shama Shastri attempted to establish three key points:

- Acharya Kautilya was indeed the minister (Amatya) of Chandragupta Maurya.

- The Arthashastra is a genuine work authored by Kautilya himself.

- The text published is the authentic original text of the Arthashastra.

People made these claims decades after scholars definitively identified the language and script of the Maurya period as Pali-Prakrit and Brahmi, and questions about the historical narrative were already arising.

Methods of Manuscript Fabrication

Shama Shastri may have fabricated the manuscript he presented. The method described resembles the alleged method used for the Vimana Shastra, another text whose authenticity and ancient origin people question. Subbaraya Shastri, who produced the Vimana Shastra in 1922 (after the Wright brothers’ flight in 1903), serves as an example of this alleged practice.

Picture this: Someone wants to invent a lost ancient text. They might write manuscripts on old paper or palm leaves, making them look aged. Then, they strategically place these documents in various locations across different regions. Afterwards, they claim to have received a divine message or dream revealing the location of these hidden manuscripts. They then ‘discover’ these documents, presenting them as ancient texts. This systematic creation and ‘discovery’ of manuscripts allowed them to present a text and claim its ancient origin, thus supporting the narrative of Kautilya’s existence and work. People suggest Shama Shastri used this method to produce the ‘ancient’ Arthashastra manuscript.

Scholarly Scrutiny: Foreign Experts Challenge Authenticity

Immediately after Shama Shastri published the Arthashastra, it faced significant skepticism from foreign scholars. They examined the text using critical tools, including linguistic and historical analysis. While some early scholars like V.A. Smith initially accepted Shama Shastri’s claims in his work Early History of India (1914 edition), this acceptance was not universal or lasting.

Early Doubt and Contradictions with Megasthenes

Foreign scholars began noticing significant discrepancies between the Arthashastra and accounts of the Maurya period by contemporaries like Megasthenes, the Greek ambassador to Chandragupta’s court. Otto Stein, in his comparative study Megasthenes and Kautilya, highlighted these contradictions. He noted that the society and statecraft described in the Arthashastra did not align with Megasthenes’ observations. For instance, Megasthenes’ account did not suggest the strict Varna system or many of the administrative details described in the Arthashastra, or if they existed, they were not in the form presented in the text.

Dr. Jolly Declares it a Forgery

One of the most direct challenges came from Dr. Jolly. In 1923, he published his book, Arthashastra of Kautilya, in the Panjab Sanskrit Series, Lahore. In the introduction to this book, Dr. Jolly argued that the Arthashastra was a forged text written in the 3rd century CE, not during the time of Chandragupta Maurya (late 4th century BCE). He concluded that its author, Kautilya, was a fictional state minister. He based this outright declaration of forgery on textual analysis, comparison with known historical facts, and linguistic considerations.\

Further Support from Winternitz and Keith

Dr. Moriz Winternitz, in his influential work History of Indian Literature (published in 1927), echoed and supported Dr. Jolly’s conclusions regarding the Arthashastra‘s authenticity and date. He dismissed counterarguments as mere objections.

Dr. Arthur Berriedale Keith further supported this view in a paper in the Sir Ashutosh Memorial Volume (1928). He categorically stated that people could not have composed the Arthashastra before 300 CE, reinforcing the argument that it was not a product of the Maurya era. He, too, considered the entire work an unauthentic composition from a later period.

Thus, soon after its publication, prominent Western scholars recognized significant issues with the Arthashastra’s authenticity and dating, classifying it as a later, unauthentic, or even forged text.

Contradictions and Absurdities: What the Arthashastra Actually Says

An examination of the contents of the Arthashastra, as presented in translations, reveals aspects that appear contradictory to the known history of the Maurya period and contain elements that seem irrational or designed to promote specific interests.

According to the Arthashastra the duties of different varnas (social classes):

- Brahmins: Studying, teaching, performing sacrifices, helping others perform sacrifices, giving and receiving donations.

- Kshatriyas: Studying, performing sacrifices, giving donations, living virtuously, protecting living beings.

- Vaishyas: Studying, performing sacrifices, giving donations, agriculture, cattle rearing, and trade.

- Shudras: Serving the upper varnas, agriculture, cattle rearing, and trade.

The text presents this detailed description of a rigid Varna system and associated duties as the ideal social order. However, accounts from the Maurya period, such as those by Megasthenes, do not describe Indian society in this manner. This discrepancy raises questions about whether such a rigid system was prevalent or codified in this way during Chandragupta’s reign.

Caste System and Varna Dharma

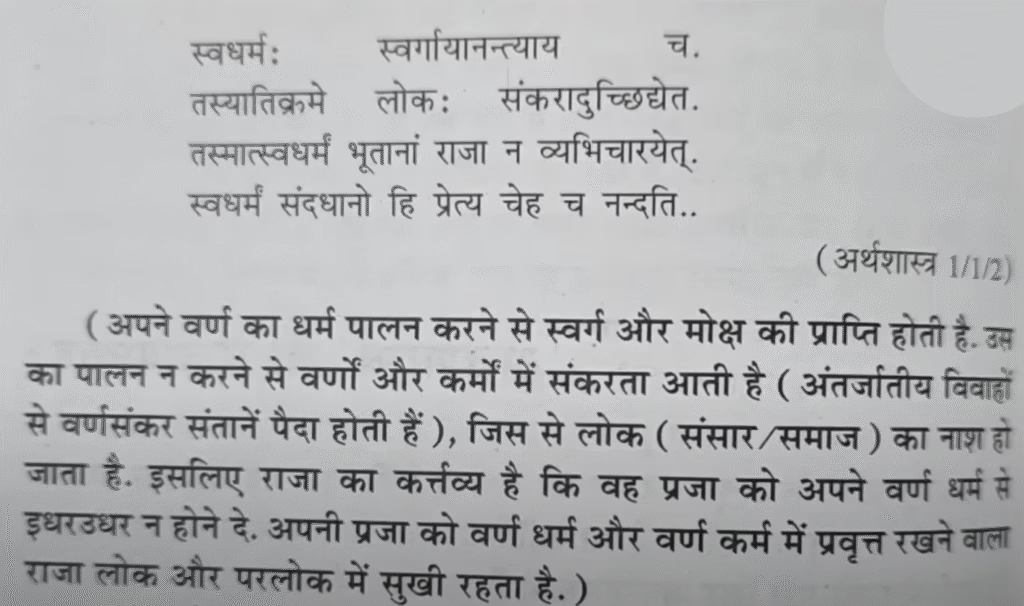

The text goes further, stating that adhering to one’s Varna Dharma leads to heaven and liberation (स्वर्ग और मोक्ष – Svarga aur Moksha). Conversely, it warns that not following these duties leads to “impurity” (संकरता – Sankarata) in varnas and actions.

Specifically, it claims that inter-caste marriages result in mixed-caste offspring (वर्णसंकर संतान – Varnasankar santan), which leads to the destruction of society (लोक संसार समाज का नाश). It declares that the king’s duty involves ensuring no one deviates from their Varna Dharma.

This instruction directly contradicts historical accounts. Chandragupta Maurya himself married a foreign woman (Helena, daughter of Seleucus I Nicator), which would be considered an inter-caste/inter-cultural marriage. If Chandragupta himself married outside the strict varna system described, could this text truly be his advisor’s work? A text advising against such unions and promoting a rigid Varna system seems unlikely to be the work of his actual advisor.

Superstition and Rituals

The Arthashastra includes bizarre and superstitious elements. For instance, it describes a ritual involving rubbing bamboo against a human bone to produce fire, taking this fire into the queen’s chambers (अन्तःपुर/रनिवास – Antahpura/Ranivas), and having a queen touch it.

It claims that performing this ritual would make the fire harmless and prevent any other fire from burning there. It also mentions using ash from a lightning-struck tree mixed with clay and Datura juice as a paste for walls to prevent fires. These descriptions sound like witchcraft or folk remedies, not the pragmatic statecraft expected from a genius strategist, and appear nonsensical.

Brahmin Dominance and King’s Duty

The text places significant emphasis on the role and authority of Brahmins. It instructs the king to appoint a Brahmin priest (पुरोहित – Purohit) knowledgeable in Vedas, astrology, rituals, and capable of counteracting divine and human calamities using measures specified in the Atharvaveda (often associated with rituals and incantations, including टोना-टोटका – Tone-Totka, loosely translated as witchcraft/sorcery). The king is told that he should follow this priest like a son follows a father or a servant follows a master.

The text asserts that a king supported by a Brahmin priest, secured by capable ministers, and performing rituals as described in scriptures, can achieve success even without fighting. This perspective suggests that victory comes through religious rituals and obedience to priests, rather than military strategy and effective governance. Such advice, it is argued, explains why rulers who followed this path often suffered defeats, contrasting with the successful, independent approach of rulers like the Mauryas who people associated with Buddhism and Ajivika traditions.

Brahmins Leeway Demanded in Arthshastra

Furthermore, the text mandates that the king must donate tax-free land to Brahmin priests, teachers, and scholars and never reclaim it. It also suggests giving land designated for forest or pasture to Brahmins for studying the Vedas and performing sacrifices. This instruction appears designed to serve the specific interest of accumulating wealth and land for a particular group, rather than outlining impartial state policy for the benefit of the entire kingdom.

Finally, the Arthashastra states that if a Brahmin commits a grave offence, people should not kill them, as killing a Brahmin is prohibited. Instead, they should face imprisonment or exile. This rule grants a specific community immunity from the most severe punishment, regardless of the crime, suggesting a clear bias within the legal framework described.

These examples from the text suggest that the Arthashastra, as Shama Shastri presented it, may not be an authentic work from the Maurya period. Instead, it could be a later composition reflecting the social norms, beliefs (including superstition), and power structures that someone wished to promote or justify, possibly from a much later era. The debate around the authenticity of the Arthashastra remains crucial for understanding its place in history.

Conclusion: Questioning the Established Narrative

Based on the historical evidence, scholarly critiques from the early 20th century onwards, and the contents of the text itself, a strong argument suggests that the figure of Kautilya/Chanakya as the author of the Arthashastra, and the text’s dating to the Maurya period, represents a narrative constructed significantly later than the time it purports to represent. Prominent scholars identified the text as a later, potentially unauthentic, or forged work shortly after its publication, casting doubt on the authenticity of the Arthashastra.

The popular image and associated wisdom attributed to Chanakya appear to be part of a deliberate effort to reinterpret history, suppress inconvenient truths about earlier periods like the Buddhist Maurya Empire, and establish a narrative that supports a specific worldview and social structure.

What can you do?

Understanding this perspective on the historical figure of Chanakya and the **Arthashastra** encourages a critical approach to widely accepted historical narratives. To form your own informed opinion:

- Seek Evidence: Always question the sources and evidence presented for historical claims. Look for corroborating evidence from diverse sources, including archaeological findings, inscriptions, and accounts from contemporary foreign observers.

- Read Critically: Approach texts like the Arthashastra with a critical eye. Consider its contents in light of what is known about the historical period it claims to represent, and analyse any apparent contradictions or biases within the text itself. Evaluate the claims about the authenticity of the Arthashastra based on the evidence presented by various scholars.

- Explore Alternative Histories: Learn about the history of the Maurya Empire, Buddhism, Ajivika philosophy, and other ancient Indian traditions from scholarly and evidence-based sources. Explore the works of historians and researchers who have questioned the conventional narratives.

- Engage in Informed Discussion: Share your understanding and encourage others to question popular narratives and seek deeper historical knowledge based on evidence, fostering a culture of scientific temper and rational inquiry.

Disclaimer: Understanding Key Terms

Below is a list of common terms used in this article and their meaning in this context:

- Shudra: The lowest of the four varnas in the traditional Hindu social hierarchy.

- Brahmin: The highest varna, traditionally associated with priestly duties, teaching, and knowledge.

- Pali: An ancient Middle Indo-Aryan language, often associated with early Buddhist scriptures.

- Prakrit: A group of ancient and medieval Indo-Aryan languages, spoken in the Indian subcontinent. Pali is considered a form of Prakrit. Ashoka’s inscriptions were primarily in various forms of Prakrit using the Brahmi script.

- Brahmi: An ancient Indian script, the ancestor of many South Asian scripts. James Prinsep deciphered it, and people used it in Ashoka’s inscriptions.

- Ajivika: An ancient Indian ascetic and philosophical movement, contemporary to early Buddhism and Jainism. People reportedly inclined Chandragupta and Bindusara towards this philosophy.

- Arthashastra: A treatise on statecraft, economics, and military strategy, traditionally attributed to Kautilya or Chanakya. The article discusses the debate around its authenticity and dating.

- Mudrarakshasa: A Sanskrit play by Vishakhadatta, featuring Kautilya as a key character. Some argue it was the source for creating the character’s popular image.

- Manuscript: A book, document, or piece of music written by hand rather than typed or printed. The article discusses the origins and potential fabrication of the Arthashastra manuscript.

- Svarga aur Moksha (स्वर्ग और मोक्ष): Heaven and liberation; spiritual goals mentioned in certain texts.

- Sankarata (संकरता): Impurity or confusion, particularly related to the mixing of Varnas.

- Varnasankar santan (वर्णसंकर संतान): Offspring resulting from inter-caste marriages, considered undesirable in texts promoting the Varna system.

- Antahpura/Ranivas (अन्तःपुर/रनिवास): The inner chambers or women’s quarters of a palace.

- Tone-Totka (टोना-टोटका): Rituals or incantations, sometimes associated with sorcery or witchcraft.

Read more about the True history of Ayodhya!!

Find out more about the True History of Mathura!!

Do you disagree with this article? If you have strong evidence to back up your claims, we invite you to join our live debates every Sunday, Tuesday, and Thursday on YouTube. Let’s engage in a respectful, evidence-based discussion to uncover the truth. Watch the latest debate on this topic below and share your perspective!

[…] BibliographyHere is a comprehensive bibliography of key academic and historical sources used to analyze the fictionality and mythologization of Chanakya/Kautilya, his alleged authorship of the Arthashastra, and relevant historiographical debates[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13]:***Primary Sources and Contemporary Accounts– Megasthenes. *Indica*. (As cited and discussed in comparative studies)[14][15]– Ashoka. *Edicts of Ashoka*. (Inscriptions)[16][17]– Chandragupta Maurya. (Referenced in Greek and Buddhist/Jain sources)[18][19]– Vishakhadatta. *Mudrarakshasa* (Sanskrit play, c. 6th–10th century CE)[3][20]***The Arthashastra: Critical Editions and Translations– Kautilya. *Arthashastra*. Ed. R. Shamashastry (1909, 1915 editions, Mysore Oriental Library)[21][22]– R.P. Kangle. *The Kautilya Arthashastra, Part I: Critical Edition with a Glossary*, Part II: Translation with Commentary* (1960)[9][12]***Foundational Scholarly Analysis and Criticism– Stein, Otto. *Megasthenes und Kautilya: Eine kritische Studie* (1921)[13]– Jolly, Julius. Various articles (1923) challenging Arthashastra’s authenticity and historicity[1][2]– Winternitz, Moriz. *Geschichte der Indischen Literatur* (1927)– Keith, Arthur Berriedale. “Kautilya and the Arthashastra.” (1928)– Trautmann, Thomas. *Kautilya and the Arthashastra* (1971, updated 2025: Cambridge University Press)[5][23]– Olivelle, Patrick. *King, Governance, and Law in Ancient India: Kautilya’s Arthashastra* (2013)– McClish, Mark. *The Historical Foundations of Kautilya’s Arthashastra: Politics, Ethics, Economics* (2019)***Recent Studies, Debates, and Historiography– “Unraveling the Arthashastra Authenticity Myth,” Caste Free India (2025)[1]– “The Authoring and composition of Arthashastra.” CT William (2025)[24]– Alexandrowicz, C.H. “India and the Kautilyan Moment,” Asian Journal of International Law (2025)[25]– “The Kautilya Conundrum,” schandillia.com (2024)[26]***Comparative Historical and Social Analysis– “Historical Sources of Mauryan Empire: Indica, Arthashastra…” TarunIAS (2025)[27]– “Mauryan Dynasty: Ancient Times of Indian History,” IJCRT (2021)[28]– Devdutt Pattanaik, “How Jains Described Chanakya and Chandra Gupta Maurya” (2023)[29]– “Jain Traditions on Chanakya and Chandragupta,” Prasun123 Blog (2020)[30]***General References– Wikipedia articles on Chanakya, Arthashastra, Chandragupta Maurya, Mauryan Empire, and Ashokan Edicts[3][7][31][17][18]– Britannica, “Artha-shastra | Indian Economics, Statecraft, Politics” (2025)[32]– Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, “One Hundred Years of Kautilya’s Arthashastra”[33]– “A tribute to Shamashastry,” Tamilbrahmins.wordpress.com (2012)[34]***Further Reading– Thomas Trautmann, “A Review of Trautmann’s Arthashastra,” Alex Thomas blog (2016)[35]– Patrick Olivelle (editor), *The Arthaśāstra: Selections and Commentary* (Oxford and Penguin editions)– R.S. Sharma, “Material Culture and Social Formations in Ancient India”*****Note:** All references were accessed between 2023 and 2025, representing both older foundational scholarship and newer contributions to the debate.Citations:[1] Unraveling the Arthashastra Authenticity Myth – Caste Free India https://castefreeindia.com/unraveling-the-arthashastra-authenticity-myth/ […]